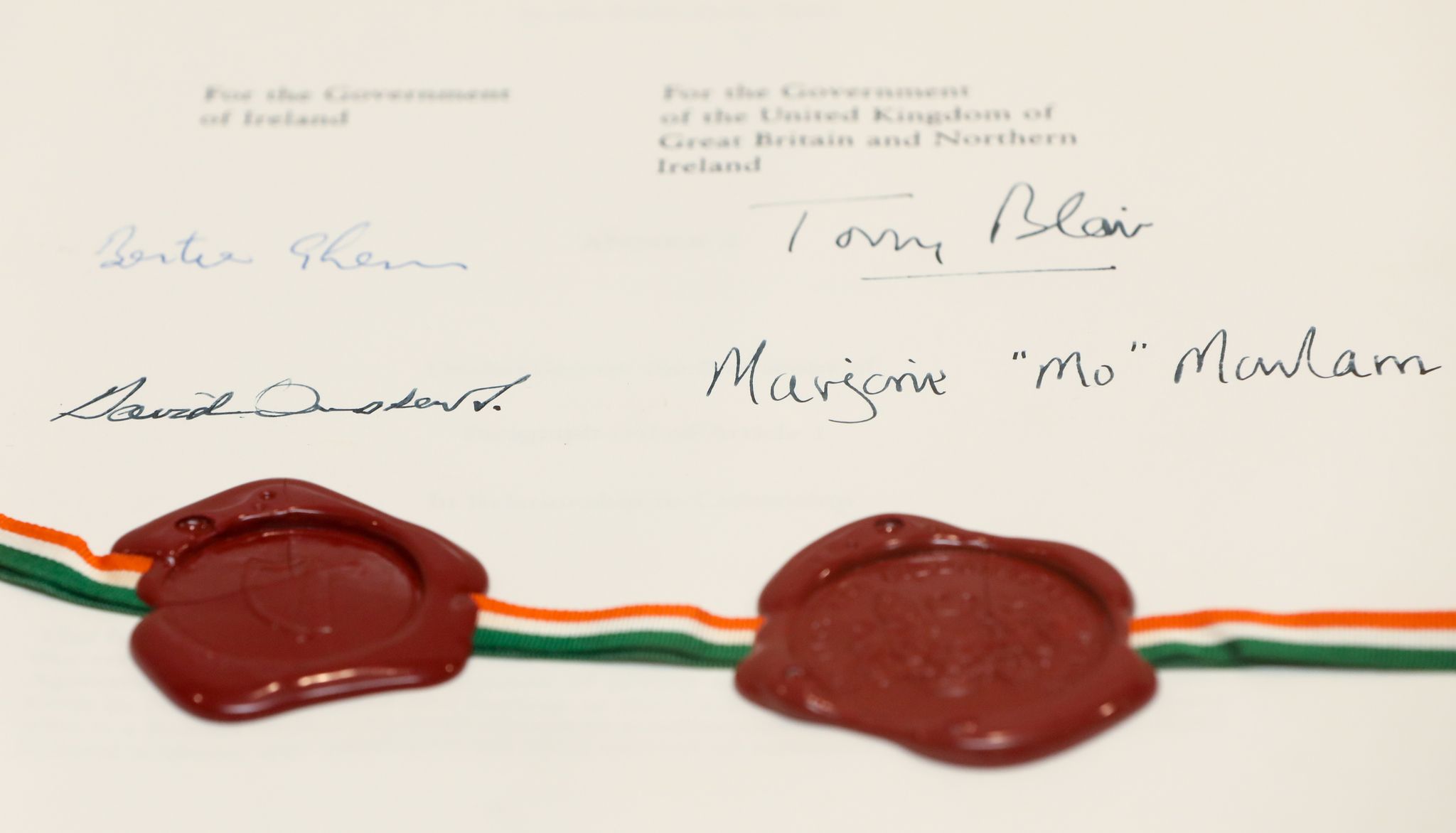

Sunday, May 22, marked 24 years from the historic referendum in May 1998 that saw almost three quarters of people in the North vote in support of the Good Friday Agreement.

Despite the twists and turns in the years since then the Agreement has proved resilient in maintaining peace and in plotting a course for constitutional, political and economic change in the North and across these islands.

Now the Good Friday Agreement is under threat. Arguably that has always been the case as far as elements of unionism are concerned. But for their part successive British governments have refused to implement parts of the Agreement. The Tories in particular have been guilty of this. Especially the current crowd.

The Agreement was a defining moment in our recent history. It underpinned the peace process. However the Good Friday Agreement was not a settlement. It provided the space in which our different political and constitutional perspectives, that are part of our shared colonial experience, can be debated and discussed and out of which a new future can be agreed.

For those of us who want it the Agreement provides a mechanism to achieve self determination and an opportunity to undo the disaster of partition and achieve a united Ireland democratically.

This essential part of the Agreement is now being targeted. The Agreement is clear. A majority is needed for constitutional change. However, there is currently a sinister effort underway by some to attack this core principle of the Agreement. There is a suggestion being made that it might be time for the provisions of the Good Friday Agreement to be rewritten. The Tánaiste Leo Varadkar went so far as to propose that any decision on a unity referendum should have a role for The Assembly.

The real politick is that any decision on a referendum will be taken by the two governments – not by a British Secretary of State. It is above his/her pay grade. Clarification on the criteria for this may be useful, but any suggestion that the Good Friday Agreement should be rewritten and this crucial aspect of it be amended, must be resisted.

The Good Friday Agreement has stood the test of time. Its flaws rest primarily with the failures of the two governments to fulfill commitments made. The British government is not to be trusted with our future. That is for the people of this island to decide.

The Agreement and the people of the North have not been well served so far by the current Irish government. An Taoiseach Micheál Martin has allowed relationships with the British government to almost disappear. Arguably, this is the British government's fault. I accept that.

But An Taoiseach has done little to counter this. He rarely mentions the North unless it is to attack Sinn Féin. His instinct on the issue is not good. For months there was no worthwhile contact between the two governments. That surely is An Taoiseach’s responsibility.

His government has refused to challenge the British government in a strategic and consistent way. When moved, by dint of public pressure, for example on London’s Amnesty for its forces or their allies, its attitude has usually been rhetorical and without real substance.

So the Irish government has a lot to do. It should be planning for the future in an inclusive, transparent democratic way. And it should be defending and implementing the Good Friday Agreement.

ACHT NA GAEILGE ANOIS

The echo of thousands of cheerful, excited voices raised in defiance reverberated off the buildings along Royal Avenue and into Donegall Place to the front of Belfast City Hall. The raised voices called for Irish language rights – for equality and respect. The slogans demanded:

Acht na Gaeilge – Anois (Irish Language Act – Now!!).

Tír gan teanga, tir gan anam (A country without a language is a country without a soul.

Saturday’s Lá Mor Dearg march, organised by An Dream Dearg, was undoubtedly one of the most colourful, exuberant, and spectacular protest marches that Belfast has witnessed in many years. From just before noon they began to arrive in their hundreds at An Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich on the Falls Road. Most were wearing the familiar red tee shirt with the white circle that is the symbol of Lá Dearg - the campaign for Irish language rights.

By 1 p.m. the hundreds had become thousands. A sea of red stretching across the Falls Road and packed into the small streets around it. Families pushing prams, parents carrying small children on shoulders, other children carrying their home made little posters -‘Acht Anois’; young people in their thousands. Laughing. Enthusiastic. Eager. Animated. Determined.

Banners from solidarity groups, trade unions, political parties. Colourful ethnic groups singing and dancing.

Unsurprisingly, the march was late starting but as it slowly made its way down the Falls Road in bright sunshine the extent of the huge number of people participating quickly became apparent. One enterprising activist put up a drone. The video footage is startling. The Falls Road and Belfast City Centre are filled by a long river of red shirts. The chants of the marchers can be heard plainly.

Cearta Anois, Acht anois (Rights Now, Act Now).

Támid dearg: Dearg le fearg (We are red, Red with anger).

Saturday’s march and the growth in Irish medium education is an example of what can be achieved even when British governments and unionist political leaders refuse to honour commitments and legislate for rights. The Good Friday Agreement in 1998 said that; “All participants recognise the importance of respect, understanding and tolerance in relation to linguistic diversity” in respect of the “Irish language, Ulster-Scots and the languages of the various ethnic communities, all of which are part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland.”

Specifically, and in relation to the Irish language, the British government committed to take “resolute action to promote the language” and to “facilitate and encourage the use of the language in speech and writing in public and private life where there is appropriate demand” and to “seek to remove, where possible, restrictions which would discourage or work against the maintenance or development of the language."

These commitments were not honoured. Eight years later at the St. Andrew’s negotiations the British government committed to the introduction of Acht nba Gaeilge. In the 16 years since then one promise has followed on from another and all have fallen as one deadline for Acht na Gaeilge has passed without the legislation being introduced.

Despite the prevarication, the stalling, the discrimination and antipathy toward the Irish language and Gaelgeoirí the resilience and resolve of Irish language activists and those citizens who support language rights has frustrated the naysayers and begrudgers. The use of the Irish language and the numbers of young people attending Irish medium education has grown year on year.

If you were not able to get along to Saturday’s Lá Mor Dearg then click onto the link and watch six minutes of video that will do your heart good. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oAhzTS-avtc

DEFENDING JOURNALISTS

The shameful decision by Israel to cover-up the murder of Palestinian/American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh by refusing to hold a criminal investigation into her killing will have come as no surprise to most people. In our own situation there are victims groups, representing hundreds of families, struggling for truth decades after their loved ones were killed by British state forces. Last week, the London government introduced its so-called ‘Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill’ which makes future efforts at truth almost impossible for victims.

Its real objective is set out in the second paragraph of the Bill which states: “For too long, veterans and former service personnel have lived in fear of prosecution for actions taken whilst serving their country in order to uphold the rule of law."

This is what rogue states do. They cover-up and protect the criminal actions of those charged with defending the policies, strategies and self-interests of governments involved in conflict. The apartheid Israeli regime has a long track record of this. So too have the British.

The families and victims are in the front line of challenging these decisions. So too are journalists many of whom are the target of vilification, censorship, threats and increasingly death.

According to Reporters without Borders, Shireen Abu Akleh is one of 35 journalists to have been killed and 144 to have been wounded by the apartheid Israeli regime since 2000.

Israel isn’t the only dangerous place for journalists. In the North, Martin O’Hagan and Lyra McKee were both killed as they carried out their work as journalists. Since the invasion of Ukraine media reports have put the number of journalists killed at around 20. Last year, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisaiton (UNESCO) reported that 55 journalists were killed worldwide.

There is an imperative on governments and the international community to defend a free press and to protect journalists.