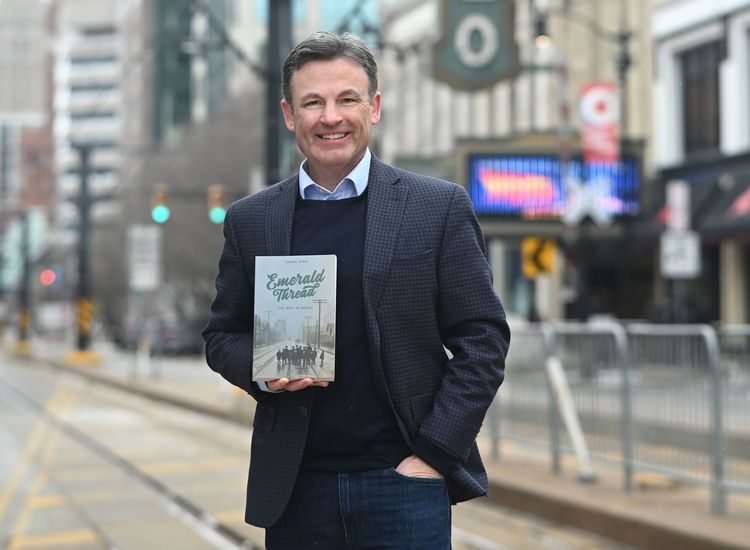

Brian Flynn, outside a center named for his great-uncle Michael J. Quill, has proposed a Marshall Plan for the American Worker.

By Peter McDermott

Brian Flynn believes fighting the good fight should be enjoyable.

He has, in that regard, a powerful role model from his own family, a famous labor leader he never met

“There are audios of Mike Quill,” he said of the County Kerry-born Transit Workers Union of America leader who died in 1966, “waiting for the police to come arrest him and he’s having so much fun.”

It’s an attitude that helps Flynn, the presumed frontrunner in the crowded Democratic primary in New York’s 19th district, project a calm demeanor in the face of persistent, often anonymous negativity and a process corrupted by money. And indeed it is fun mostly, even though, he allowed, that there are times when those other factors can make it “tough on the soul.”

Flynn has faced a lot worse in his life. On Dec. 21, 1988, his older brother John Patrick, known to everyone as J.P., was killed on Pam Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie in Scotland. The 21-year-old was on a study abroad program with Syracuse University.

“I was a 19-year-old college kid,” Brian Flynn said. “That’s when life changed forever.”

He became an activist, and has remained one.

“My brother was the boy next door,” he said of J.P. Flynn. “He was a kind soul.”

Flynn’s natural instinct was to fight for justice on his dead brother’s behalf. As for his mother Kathleen, who was Quill’s niece and goddaughter, he said, “She quickly moved through shock and sadness, and found her comfort zone, which was anger.”

Within days of the tragedy, both were down at the White House protesting “to hold our own government accountable, to hold the corporations accountable,” recalled Flynn, who has two younger twin sisters.

“We proved willful misconduct and gross negligence,” he said, “which is a very high bar to prove in a court of law and we changed airline regulations to prevent that type of bombing ever happening again.”

Those early adult experiences – which included working with Robert Mueller, who had a leading role in the investigation – made the issue of national security a priority for him. He is also an entrepreneur and a long-time progressive, one who is policy-literate across a whole range of issues.

Flynn and his wife, the novelist Amy Scheibe, went to a political meeting near their home early last year and heard a key local activist describe as the perfect candidate someone with more or less the above type of profile. His wife elbowed him, encouraging him to introduce himself to her. He did and the woman at first approached the idea of his candidacy with an abundance of caution. “She didn’t make it easy,” he said, but added that she is now his political director.

He and Scheibe — a North Dakotan he met when she worked in publishing in New York City — settled down 15 years ago in Greene County. That made him the third-generation Flynn in the county — as his grandfather had been a bartender in Leeds and his father had grown up there — and the couple’s 14-year-old son and 12-year-old daughter the fourth generation.

Now he’s vying with five others for the chance to unseat the incumbent Congressman John Faso, who was Eliot Spitzer’s GOP opponent in the 2006 gubernatorial campaign. Flynn believes he can win the primary and then beat Faso in a district that voted for President Obama during his reelection bid in 2012. “He’s good and he’s tough. But he’s vulnerable,” Flynn said of the Republican.

The last time Flynn ran for election, he revealed, was in the 8th grade. He won. A rather more important moment in his life, though, was his unsuccessful candidature in his late 20s for a job in the company he worked for. The person who did get it told him that while he was regarded as a valuable member of any team he was on, was admired for his persistence and had several other fine qualities, he would never make into the “inner sanctum” of corporate America. Why? He was too much of a rebel, she said.

“She’s a supporter of mine today,” he said.

Factory-floor insight

Flynn had always seen himself in any case as a natural entrepreneur and so he broke out on his own. He formed a software company and then a media company, before setting up a consultancy with Ed Schlossberg called Schlossberg: Flynn. They’d collaborated before, and Scheibe had worked with both Schlossberg and his wife Caroline Kennedy on book projects.

“Ed helped me tremendously in my career and my life,” he said.

Their consultancy, according to its website, finds “companies with great potential” and helps them grow “through business development, strategic marketing, and financing. Our industry expertise is concentrated in the technology, financial services, media, health/wellness and manufacturing.”

Through that work, Flynn became directly involved with a company that makes medical devices.

“It was on the edge of bankruptcy and the banks and the owners said ‘See what you can do to fix it.’ A group of us went in there and turned the company around,” he recalled. “We stabilized it and it was a great experience. We’ve grown that company from $20 million to over $100 million today and 400 jobs here in America.

“We raised our average worker’s pay by 40 percent,” he said. “We did that by investing in training and in up-skilling the employees.”

Flynn’s experience close to the factory floor, he believes, gives him some insight into the problems faced by workers today.

“Automation and artificial intelligence are eviscerating the working class,” he said.

“Infrastructure, though, can’t be done by robots. We just gave away $1.4 trillion of taxpayer money that we borrowed to major corporations and rich people. We could have invested $300 million of that money in a program that would really energize the infrastructure,” he said.

The nation’s education priorities don’t help much. Flynn said that “80 percent of Americans think they should go to a four-year college because we’ve told them that.”

Of those who do go, “half don’t finish, but they go into a debt, a lot of debt.”

The Germans have the right idea: 60 percent of young people go to trade school or an apprenticeship. “We have to have an honest conversation with our kids, ‘Listen, maybe a four-year academic career is not what you’re looking for. Maybe you would have a more fun and interesting life if you went and got a technical degree.’”

He believes that the Democratic Party is no longer seen as the party of the American worker. Partly it’s a question of messaging. He points to the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare, which was a huge step in a progressive direction and a major job creator. But it’s telling for him that people rallied to it only when its benefits were jeopardized.

A bigger issue for the Democrats, however, in Flynn’s view, has been the overall lack of policy substance.

“What can we do that as a country, not just as Democrats, to create an America that works for everybody, not just for the few?” Flynn asked.

To that end, he has proposed what he calls a “Marshall Plan for the American Worker.”

Flynn, who would like to see a woman emerge as the Democratic candidate for president in 2020, said there is no American politician he can think of who is championing the interests of the worker.

He himself has always had a trade-union awareness because of his famous uncle. “He wasn’t tilting at windmills. He got the work done,” he said of Quill who was an early white Northern supporter of the civil rights agenda of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Flynn joined the National Allied Workers Union more than a decade ago, and continues to pay his dues and receive his health insurance in that way. And recently it was reported that his campaign staff was unionized with his support.

When experiencing rough periods, as entrepreneurs inevitably do, he said he always prioritized meeting workers’ pay, taxes and benefits, ahead of his own, even if that meant delving into his own personal savings account. That’s something, he feels, some younger people don’t fully understand.

They might not fully get, either, the closeness of immigrant families with uncles and aunts and cousins in mid-20th century America. Mike Quill and the former Molly O’Neill didn’t have their only child until some years into their marriage and so Molly’s brother’s children — Kathleen and her siblings — became their stand-in family.

“When you’re growing up in New York City in the 1950s and ‘60s and your uncle is this hero of the working man, it’s part of who you are. She always talked about him,” Flynn said.

As a salesman and later a sales executive, his father wasn’t in a union, but his mother as a teacher was. “It’s part of who we are,” Flynn said.

“When she was working as a young woman as an intern at a radio station,” Flynn said of his mother who has been in poor health in recent times, “there’s this great picture we have of her with her Uncle Mike who came in for an interview during one of the strikes.”

Special interests

Kathleen Flynn would next be in the spotlight 22 years after Quill’s sudden death from a heart attack, and the union leader’s goddaughter turned out to be quite the “firebrand,” to use her son’s word.

The family had visited J.P. for Thanksgiving in November, which his surviving brother remembers as a “quick crazy trip” meeting up with cousins in Manchester and London. On their way to pick up J.P. at Kennedy Airport three weeks later, he and his mother stopped off at his grandmother’s home in the Bronx to help her prepare for a Christmas celebration with an expected 40 or so family members. Then the phone-call came from his father: he’d heard a news report about a plane coming down over Scotland.

The activism that began during those dark days was in time extended into support for public education and against conservative moves towards privatization and vouchers. He also taught English to undocumented workers and became passionate about their rights.

In the early years of the 21st century, believing his party to be too obsessed with merely being anti-George W. Bush, Flynn formed the Democratic Agenda, which promoted single-payer health care, aka Medicare For All.

“It’s logical and makes sense. You just have to take on the special interests,” he said, referring to the health-insurance and pharmaceutical lobbies. “The hospitals want it [single payer]; doctors want it.

“It’s just crazy in America that we have this unbelievably corrupt system,” he said.

The special interests’ money, courtesy of the Citizens United and McCutcheon decisions from the Supreme Court, has become even more important over the last decade.

“It’s worse than you think,” he said, meaning it’s worse than he thought and that was after 30 years’ involvement in politics. He saw it up close decades ago with the oil lobby’s reaction to the Lockerbie bombing, but his response and his credo, the family credo, has remained the same.

“You see something wrong, Flynn said, “You have to do something about it.”