A central tenet of colonialism highlights the superiority of the ruling power in all facets of cultural expression.

So, in 19th-century Ireland, the British overlords stressed in their words and attitude that their system of government, their literature, their games, their religion, and, of course, their language, were far ahead of anything practiced locally.

The Gaelic Revival, which included the foundation of the Gaelic Athletic Association and the emergence of outstanding Anglo-Irish writers like William Butler Yeats and John Millington Synge, rejected these foreign suppositions of Irish inferiority.

The Gaelic League, founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde, son of a Protestant rector from county Roscommon as president, focused on promoting the study and use of the Irish language.

They got a positive reception in all parts of the island because the second half of the 19th century was a time of burgeoning nationalism where a country’s language was highly valued.

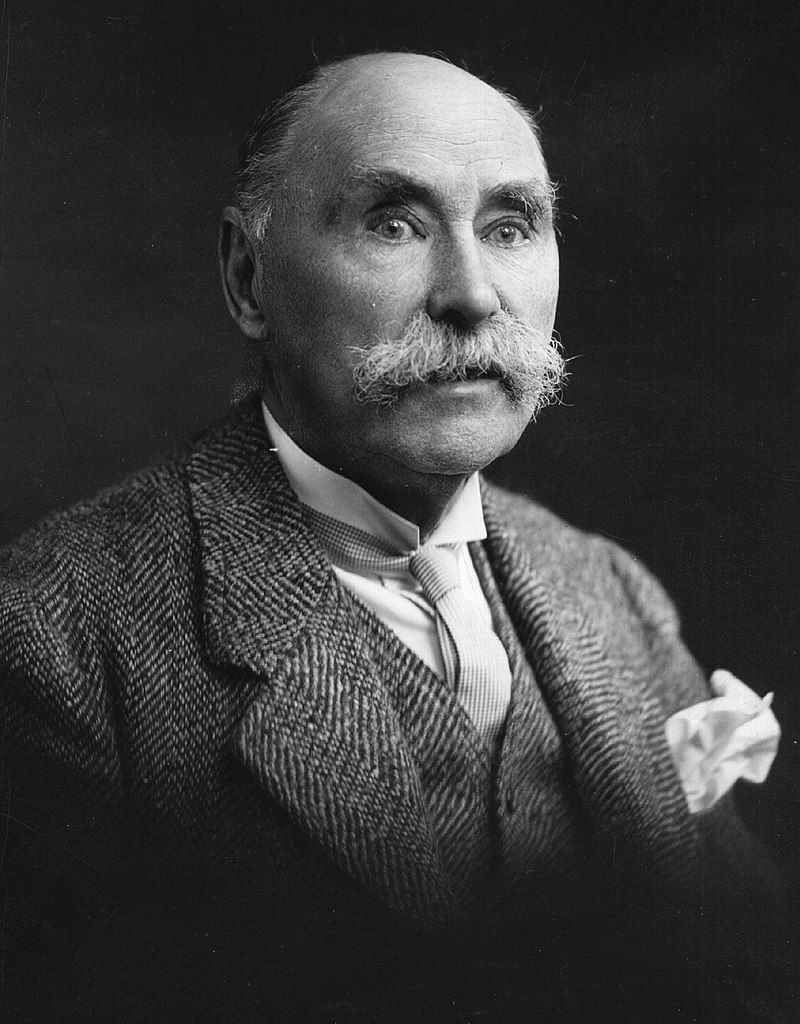

Douglas Hyde.

The League faced an uphill battle mainly because of negative economic forces in the country.

I am reminded of the words of Bertolt Brecht, the great German playwright from those years who advised activists: “Food first, then morality and culture.”

Analysis of the 1881 census reveals that about 45% of those born in Ireland in the early decades of the 19th century were brought up as Irish speakers.

Still, figures from the 1891 public records suggest that the Irish-speaking population had dropped to less than 4% - a major language transformation in less than a century. The history of my father’s strongly nationalist family growing up during the very early years of the 20th century in Lauragh, near Kenmare in County Kerry, illustrates this dramatic change.

My grandparents spoke Irish to each other at all times, but they insisted that their ten children communicate in English because they knew that, in their words, “they were for the boat.”

All but two immigrated to New York. Ireland was predominantly an agricultural country. The Irish-speaking Gaeltacht areas are mostly located in the poorest land along the west coast, from Glencolumbkille in the wilds of Donegal through the long coastal stretches around Connemara to the Dingle peninsula in Kerry.

At that time, the size of a farmer’s herd often determined his sense of self-worth and his standing in the community. The economic reality in the Gaeltacht areas certainly stymied the promotion of the language.

The two sides who fought in the savage Irish Civil War did not disagree about the pre-eminent place of the Irish language in the emerging country. Their leaders, all devout nationalists, pledged to promote policies that would bring about a revival of Gaelic as the principal mode of popular communication, marking the people apart from other countries, especially from England.

The first Irish government, led by William T. Cosgrave, believed that the schools had to produce natural and fluent Irish speakers, and they strongly encouraged teachers to focus on achieving that goal.

However, many teachers had little knowledge of the Irish language and resented that skills in other needed academic subjects were being diminished in pursuit of government language policy.

In 1932, Cosgrave was replaced as prime minister by his nemesis, Eamon de Valera, who was a fluent Irish speaker and displayed his undoubted scholarship at every opportunity.

However, Dev continued focusing on the schools to lead the chimeric revival but with no better success than his predecessor.

The policy was a disaster, as children all over the country rejected the idea that they had to pass Irish exams to achieve academic success.

Furthermore, to this day, many graduates from the school system cannot carry on a basic conversation in the language. I witnessed this during my first year teaching at the College of Commerce in Rathmines in Dublin.

At that time,1970 to be exact, it was common to have secretarial classes for girls focusing on developing office skills – mainly shorthand and typing – who also were required to meet the language and mathematics standards set by the state.

I was assigned to teach Irish to a class of these students, following the Department of Education curriculum leading to the Intermediate certificate examinations held each June. It was a painful experience because most of the fifteen and sixteen-year-olds I was paid to teach every day had no interest in the subject, and, worse still, they resented that they were forced to sit through the class.

The book assigned for reading for the Intermediate test was titled “Brian Og.” It dealt with a country boy who escaped Ireland during the Penal Times to study for the priesthood in Spain.

They did not relate well to this bucolic story, which heightened their sense of disaffection from the class and its teacher. I realized the kids weren’t to blame for this charade of a language program. They mostly sat with an air of silent endurance, waiting for the class to end so that they could get on with their real lives. Irish language proponents and cultural commentators report on important progress in a few areas, especially over the last quarter century.

More people speak Irish in Dublin today than at any time in the past one hundred years. Groups of mostly middle-aged and middle-class people gather to converse in Gaelic in various clubs and halls partly to improve their language skills, but also to enhance the social dimension of their lives.

This is a regular feature of nightlife activities in the capital. In Belfast, the musical and cultural group Kneecap is having a significant impact on the Irish entertainment scene. They are riotous, irreverent, strongly nationalist, and openly enjoy singing in their native tongue.

The highly-rated movie "Kneecap" is Ireland’s entry at the upcoming Oscars. Many commentators see the Kneecap rappers as transmitting a lasting love and respect for the Irish language.

Enthusiasts see this Belfast phenomenon as a clear harbinger of new attitudes to the language among young people, many of whom are convinced that the glory days are just beginning. Another positive development can be seen in the dramatic growth in the number of gaelscoils where all subjects are taught in Irish. Over 40,000 attend these primary schools, and around 12,000 go to all-Irish secondary schools.

All of this educational activity takes place outside of the Gaeltacht areas.

Some object that these schools encourage elitism among the attendees, but, beyond doubt, they are producing graduates who are well-versed in the language, and promising numbers of pupils attend similar schools in Northern Ireland.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com