Last week I attended an event in Parliament Buildings at Stormont, hosted by U.S. Special Economic Envoy Joe Kennedy III.

There was a panel discussion on the impact of the Good Friday Agreement which involved myself, former DUP leader Peter Robinson; former Alliance Assembly Speaker Eileen Bell; Lady Daphne Trimble, President of the Ulster Unionist Party, and former SDLP leader Mark Durkan.

First Minister designate Michelle O’Neill, DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson and UUP leader Doug Beattie were all present.

While we each brought our own narrative of that time to the conversation it was nonetheless a positive and forward looking engagement.

The day before, Jeffrey Donaldson said there would be no united Ireland in his lifetime and that a united Ireland cannot accommodate his Britishness. I disagree.

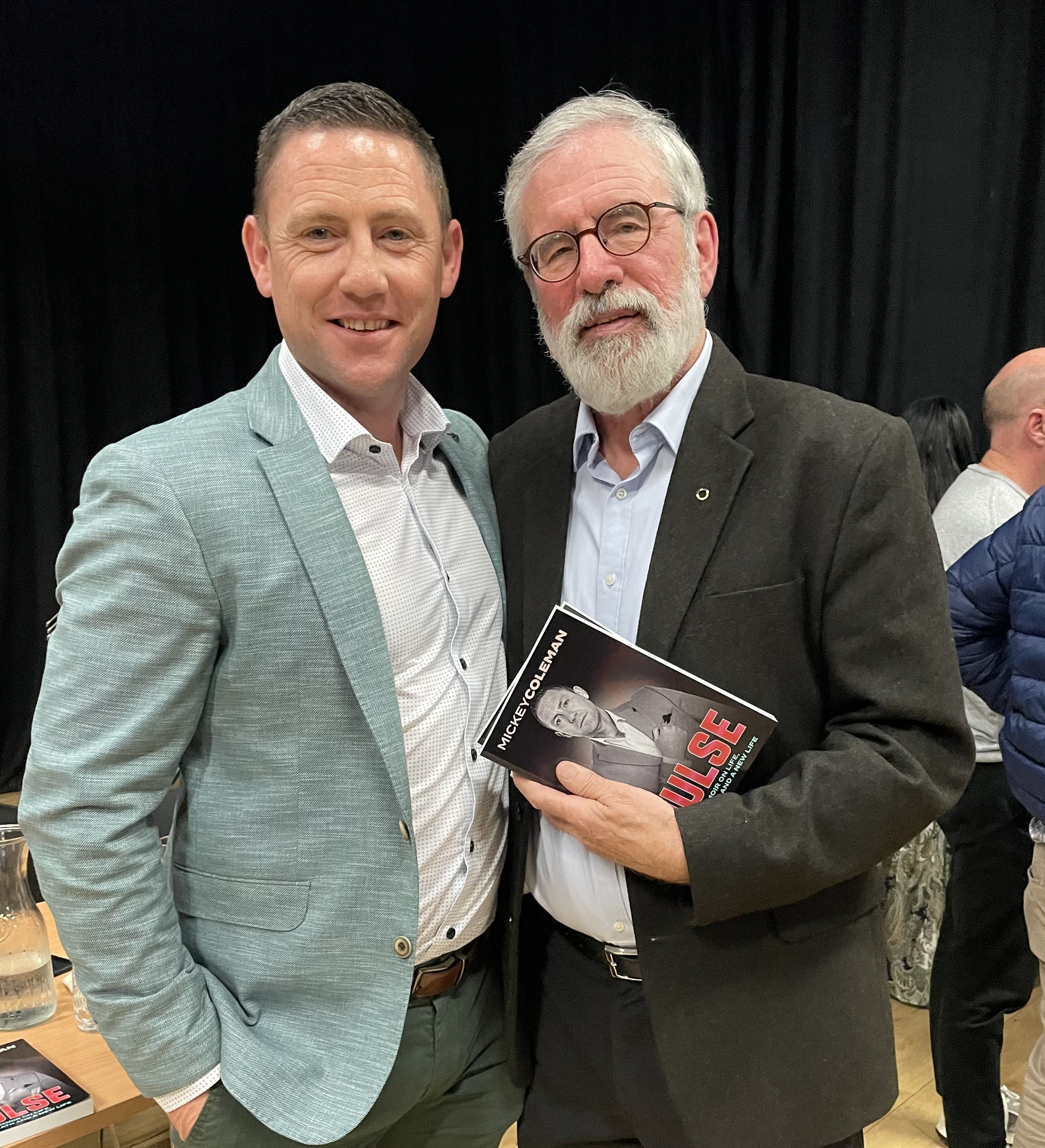

Mickey, Gerry and Peter Canavan.

The fact is that political and demographic changes in recent decades, a growing disillusionment with the unionist parties, the Brexit debacle and the growth of Sinn Féin, have contributed to increasing interest in Irish Unity. It is also important to recall that over 70% of people in the North and over 90% in the South voted in May 1998 for an Agreement that provides for a unity referendum and for a simple majority to determine the outcome. That provides the democratic basis for future constitutional change.

As for the British identity in a United Ireland? Those of us who favor Irish Unity have repeatedly emphasized our commitment to respect the British identity of our neighbors and to accommodate that identity and its traditions in a new and shared Ireland. We are also committed to the safeguards and guarantees, contained in the Good Friday Agreement, being carried through into that new Ireland.

That is not just a rhetorical commitment aimed at winning unionist support for, or acquiescence to, Irish Unity. It is rooted in the principles and beliefs of those - mainly Presbyterians - who embraced Republicanism in the 18th century.

The United Irish Society was founded in Belfast in October 1791. It was the first democratic movement in Ireland and took its inspiration from the American and French Revolutions of that time. They sought solidarity between people of all religious denominations, and political equality and Irish independence.

Theobald Wolfe Tone, who belonged to the Church of Ireland, embodied the new alliance between Protestants and Catholics. His writings remain relevant to this generation and this time.

The panel at the Stormont GFA discussion.

In facing up to a succession of economic and political crises then created by the English government Tone concluded that: “Ireland would never be either free, prosperous, or happy, until she was independent, and that independence was unattainable, whilst the connexion with England existed.”

To build a new society, Tone argued for a new relationship between the people of Ireland. He wrote: “The weight of English influence in the Government of this country is so great as to require a cordial union among all the people of Ireland, to maintain that balance which is essential to the preservation of our liberties and the extension of our commerce.”

As the momentum toward a unity referendum grows, and as more and more positive voices are being heard from the unionist/British section of our people, the objective of building a cordial union among the people of this island takes on a greater significance.

British governments are not to be trusted in protecting the rights of citizens or managing our economy. Agreements between unionist leaders and British governments have been consistently dumped by British prime ministers who, time and time again, have placed British self-interest above commitments given to unionists.

The future provides an opportunity to build a new relationship between the people who share this island. A new cordial union, founded on inclusion and reconciliation, on democratic agreements and respect. We are an island people in transition. A fundamental part of this transition must be a sustained effort to genuinely address the fears and concerns of northern unionists. As good neighbors we must explore with them what they mean by their sense of Britishness and how that sense of Britishness will be reflected in a new cordial union between the people of this island. This is the future.

CEASEFIRES NOW

News from the Middle East continues to numb and outrage and anger most people. But we cannot give up. We have a duty to the people of Palestine to stay focussed on the demands to stop the war, support humanitarian initiatives, start peace talks. The people of Israel and Palestine need the support of the international community. We are part of that community. Let us find ways to get our leaders to uphold international law. End the siege of Gaza. Free Palestine.

PULSE

Mickey Coleman, his wife Erin and their sons Micheál and Riordan, were in An Cultúrlann last week on Belfast’s Falls Road to launch Mickey’s new book "PULSE." Peter Canavan was there also, along with mé féin. I never thought I would be on a panel with Peter Canavan, one of my footballing heroes and all Ireland champion with Tyrone. Twice. But there we were telling yarns and sharing songs and funny stories. And a bunch of fine singers from Glassdrummond entertained us and moved everyone with their rendition of "The Brantry Boy."

"PULSE" is a special book, written with Damian Harvey, and it tells Mickey’s story. It's a story of his family in Ardboe, a wee village in a beautiful part of rural Ireland beside Lough Neagh. It’s the story of an Irish family of eight children, nurtured by Teresa and her husband Sean. It is a story of Mickey kicking ball on the Green with his brothers and childhood mates and then with the local Gaelic Athletic Club, O Donavon Rossa. The heart of Ardboe.

It’s about schooldays, meeting Peter Canavan when he came to teach in Holy Trinity College in Cookstown. It’s about fishing on Lough Neagh with his father. About British troops. Visits to his father in Belfast Prison. It’s a book about music, song writing, guitar picking. Doing local gigs. Visiting the USA. Getting on to the county football panel. It’s about that brilliant first Tyrone team to win the Sam Maguire Cup. It’s about Mickey Harte, legendary manager. It’s about Cormac Mac Anallen, one of Tyrone’s finest, who died suddenly, aged just twenty four. "The Brantry Boy."

It’s about New York. About Mickey knuckling down and working hard supported by others including Fay Devlin. About meeting Erin Loughran as she played the fiddle at a session. About Erin and Mickey making music together. Then making babies.

Mickey’s business was going well. He was blessed with a great family and friends. Immersed in the Gaeldom of New York.

Then, on 29 March 2021, aged forty one, Mickey had a massive heart attack. That’s when his life ended. Thanks to Erin, his own resilience and self-awareness as he confronted his "widow maker" and Orangetown police and other emergency workers. He survived. Montefiore Nyack Hospital did the rest and kept him alive.

And then it was a long hard struggle for Mickey to get back to himself again. This book tells all this and much more. It is especially poignant as Mickey recounts how he relearned what is important in life. It’s all here with wonderful clear and hopeful faith in love, family, friendship, community, Ireland and humanity.

Mickey’s appeal to the reader is for us all to play our own music in appreciation of what we have - not just materially, but more importantly, in our values. Because without those we have nothing. That is the essence of "PULSE." Read it for yourself. I’m honored that Mickey invited me to help launch his story. Thank you.

"PULSE" lets us know that Mickey and Erin have never forgotten where they are from and who they are. I wish them both, and their family, the very best of good luck for the future.