With the kind permission of the author, the Irish Echo presents this exclusive excerpt from 'Monaghan', the forthcoming novel from Irish American writer Timothy O'Grady. Readers can pre-order 'Monaghan' on publishing crowdfunding site Unbound. Timothy O'Grady will take part in an event at the James Connolly Centre, Belfast, this coming Wednesday (October 25) to raise funds for the publication of 'Monaghan', which is inspired, in part, by the story of Frank 'Lucas' Quigley, a legendary republican activist and artist from Ballymurphy, West Belfast.

The boy heard a melody in the night. He was sitting in the window of his room after midnight watching snow fall. The melody was slow, the playing soft, the sound like nothing he’d heard before, long, long notes like those made by a singer, some cries, some whispers. But the sound was not made by a singer.

The boy opened the window and felt the cold air move over him and into the room. The snow fell as feathers do on this night without wind, then sparkled in the spheres of light made by the streetlamps. The colours of the city – beige, slate, rust – and the lines which separated things were vanquished by the snow. Everything now was white, indefinite. It was as if clouds had come down and lay on the city. There was no sound but the melody. It seemed to slip through the falling snow. It was more like speech than music.

The boy closed the window and put his clothes on over his pyjamas. He took his coat from a peg downstairs and went out the back door into the yard. Everyone in the house, it seemed, was asleep. He stood still in the yard and let the snow fall over him. He realized that he’d never before been out so late at night. It was as if midnight were a frontier he had crossed for the first time. The music which he had heard faintly from his room now filled all the space he could sense around him. There was nothing else there, just darkness, silence. It was as if the people were not asleep, but rather absent. There was only him and the music and the falling snow in this place that was no longer Ballymurphy, or Ireland, or anywhere else known to him.

He went over walls, hedges, sheds and along alleyways, the snow falling down under his collar. Years later he would do this again, blood dropping onto the snow from a wound in his leg. When he did he would remember this night when he went looking for the music.

He climbed over the wall into the McGuigans’ yard and then over fences and around hedges, moving towards the music. As he grew nearer to it he could hear that in it there were two sounds, one like a long, groaning breath or rolling thunder, dying away and then finding life again, the other made of notes that dived and slithered and flew over the first sound. Sometimes the notes trembled before they faded. The night was cold and fresh and alive, the snow soft and light, the sky dark and vast. He felt he could go anywhere he wanted, out beyond the limits of the city to places unknown to him. He felt also the strangeness and the freedom of this. All this, he found, was in the music. It was as if the music described this rare night and him moving through it.

He went over walls, hedges, sheds and along alleyways, the snow falling down under his collar. Years later he would do this again, blood dropping onto the snow from a wound in his leg. When he did he would remember this night when he went looking for the music. He came finally to the last wall. On the other side was the sound he had been following. It was tremendous now, like an organ in a church. He felt it moving through the ground. He put his foot on a bucket and lifted himself up onto the wall.

He seemed to be looking then into an abandoned place, missing panes in the windows of the dark house patched with cardboard, in the yard the shapes of tyres, washing machines, engines, lengths of wood under the snow. An old man in an overcoat sat on a stool, playing the uilleann pipes. The boy watched his long fingers slide over the chanter. The man’s feet were covered with snow, his body rocked back and forth and his head dived like a swooping bird as he brought out the notes of his music. No one but the boy was there to hear him. Sometimes the man made a sound as if he were trying to lift a weight. The music rumbled in the ground, pierced and shook in the air. To the boy, it seemed that it was made inside the man, passed out through his hands and then moved towards and around him. It seemed to be explaining something to him.

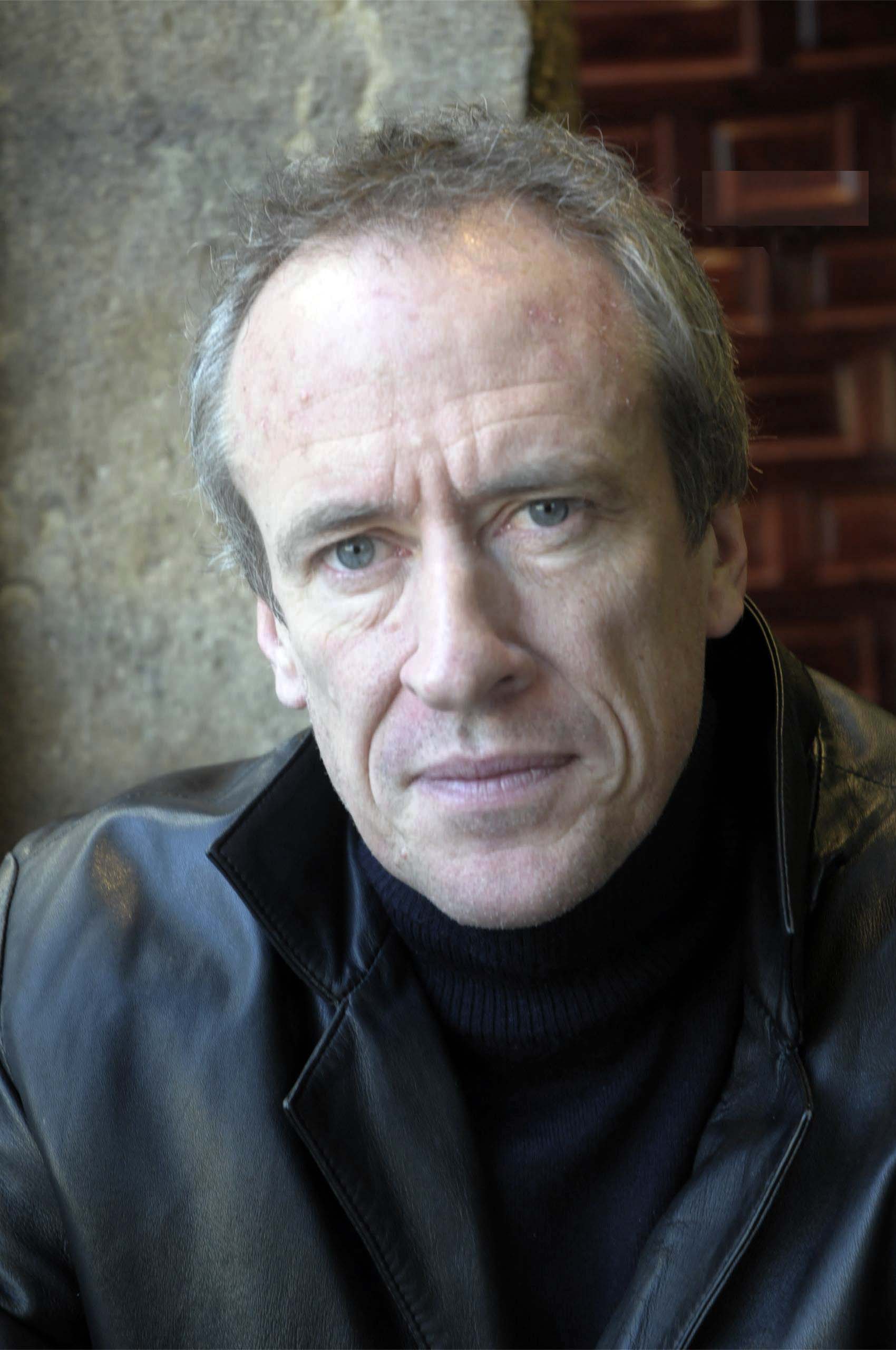

STORYTELLER: Timothy O'Grady

Finally the man ended the tune with a bow of his head and leaned back and lit a cigarette. He saw the boy leaning on the wall and looking at him.

Hello, lad, he said.

Hello, said the boy.

Do you like music?

The boy thought, then said, I don’t know.

Do you like my music?

The boy thought some more, then smiled.

Yeah.

Well, good. I’m glad. What do you like about it?

It’s like this night, said the boy.

He surprised himself when he said this.

That’s it! said the man. That’s it!

He got up from his stool and ran over to the wall where the boy was. The boy could see his face now, his uncombed hair, his liver spots, the patches of white bristle where his razor had missed. His skin sagged and it looked like no one cared for him, but his blue eyes were bright and young. He put his hands on the wall and looked up at the boy.

What about this night, lad? he said softly.

The boy wanted to tell him for he could see that the man needed something from him, but he didn’t know how to explain it.

I don’t know, he said.

The man laughed and went back through the snow and the objects of the yard to the stool where he had been sitting.

Don’t worry about it, lad, he said. It’s all right. I get you. I caught that tune out there in the night air and brought it here into the yard and played it. Just like that. You came to listen. So now you’ll want to be going home for you’d be tired, and I’ll stay here and play you something for company on the road.

The man put the pipes around him and began again to play. This was a different kind of tune, as light and easy as birdsong. The man’s cigarette was burning in the corner of his mouth and he had to tilt his head to keep the smoke from going up into his eye. Sometimes he laughed, as though he was finding jokes as he played the notes.

The boy got down off the wall and began to walk towards home. He listened to the tune as he made his way back over the walls, the notes seeming to sparkle and float like bubbles rising through water. He laughed sometimes too, but it was about the man he met rather than his music. Maybe not even the man, but the idea of the man, the way he’d picked that music out of the air and brought it out of himself as he moved his fingers over the instrument. The boy felt light and clear and alive and as though he were moving towards some new place where he wanted to be, this place where such things could happen. What he might do if ever he got there, though, he could not say.