After the madness of St. Patrick’s Day every year it is time for the other March madness, college basketball’s National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Men’s championship, which is one of the most watched sporting events of the year.

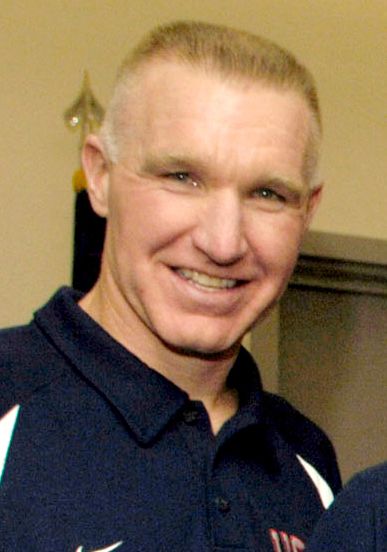

This year St John’s University, which earlier this month won the Big East Championship, is one of the tournament’s top contenders. Any Irish American of my age cannot think about St John’s basketball team without also thinking about perhaps its greatest player ever, Chris Mullin. Raised by a devout Irish American mother who instilled in him the values of hard work and discipline, Mullin went on to have an illustrious NBA career. Mullin combined a passionate love of the game with a legendary work ethic. Though never gifted with great speed or elite athletic gifts, he achieved what few in the sport ever have. He is a five-time NBA all-star and four time All NBA member. He is also two-time Olympic Gold medalist and a two-time Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductee (in 2010 as a member of the the gold medal winning 1992 USA Men’s Olympic Basketball—"The Dream Team"—and in 2011 for his individual career). Mullin was born on July, 30, 1963, into a tight-knit Irish American family. He shared a room with his three brothers, playing two-on-two basketball on a backyard court built by his father, Rod, who worked grueling 16-hour shifts as a customs inspector at JFK Airport to support his family. “They were bloodbaths,” Mullin’s younger brother Terence said. “Everybody loved to come to our yard and play. The games there were pretty much legendary for the neighborhood.”

Mullin came of age watching the great New York Knick teams of Clyde Frazier and Willis Reed, but his idol was the Boston Celtic player John Havlicek, whose number 17 Mullin wore in honor of his boyhood hero. A legendary gym rat, as a boy he got a key to the gym at nearby St. Thomas Aquinas, where he would work for hours honing every aspect of his ever-improving game.

When it came time to go to high school, Mullin initially chose to attend Power Memorial High School, a legendary basketball factory that produced Hall of Famer Kareem Abdul Jabbar and others. There he befriended future pro Mario Ellie who would bring Mullin to the city’s best pickup games, often in the roughest parts of town that saw very few Irish-American faces. Afraid to enter these dangerous areas alone, Mullin would meet Elie at the train station, and the future pros would walk to the court and back together.

Standing out as the lone white player in these overwhelmingly black and brown neighborhoods, Mullin’s game soon earned him the respect of the locals. “Chris loved to play anywhere, so I’d meet him, and we’d go to the hood,” Elie told the New York Post. “If you had a good game, you’d get a pass the next time you came to the wrong neighborhood. He got respect and a reputation and was always welcomed back. When he’d leave, they’d say, ‘Man, this guy could play.’”

Mullin gained much of his early confidence from those games set in hostile surroundings. “For me, going up to a neighborhood if I had a bad game, I might not be allowed to come back,” Mullin said, “That was real pressure.”

He transferred to Xaverian High School in Brooklyn in his junior year and experienced a six-inch growth spurt. Mullin defied critics who branded him as slow and un-athletic by leading his school to the New York State High School Catholic championship while being named “Mr. Basketball” “in his senior year.

“The way he saw the game, he had a mind that’s a gift that comes from somebody other than coaches,” said Jack Alesi, Mullin’s coach at Xaverian. “That comes from a higher being.” Though he was heavily recruited by bigger schools as a high school senior, he decided to stay in the city and attend St. John’s University. Mullin would star at Saint John’s for legendary coach Lou Carnesecca. He averaged 16.6 points per game in his freshman year while setting the school freshman record for points scored. In his next three years for the Redmen (now known as the Red Storm), he earned Big East Player of the Year honors three times, All-American honors three times and played for the gold medal-winning 1984 Olympic team. As a senior who averaged 19.8 points per game, Mullin led St. John's to the 1985 Final Four and its first #1 ranking since 1951.]

Mullin, who averaged 19.5 points per game, finished his career as the Redmen's all-time leading scorer with 2,440 career points. He also holds the honor of being one of only three players in history to win the Haggerty Award (given to the best college player in the New York City area) three times consecutively (1983–1985). Mullin was also named the Big East conference's player of the year, making him the only men's basketball player to receive this award three different seasons. He also won the 1985 Wooden Award and USWBA College Player of the Year Award.

Mullin was highly touted to have a brilliant career as a professional. He had hoped to be drafted by the New York Knicks but instead ended up being drafted by California’s Golden State Warriors, which meant living for the first time in his life away from his family and his New York support network. He achieved success on the court, but he was also lonely, and he racked up huge phone bills constantly calling home. Soon he found solace in alcohol, an addiction that plagued his father and uncle. By his third season he had developed such a serious drinking problem that his coach Don Nelson suspended him from the team.

At 24, Mullin entered a month-long rehab program, spending roughly six hours in meetings and therapy each day. One of the most difficult times in his life became the “best thing” that ever happened to him. “I needed to regain control of my life,” Mullin told the New York Times in 1989.

“I would never have taken the step and gone into rehabilitation, had Coach Nelson not pushed me toward it.” Mullin said. “When I got out of rehab, I knew in my mind what I wanted to accomplish. I didn’t know how it would work out. … Who knows what the future holds?”

Mullin overcame the addiction — like his father — and never took another drink, replacing alcohol with the relentless workouts that would become his trademark.

After beating the bottle, he put together five amazing consecutive seasons. Having moved to small forward, the 6-foot-6 Mullin made the All-Star Game each season, averaging more than 25 points a game and twice leading the league in minutes played, a feat that only the legendary Wilt Chamberlain accomplished. During that stretch, Mullin won glory as part of the greatest basketball team ever assembled, playing on the 1992 USA Olympic Dream Team with some of the legends of the game. The team’s Hall of Fame Center David Robinson learned that stories he had heard about Mullin’s legendary workout were not even half true.

“If there’s anybody that has a laser-focus mentality about basketball, it’s him,” Robinson said. “He was a maniac working out. I never saw anyone like that. When you talk about someone who just loves basketball and being around basketball, he’d be the guy you talk about.” His teammate Magic Johnson said, “When God made a basketball player, he just carved Chris Mullin out and said, “This is a player.”

Mullin eventually began to slow down and was traded from the Warriors to the Indiana Pacers where he played for another legend, Larry Bird, for three years before returning to Golden State for his final professional season.

He did basketball commentary after his retirement and worked as an NBA executive. On March 30, 2015, Mullin accepted the vacant head coaching position at his Alma Mater St. Johns. In the 2018–19 season, his team reached the NCAA tournament as they went 21-13 and reached the Final Four. The 21 wins matched Saint John’s highest victory total since 1999–2000.On April 9, 2019, Mullin resigned as head coach after compiling a 59–73 record in four seasons, including 20–52 in Big East play, citing a "personal loss" which was understood to be the loss of his brother.

Mullin is the father of four children and a devout Catholic who credits his faith as a guiding force in his life. Inducted into basketball’s Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame in 2011, Mullin asked his St John’s coach Lou Carnesecca to join him on stage for his speech — with family, friends, former teammates and nuns he knew growing up in the crowd. Before speaking, Mullin looked at his former coach, a boy from Brooklyn still amazed by what he had achieved. “Coach, it’s hard to believe we made it this far,” Mullin said.

Mullin is sure to be watching St John’s during the National Tournament and hoping that they can rekindle some of the magic he produced so long ago.