Back in 1969 when Bernadette Devlin outraged conservative Irish-America with her socialist views and support for African-American civil rights, did she inspire memories of three women with similar convictions?

I often think of them as the she-trinity of Irish-American radicalism: Mother Jones, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (The Rebel Girl), and Margaret Sanger.

Though allies and sometimes friends, each ploughed their own furrow. Two things did unite them – a bedrock belief in the dignity of humanity, and membership of the Wobblies (International Workers of the World).

Mary G. Harris (Jones) emigrated from Cork to Canada in her early teens. She became a schoolteacher and took up a position in Michigan, but chafed under religious authority and quit.

In Memphis she married George Jones, an ironworker and union official, and raised a family with him.

We would probably have heard no more of her if yellow fever hadn’t struck Memphis, killing Mr. Jones and their four young children.

Never speaking about her loss, Mary moved to Chicago where she started a successful dressmaking firm. But in 1871 the Great Fire destroyed much of her business.

This galvanized her and she threw herself into union activities; because of her militancy and courage when facing down bosses, militias, and strikebreaking thugs, she became known as “the most dangerous woman in America.”

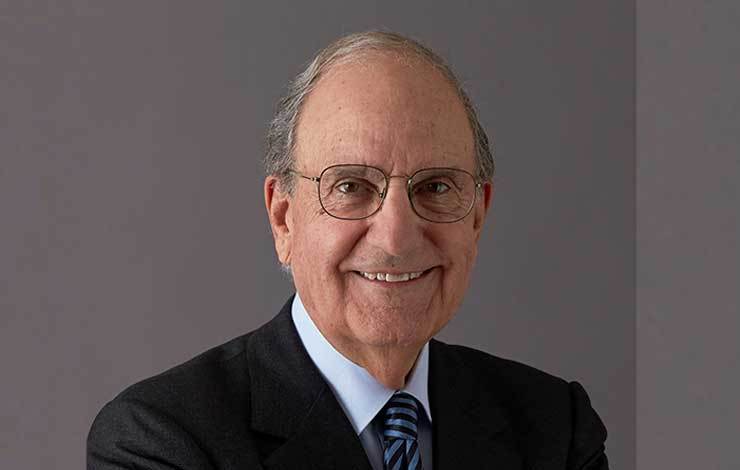

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.

When Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was taken as a child to one of Mother Jones’ rallies she was overcome by the power and presence of this diminutive Cork woman.

Flynn was born in Concord, New Hampshire to an Irish-speaking mother from County Galway and an Irish-American father with Mayo roots.

They moved to the South Bronx in 1900, and when she was fifteen the Rebel Girl gave her first public speech on “What Socialism Will Do For Women.”

She would become one of the greatest orators of her time and a tireless fighter for workers rights and freedom of expression.

A close friend of both James Connolly and Big Jim Larkin, she rallied thousands of immigrant workers and their sweatshop-employed children in Lawrence, Massachusetts during the successful Bread and Roses campaign for better wages and conditions.

Margaret Sanger.

Margaret Louise Higgins (Sanger) was born in Corning, New York in 1879 to Irish immigrant parents. Not unusual for those days, her mother, Anne Purcell-Higgins, conceived 18 times, with only 11 children surviving before she died at age 49.

Margaret became a nurse practitioner at White Plains Hospital. Though she suffered from recurring tuberculosis she worked as a visiting nurse in Lower East Side slums and became active in the Socialist Party and the Wobblies.

Along with Gurley Flynn during the Bread and Roses campaign, she organized the evacuation of immigrant children from Lawrence to homes in New York and Philadelphia where they would be fed and cared for by sympathetic families.

On Feb. 24th, 1912, at Lawrence railway station, mothers and children were bludgeoned by police and state militia. This led to a national outcry and the eventual settlement of the strike on favorable terms to the workers.

Inspired by her mother’s experience Margaret Sanger had great sympathy for women who underwent frequent childbirth that often led to miscarriage.

The Comstock Act of 1873 and other anti-obscenity laws forbade access to contraceptive information, and Sanger realized that fundamental social change could never occur until women were freed from the burden of unwanted pregnancies.

In 1914 she published "The Woman Rebel," a newsletter that promoted contraception, and challenged the federal anti-obscenity laws that forbade the spreading of information about “birth control,” a term she and her associates coined.

She was indicted and, rather than risk jail, she fled the U.S. for Britain.

She returned unrepentant in 1916 and, with her sister Ethel Byrne, opened the first birth control clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn. They were arrested for breaking a law that forbade the distribution of contraceptives.

While imprisoned, Byrne went on hunger strike and was the first American woman to be force-fed. There would be many battles before contraception was finally legalized in the U.S. through the 1965 Griswold v Connecticut Supreme Court Case. Her work finally completed, Margaret Louise Higgins Sanger died a year later.

The she-trinity is largely forgotten now, at a time when immigrant children are still being unlawfully employed, and reproductive rights are again under threat in the Home of the Brave and the Land of the Free.