I often take a train to New Haven nowadays, and since I find trains very relaxing I invariably feel drowsy as we pull out of Grand Central Station.

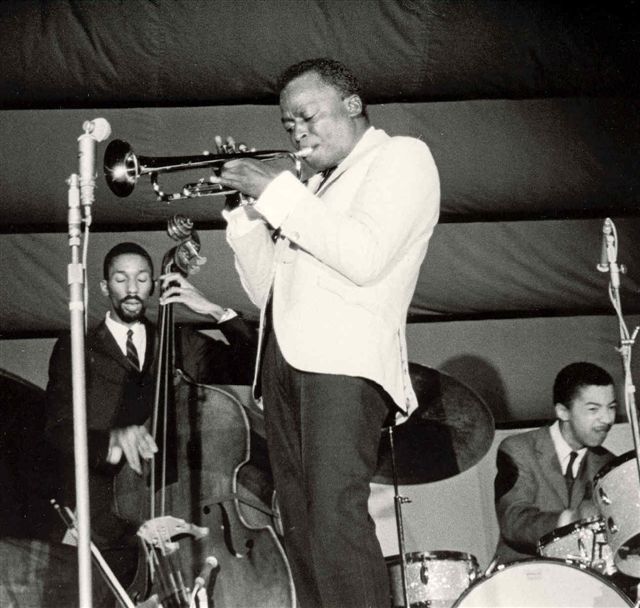

Nonetheless, I always awaken as we chug by Woodlawn Cemetery. Miles Davis lies within and I fantasize that the “coolest man in the universe” gently rouses me with a toot of his golden horn.

Truth be told though, I feel very at home around graveyards. And why wouldn’t I? My grandfather, Thomas Hughes, was a monumental sculptor.

He was a quiet man who had left school at 14 to be apprenticed to his father. When he was 18, Thomas left his native Carlow with a horse and car, a load of limestone, and drove the fifty miles to Wexford town where he set up shop.

Life was far from easy, but he married, raised a large family, and prospered. Some years after my grandmother died, I moved in “to keep him company.”

Parents would never part with their darlings nowadays, but Ireland was a different country back then.

Gorey, County Wexford.

I probably still have limestone dust in my lungs for I spent much time in his yard near Wexford Quay. On Sunday afternoons, however, we usually took a leisurely drive through the countryside.

We would always stop at a graveyard, and he would potter around until some statue or headstone caught his eye, and there he would stand riveted, for what seemed like hours.

It took many years before I realized that he was either figuring out how to create or improve on such a work. For he was an artist, though he had never taken a lesson. Whatever he knew he’d learned through observation and hands-on experience.

His allies were the traveling people who loved sumptuous memorials. He would stand in his drafty office surrounded by heartbroken families as they pored over pictures of ornate headstones and statues.

They always paid cash up front, but he willingly offered big discounts for the chance to carve something original.

When I was 15, I began working for him during summer vacations. Patron Days in cemeteries were held all through those weekends. Families wished their ancestral graves to be brought up-to-date and spruced to their best, with the names of recently deceased added, old headstones cleaned, and new ones erected.

Miles Davis performing in 1963.

My job was to mix cement, scour stones and kerbing, and make the tea. There was little rush, you could dream as you toiled; but most of all I loved the peace and quiet that came with the terrain.

I also loved my workmates. Tom Fortune was from “out the country,” while John Redmond was a townie from nearby Monck Street. Between them they had accrued much native wisdom, and when pushed would share it.

All hell, however, broke loose the following morning for we had raised the headstone over the wrong grave, and to add insult to injury there had been bad blood of long standing between the two aggrieved families.

They were kind men who treated me as an adult, and I learned much from them about life, including how to maneuver a stick-shift truck. They were both at ease with the world and content with their occupation, for it saved them from the scourge of loneliness in emigrant London.

One memory still causes a chuckle. We were sent to erect a headstone in a small overgrown graveyard up near Gorey. The person who had ordered the job failed to show.

However, there was a fairly recently dug grave situated in the general area where we had been instructed to put up the headstone.

It was a routine job and we took our time, savoring the lovely August day. In the late afternoon we departed for home with the contented feeling of another job well done.

All hell, however, broke loose the following morning for we had raised the headstone over the wrong grave, and to add insult to injury there had been bad blood of long standing between the two aggrieved families.

We rushed back out into a local cold war, and with much difficulty dislodged the headstone and kerbing. We then cleaned up the ravaged grave area as best we could under the stony gaze of the offended family.

The sun was going down as we erected the headstone over the proper grave, amid the muttered taunts and criticisms of the other hostile clan.

It made for a long, difficult day, but such is life, death, and bad blood in a country graveyard. We could have used a couple of soothing toots from Miles Davis’s golden horn.