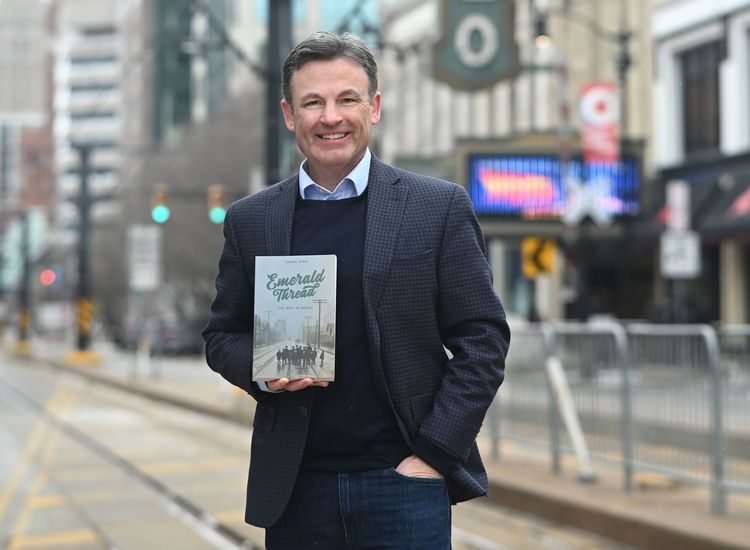

Richard Flanagan’s seventh novel, “First Person,” was published recently in the United States. His sixth, “The Narrow Road to the Deep North,” won the 2014 Man Booker Prize. PHOTO: JOEL SAGET

Page Turner / Edited by Peter McDermott

One of the many admiring U.S. reviewers of Richard Flanagan’s “First Person” said the narrator struck a “Faustian bargain,” which would suggest that for Kif Kehlmann there’s some sort of upside involved. However, there may not even be that.

Kif is a struggling novelist with one pair of shoes to his name, Adidas Vienna runners, and the leather is tearing away from the right sole. That might be okay if he didn’t have a family – a wife pregnant with twins and a 3-year-old – to support. So, he accepts the offer to write the memoirs of Siegfried Heigl, who is about to go to trial in Melbourne for defrauding the banks of $700 million. It’s a $10,000 paycheck for just six weeks’ work. He accepts, figuring he has a jump on the project as Heigl has himself written a 12,000-word manuscript. But that proves to be of little use and in person the subject is a very difficult interviewee: “At best, Heidl answered in irritating riddles and, at worst, was distracted or, worse still, entirely uninterested.”

Meantime, just as the young writer feels he’s being increasingly corrupted by Heigl’s mind, his bestseller-obsessed publisher is piling on the pressure to see some chapters.

Flanagan, who lives in his native Tasmania with his wife and family, won the 2014 Man Booker Prize for his sixth novel, “The Narrow Road to the Deep North,” which was set during World War II. It was inspired in part by his father’s time in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. “First Person” – Flanagan’s own experience with Australian conman John Friedrich is the spark in this case – has a more contemporary focus. The Washington Post said, “At a time when our truth is daily contorted, debauched or ignored, we require Flanagan’s artful reminder of the wreckage caused by our unwillingness to say what happened.”

More generally, the New Yorker commented, “The novel, with its switchbacking recollections and cyclical dialogue, its penetrating scenes of birth and, eventually, death, is enigmatic and mesmerizing.”

In the opinion of the Seattle Times’ reviewer, “Flanagan places you vividly in Kif’s mind," while the New York Times’ said, “Heidl as a character is deeply compelling.”

What is your latest book about?

A ghost writer writing the memoir of a con man. Any resonance for an American audience is an accident of history.

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

Sitting upright helps.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Write.

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

“Anna Karenina,” “Anna Karenina,” “Anna Karenina.”

What book are you currently reading?

J M Coetzee’s “Life and Times of Michael K.” Ali Smith’s “Winter.”

Is there a book you wish you had written?

The one I am trying to write.

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

“When I sing I feel I am touched by God” (Elvis). We have their books. To want more is to misunderstand what is divine in every work of art and what is human in each of us. So: none.

What book changed your life?

Life changes life.

You're Irish if…

you’re from Ireland. I am not. I was born in 1961, in the small village of Longford, Tasmania, where my great-great-grandfather, Thomas Flanagan, had been sent to work as a convict-slave for a sheep farmer in 1851. He had been a leader of local opposition to the English in Roscommon over the inadequate famine relief, and a few months later was sentenced to transportation to Van Diemen’s Land for stealing seven pounds of cornmeal. We were by that time 110 years out of Ireland and I was descended from Irish convicts on all sides, almost all sent out to Van Diemen’s Land during the Famine, most for stealing food, some, such as my mother’s great-grandfather, for political crimes, he being a member of a revolutionary Gaelic-speaking secret society, the Whiteboys.

On their release, the convicts were not allowed home. Generation after generation, they intermarried and made up a strange mad peasantry, the bottom of the working class. We believed we were still Irish, and it was only on visiting Ireland as a young man that I discovered this for the sorry illusion it was. Yet nor had we become fully Tasmanian or Australian, but were rather lost in some strange other world. We were this other thing, part snap-frozen pre-Famine Irish, and part of the other island with all its mad wounds, its endless stories and its staggering beauty.