Mam performed her usual magic over the open fire that Christmas Day in 1951 when I was 11. At dinnertime the glazed turkey, drumsticks in the air, lay on the blue Willow Pattern platter. The potatoes, cooked in the bird’s sizzling juices, were wearing new brown skins. The spout of the milk jug dripped dark brown gravy, marrowfat peas were piled in a Willow bowl, and the aroma of the stuffing was as enticing as the smell escaping from a baker’s kitchen.

When all the dinner plates had been finger-cleaned of the last traces of gravy and cleared away, Mam placed the steaming Christmas pudding in front of Dad. She had made it several months earlier, and it had aged in a gauze pouch hanging from a nail in the Dairy. Dad doled out the pudding and Mam poured the Bird’s Custard.

This Christmas season was different from those that had gone before; we had a radio. Powered by dry and wet batteries, it was ensconced in a recess in the thick kitchen wall. The radio’s aerial came through a hole in the frame of the kitchen window. Outside, the wire went up the pebble-dashed wall, over the slated roof to the chimney and from there across the farmyard to the corner of the Loft.

That morning we had listened to the king’s Christmas message on the BBC. Except for Mam, who liked to read about the British royals, we didn’t care what the king had to say; we just wanted to hear a voice coming into our kitchen from all the way across the Irish Sea. George VI sounded so ill that Mam said, “That lad will be dead in a month.” She was right.

Having the radio on early in the day was an anomaly. To save the batteries, Dad had decreed that it was only to be turned on at one p.m. and six p.m. for the news, weather forecast, cattle market prices and GAA games. But Mam listened to “The Kennedys of Castleross,” sponsored by Gateaux Cakes, when Dad was out in the fields.

At the one o’clock broadcast on St. Stephen’s Day, the Radio Éireann newsreader reported that on Christmas night a ship in the Atlantic, “Flying Enterprise,” had been thrown around so violently in a storm that its cargo had broken free and slithered over to one side. Now, 350 miles from Falmouth, the ship was listing. On board were 10 passengers and a crew of 48.

Out of my schoolbag I dug my tattered atlas. I found Falmouth in Cornwall on the south coast of England. With the point of a compass and the stub of a pencil in its leg, I measured off the spot where the ship was floundering in the Atlantic. Then I did some long division.

“If a ship can go 15 miles an hour,” I announced, “it would take nearly a day for it to get from Falmouth to ‘Flying Enterprise.’”

“A whole day!” Dad said. “That ship is finished.”

“Ah, Dad! Don’t say that. The sailors! They’ll all get drowned.” My lament changed our Christmas spirit into one of anxiety. For the remainder of the day we spoke quietly as if loud speech would add to the precariousness of “Flying Enterprise.”

At six o’clock we learned “Flying Enterprise” had been traveling to the United States. Under the captaincy of Henrik Kurt Carlsen, she had left Hamburg on Dec. 21 carrying, among other things, tons of coffee, tons of rags, some cars and many tons of pig iron. The storm was still raging and waves were 40 feet high. A spokesman for the shipping industry expressed fear that the Lutine bell in Lloyd’s of London would soon be rung once to announce the ship’s sinking.

In my bed under the blankets, the plight of “Flying Enterprise” continued to fill me with dread. I had just memorized John Masefield’s “Sea Fever” for school, and my otherwise landlubber imagination I saw the grey mist on the sea’s face, heard the wind's howl, and felt the great ship shaking; felt the wind, sharp as a whetted knife, flinging stinging spray and spume into my face. On the wallowing, wounded “Flying Enterprise” my stomach lurched like it did when we drove over Carn railway bridge in Joe Shortall’s crowded taxi on our yearly trip to Dublin. The remnants of all Christmas feelings were shivered away by the image of the huge vessel sinking beneath the waves into the cold and dark North Atlantic, the sailors all crying out for home.

Two days later Radio Éireann reported the ship was listing 45 degrees. Captain Carlsen had sent out an SOS. With his hands, Dad showed us what 45 degrees looked like.

On Dec. 29, a British ship, M. V. “Sherborne” came in sight of “Flying Enterprise” early in the morning. But for some reason beyond our understanding, Captain Carlsen did not want the British to rescue his passengers and crew. He knew an American ship was on its way, and he decided to delay the rescue until it arrived. But he asked “Sherborne” to stay close by in case “Flying Enterprise” suddenly showed signs of sinking. On the concrete floor of our kitchen I danced nervously and shouted, “Your ship is sinking! Who cares who saves them?”

The waves were so high that “Sherborne” and “Flying Enterprise” often disappeared from each other’s view. And conditions were getting worse just as the USS “General A. W. Greely” came into view at 12 o’clock. “Flying Enterprise” was lying on its side at such an angle that it was impossible to lower her lifeboats. So “Sherborne” and “Greely” sent out theirs. Wearing life vests, passengers and crew had to jump from the “Flying Enterprise” into the fearsome and cold water and paddle to the lifeboats. An elderly man drowned, but everyone else was saved.

Yet Captain Carlsen stayed on board.

“What’s wrong with him? Get off the ship! Get off!” I cried.

We didn’t know that when a ship is abandoned, it can be claimed, along with its cargo, by anyone with the wherewithal to take possession. Captain Carlsen hoped “Flying Enterprise” would be towed safely back to Falmouth, and that the ship and the cargo entrusted to him would not end up a total loss for the owners. While he waited for the tugboat Turmoil, which had set out from Falmouth to tow him back to England, Captain Carlsen managed to get some rest for four days and nights, sleeping in an area from which he could jump off if the ship began to sink.

On Jan. 2, 1952, the day we returned to school after the Christmas holidays, another ship, USS “John W. Weeks” arrived, and the two merchant ships, “Greely” and “Sherborne,” departed.

The next evening at 6 we heard that the tug “Turmoil” was closing in on the floundering ship. Mam and Dad let us stay up for the 10 o’clock news, and when it was announced that “Turmoil” had arrived late in the day, we cheered, “He’s safe! He’s safe!” In the dark, the “John W. Weeks” used her searchlights to guide the tugboat up close to “Flying Enterprise.” But the heaving water made it impossible to get a towline across.

On Jan. 4 the crew of “Turmoil” managed, after many efforts, to throw the towline onto “Flying Enterprise.” But because of the deck’s angle, Captain Carlsen was unable to secure it by himself. When “Turmoil” brushed up against the listing ship, the tug's mate, 27-year-old Kenneth Dancy, leaped toward “Flying Enterprise” and grabbed the deck railing, which was only a few feet above the water.

“He jumped onto a sinking ship!” Dad said. “He’s mad!”

“He’s brave,” my oldest sister said.

With Dancy’s help, Captain Carlsen secured the towline. And finally, listing at 60 degrees, and over 300 miles from Falmouth, “Flying Enterprise” began the long journey to safety behind “Turmoil.”

Our family, far from the sea, far from Falmouth and knowing nothing about ships and the men who go down to the sea to sail them, waited anxiously. Into our prayers we slipped pleas for the safe return of “Flying Enterprise,” Captain Carlsen and Kenneth Dancy. Each evening, our kitchen fell silent when the radio announcer said, “Here is the news,” and told us how many miles the wounded vessel was from Falmouth harbor.

“Look at the map. Why don’t they go to Cork?” Dad asked.

On Jan. 10, as I had been doing since my return to school, I ran home to get the latest news. When I reached the top of the Furry Hill, I saw Dad out in the field behind Missus Fitz’s house. He was breasting the far hedge with a billhook.

“Dad!” I shouted. “Did they get to Falmouth?”

“Not yet!” he shouted back. “The towline broke.”

“How many more miles?”

“46.”

When the 6 o’clock news came on, Dad was out milking the cows and Mam was frying eggs and potatoes for supper.

The radio announcer spoke soberly.

“Here is the news…Today, Captain Carlsen and Kenneth Dancy abandoned ‘Flying Enterprise’ at 20 minutes after 3. At 10 minutes after 4, the ship sank.”

My siblings, Mam and I erupted in tears and loud laments. Dad appeared in the kitchen doorway, stood for a moment, then wiped his nose on his sleeve. He turned back into the farmyard.

Later that night Radio Éireann presented a program about the last hours of ‘Flying Enterprise.’ Rather than dwell on its sinking, the reporters spoke of the devotion to duty shown by Captain Carlsen and Kenneth Dancy. They told of how, when the towline broke, the lighthouse maintenance ship ‘Satellite’ and the tugs “Dexterous” and “Englishman” had gone to “Flying Enterprise” as if they were family members on their way to comfort a dying relative. And when ‘Flying Enterprise’ finally went down, those ships blew their whistles and sirens and foghorns in a mournful farewell.

I hadn’t felt so sad since my Granny died when I was 5.

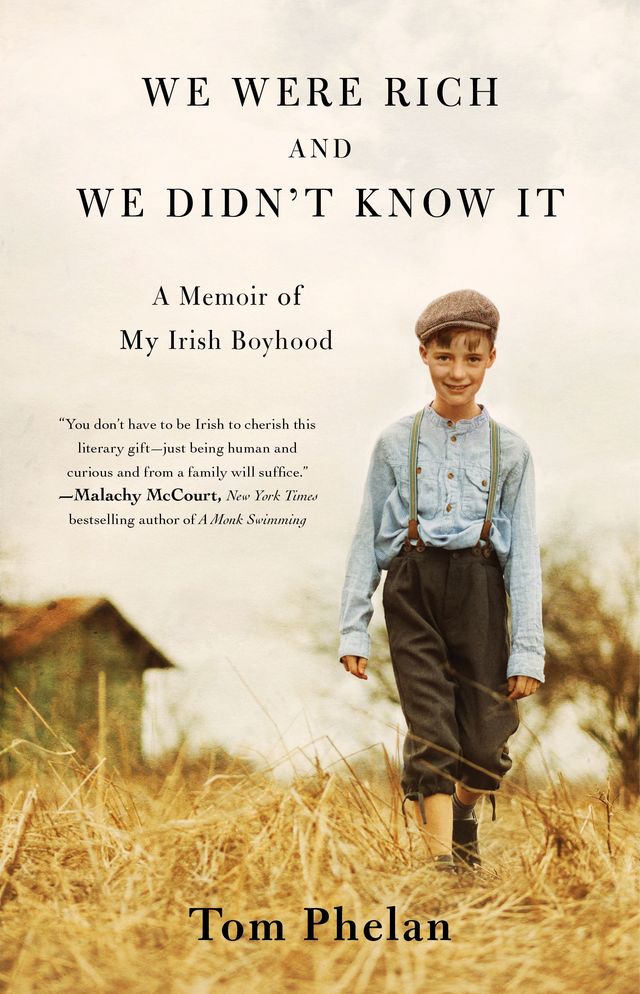

© 2021 by Glanvil Enterprises, Ltd. A native of Mountmellick, Co. Laois, Tom Phelan is the author most recently of “We Were Rich and We Didn’t Know It: A Memoir of My Irish Boyhood.” For more about that and other books, visit his www.tomphelan.net.

BOOK COVER-3.jpg