I spoke this week to a friend in my hometown, Kenmare, in County Kerry, about a recently ordained priest assigned to the local parish. Today, this is news, but he recalled that when he was a young man you would meet a priest around every corner in the town. Then, there were three priests assigned to the parish and many more in ancillary churches nearby. Now, one priest has to take care of all the presbytery duties.

This major change in the role of the Catholic Church in Irish life highlights the wider cultural movements that have taken place throughout the island in the last half-century. The clergy statistics speak trenchantly to this revolution.

Fifty years ago, there were more than 14,000 women religious in Ireland. Today that number stands closer to 4,000, with an average age tipping 80. In 1960, the national seminary in Maynooth was populated by nearly 500 seminarians; this year, that figure dropped dramatically to around 20.

While 84% of the people self-identified as part of the Catholic church 15 years ago, that number has since dropped significantly to 69% - still more than two out of three people in Ireland. In addition, Sunday mass attendance remains one of the highest in Europe.

Ireland still has many churches but not so many church goers.

14% of respondents in this report ticked the “no religion” box, up by one-third from the previous study. Interestingly, there were big increases in the number of Orthodox Christians, Muslims, and Hindus, reflecting the significant growth of diversity in the country.

Do these decreasing numbers of Catholics, laity and clergy, escalating downward, mean that the Irish Catholic church is moving towards Celtic oblivion?

Fr. Niall Leahy, a Jesuit priest serving in St. Francis Xavier Church in Dublin does not view the current trend as terminal. “Cultural Catholicism will die out,” he says, but he sees a better replacement on the horizon.

He envisages a new role for priests away from struggling single handedly to meet the community's spiritual and pastoral needs. Instead, he talks about them as catalysts empowering other Christians “to be ministers themselves.”

Fr. Leahy tells about the Sunday evening mass in his church, which is planned by the parish youth and involves them in all parts of the ceremony. He claims that the days when streams of people participated passively in the various devotional practices are gone and that now more young Catholics are proud to claim a sense of agency in their parish community.

He goes on to make a salient point about traditional participation in Mass and similar devotions. He contends

that “the church was over-sacramentalized.” The importance of receiving the Eucharist and showing up at public devotions was emphasized at the expense of other elements of the Christian life. Too often, he claims the people’s inner life of faith was left entirely uncultivated.

The Catholic church has to live down decades of dubious theology. It occupied a gloomy space in Irish life, dominated by fear and punishment. Remember that awful prayer, widely recited, identifying the supplicant as part of “the poor banished children of Eve, moaning and weeping in this valley of tears.”

Contrary to the positive image of the caring father in the New Testament, God was transformed into a distant figure, dishing out punishment and presenting heaven as the end of an obstacle course. The Irish version of Christianity reeked of Manichaeism which divided people into good and evil with terrible consequences for the multitudes in the “evil” population.

All the ancient civilizations propounded creation myths, stories that attempted to explain how the world started. The Judaeo-Christian story centered on Adam and Eve in an idyllic garden located in Eden.

John Milton, a strong Christian believer, explained in the opening lines of his masterpiece poem, “Paradise Lost”: Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit of that forbidden tree, Whose mortal taste brought death into the world, and all our

woe with loss of Eden. God’s punishment in this story for the so-called original sin explains the evil tendencies that led to the pain and suffering in the world. Adam and Eve were to blame for some unnamed sin that marked all humanity, making them, through some twisted logic, more liable to commit evil acts.

Fr. Timothy Corcoran, a Jesuit priest and philosopher, had a big influence on Irish education for half a century after the foundation of the state in 1922. Drawing on the pulpit understanding of original sin, he pointed to the universal attraction of evil and advocated for administering stern punishment for any children stepping out of line. This delirious thinking, endorsed by church and state, led to the outrageous punishment endured by students in most Irish schools until the 1980’s.

The biggest area of concern for the Catholic church, not just in Ireland but throughout the world, centers on sexuality and the roles women are ruled out from playing in the top echelons of the organization. Customs and traditions that applied in past eras are no longer acceptable in our time.

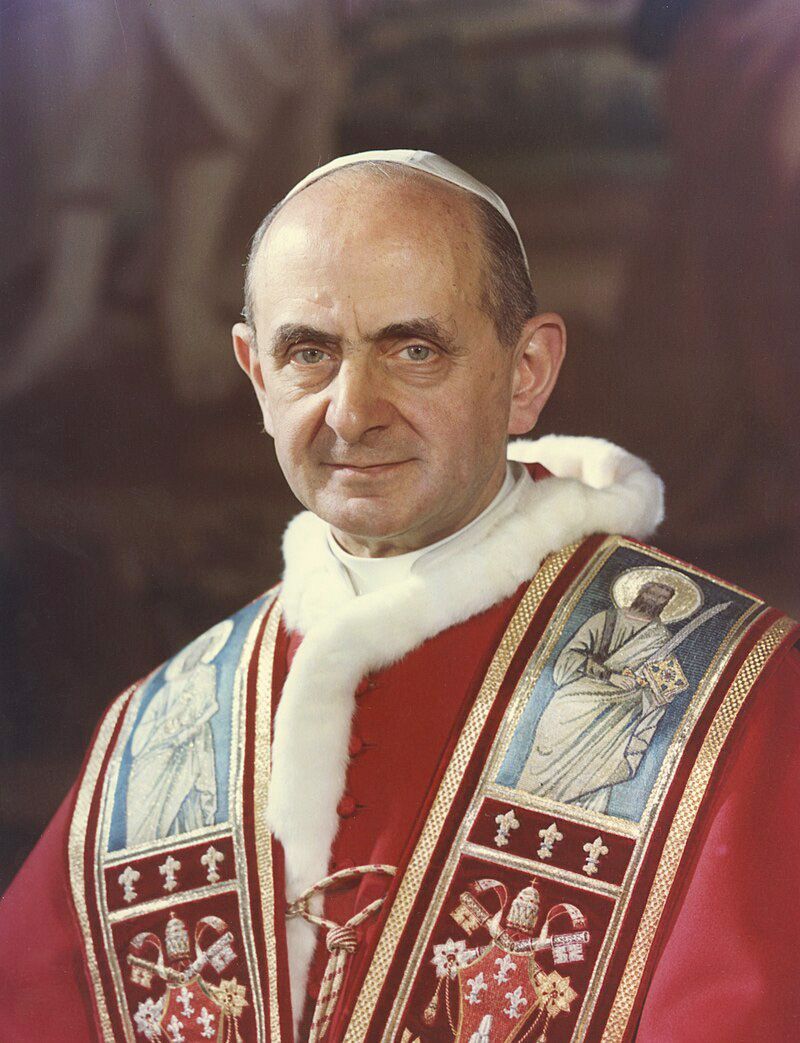

The widespread use of contraceptives to avoid pregnancy is accepted in most countries as a sensible precaution by young couples, married and unmarried. In his disastrous 1968 encyclical, Humanae Vitae, Pope Paul V1 decided to proscribe the use of any medication or device that would prevent pregnancy when married couples engaged in lovemaking.

A clear majority in the Pontifical Commission, appointed by the Vatican to advise him, urged that the church take a more liberal position, but their counsel was disregarded. Paul opted to maintain consistency with Pius X1, his predecessor, from early in the century.

This weak and illogical church mandate, disregarded by the vast majority of Irish people, must be revisited and changed in line with sensible modern thinking.

Pope Francis’ synod will resume in October. The purpose of this international gathering of Catholics is to examine whether the beliefs and customs espoused by the Church are fit for the work of evangelization in our time. We wish them success in their deliberations.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at emustbetalking.com