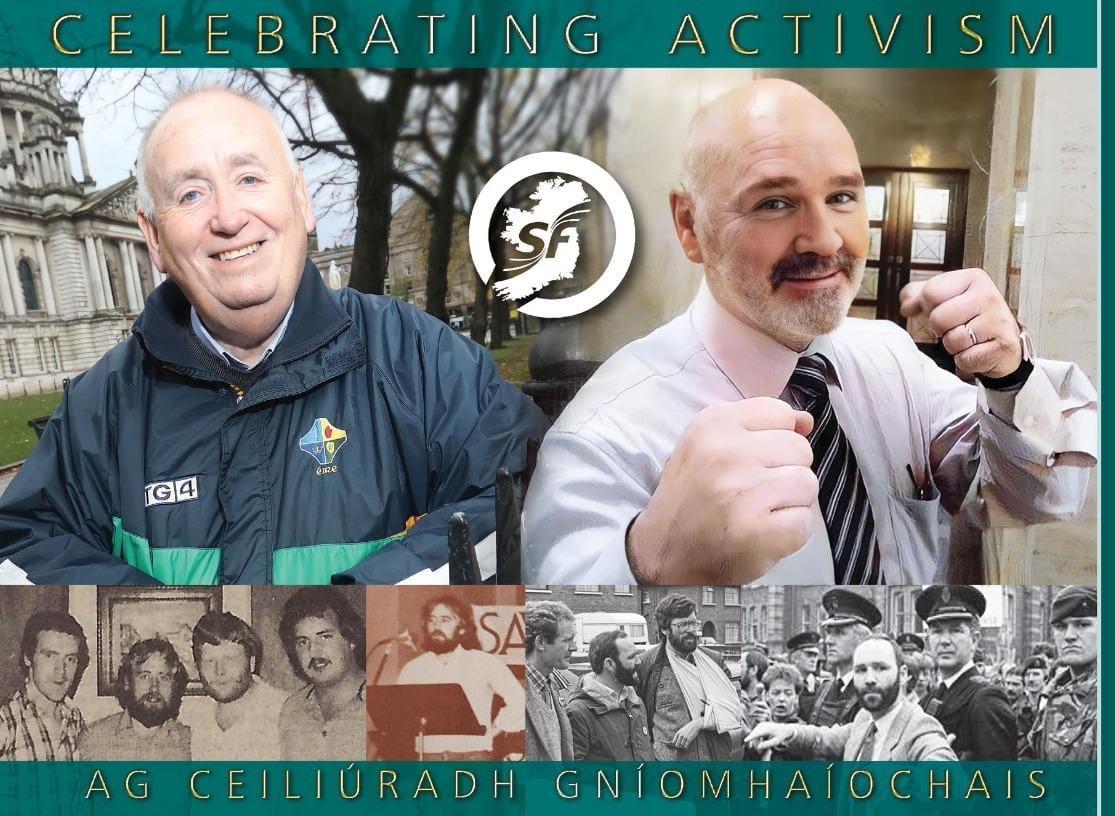

Republicans don’t say thank you often enough to each other. Fra McCann and Alex Maskey are fifty year activists. That is they have both been involved in the struggle for over fifty years.

The two of them stepped down from the Assembly two years ago. Fra was replaced by Aisling Reilly and Alex by Danny Baker. Alex still remains the Ceann Comhairle – Speaker of the Assembly – until such times as the DUP agree to elect a new Speaker.

Last Friday evening several hundred family, friends and comrades of both men came together to celebrate their lives of activism. They were also interviewed by Joe Austin about their experience of community activism, struggle, imprisonment and elected politics.

There was a big team of McCanns and Maskeys, siblings, wives, children and grandchildren, in the hall to hear Jeanette McCann and Liz Maskey equally honored for putting up with their husbands.

I fondly remembered Fra’s mother and father Ruby and Patsy, and his brother Paul, and all the McCanns, and Alex’s parents Alec and Theresa and all the Maskeys.

Fra and Alex’s roles are rooted in this family context, and in the communal and generational context of our struggle. Their parents and grandparents suffered under the weight of partition, under unionist rule and British rule, and the poverty and discrimination inflicted upon the working class communities that most of us come from.

No doubt their parents and grandparents resented the way they were treated. No doubt they railed against this, or protested at different times against the status quo. But such protestations failed to bring about any real change.

Alex and Fra grew up in the 60s. That was a time when change was in the air. The civil rights campaign was on the march. The unionist regime and its allies were attacking it. Then came the Battle of the Bogside and the eviction of families in North Belfast, and the widespread pogroms of August '69.

Instinctively, Fra and Alex and Liz - Janette was too young - resisted oppression. They were part of a community uprising which opposed the aggression of the RUC, the B Specials, the unionist murder gangs and the British Army. Belfast republicans and others wrapped their arms around those in need; those arrested, tortured, beaten, burned out of their homes and forced to flee as refugees.

A newly empowered community made a stand. Many moved from passive acquiescence to active resistance. Fra and Alex chose to be activists.

For our two comrades and their families the struggle has brought difficult choices, years of imprisonment, heartbreak, danger and threats, the deaths of close friends and more than one close shave with death for each of them. It has also brought a determination, a resolve, to make things better for those who would come after them.

In 1969, and into the early 70s, they were on the barricades. Juvenile rebels with a cause. Fifty years later they are still rebels, a little geriatric now, but rebels nonetheless and still positive through all the twists and turns of struggle and life.

Alex and Liz – an activist in her own right, and the first woman to be interned – faced many challenges inside and outside of the prisons. Their friend Alan Lundy was killed in their living room. On another occasion Alex was gravely wounded and quietly, courageously, carries those scars today.

Fra too has endured much. On the run. Beatings. Internment. Desi Macken dressed in a cowboy suit and telling tall tales about him. Digging tunnels in Long Kesh and crawling through the muck and the water. His friend and comrade Hugh Coney shot dead lying beside him. His brother killed. Later Fra became a blanketman in the notorious H Blocks of Long Kesh.

During the hunger strike campaigns Alex and Fra played exemplary roles, traveling, organizing, planning, and winning support for the blanket men and the Armagh women. The hunger strikes were a watershed moment in modern Irish history, but especially for the republican struggle.

In the 1980s we developed new strategies and new tactics. And Fra and Alex were at the heart of this.

Their generation’s gift to today’s generation of activists is a mechanism to achieve Irish Unity. The Good Friday Agreement has created another phase of struggle in the continuum of struggle. Alex and Fra, and many more, helped to bring this about.

Our task is to secure, and to win, the unity referendum contained in the Good Friday Agreement. Of course, it won’t be easy. Struggle rarely is. But never forget what we were told over the decades by the great and the good. They told us time and again that many of the changes demanded by us would be impossible.

But look back over the fifty years of Fra and Alex’s activism and count all the impossible achievements of that time. Think of the many times we were told we would fail.

So republicans can face the future with confidence, not least because of the activism of patriots like Fra and Alex.

They epitomize the spirit that Bobby Sands wrote of in the last entry of his prison diary: “If they aren’t able to destroy the desire for freedom, they won’t break you. They won’t break me because the desire for freedom, and the freedom of the Irish people, is in my heart. The day will dawn when all the people of Ireland will have the desire for freedom to show. It is then we’ll see the rising of the moon.”

Thank you Bobby. Thank you Fra. Go raibh maith agat Alex. Thank you also Liz and Janette.

PRISON BOOK BAN LIFTED

Last week I wrote a piece about books and the prison system here. That literary ramble through our penal institutions was triggered by news that some books by republicans are banned from the prisons here. Pat Sheehan MLA, a former prisoner and hunger striker, wrote to the prison authorities.

He said: “Twenty-five years after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement I find it incomprehensible that republican literature should still be censored in this way. I thought those days were long behind us. The Irish republican analysis of our history is as valid as any other, and attempts to censor that analysis only serve to indulge the view that the prison service is politically partisan.”

In response, Pat was told that an independent book review panel at Prison Service Headquarters was established some time ago "to ensure a decision to deny access to any publication by a prisoner could be independently reviewed. This allows a prisoner to appeal a decision and to request a review, and that has happened on a small number of occasions."

This included "No Greater Love." That book was reviewed by the panel and the original decision to deny access was overturned.

The Joe Cahill book is also to be reviewed and Pat has been advised that the review panel will "consider the current guidance on books to take into account such issues as historical context of the publication." This column will update you on the outcome of this undertaking. Joe Cahill would be pleased.

Brendan Behan (left) with Jackie Gleason in 1960.

BRENDAN BEHAN

February 9 marked the centenary of the birth of Brendan Behan. Behan was a hugely influential writer whose books were rooted in his working class experience and republicanism. His parents, Stephen Behan and Kathleen Kearney, were republicans. His mother’s brother, Peadar Ó Cearnaigh, was a veteran of the 1916 Rising and wrote "The Soldier’s Song" (Amhrán na bhFiann).

At the age of eight, Brendan joined the Fianna. Later he joined the IRA. In December 1939 he was dispatched to Liverpool to identify possible targets for the then bombing campaign. In his eagerness he brought with him explosives he had personally prepared. He was arrested. Because he was aged 16 Behan was sentenced to three years in a juvenile center. Almost twenty years later that story was told in "Borstal Boy." The book was banned in the South.

After returning to Ireland Brendan was imprisoned again between 1942-46. My Uncle Dominic was in Mountjoy with him. He told me Behan’s cell was filled with scraps of paper covered in Brendan’s writings. He was a fine poet, particularly in Irish.

He also was a chronic alcoholic, at times witty and entertaining, at other times aggressive and quarrelsome. By the time he died in March 1964 aged 41 he was widely recognized as one of the best Irish writers to have emerged in the 20th century. He was given a republican guard of honor at his funeral. I am a big fan of his writing and would recommend any of his books but "Borstal Boy" is especially worth a read.