In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a vibrant Irish Parliamentary Party represented Irish nationalist

aspirations and demands in Westminster. Charles Parnell first provided able and strong leadership, and John Redmond took over at the helm after his demise.

The Third Home Rule Bill passed in 1913 was greeted by massive celebrations in Dublin. Finally, the country would have its own legislature for the first time since Grattan’s Parliament was prorogued in 1800, and that gathering excluded Catholics from serving.

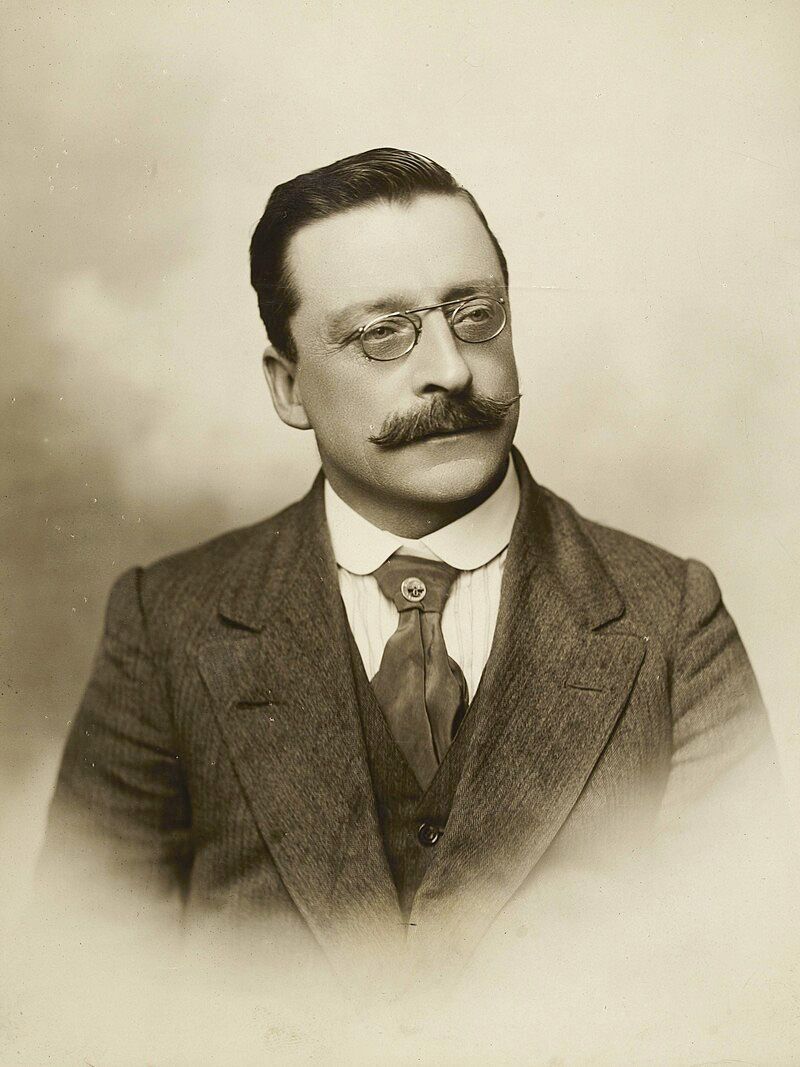

Joseph Fisher. Richard Feetham.

Patrick Pearse, one of the leaders of the Republican Fenian tradition, welcomed Home Rule while warning presciently that if the British reneged on its implementation, there would be “hell to pay.”

A few months before the celebrations in Dublin, Sir Edward Carson, who, along with James Craig, provided the main leadership in the Loyalist community in Northern Ireland, spoke in Craigavon, outside Belfast, before more than 100,000 followers. He left no doubt about his community’s opinion on Home Rule: “the most nefarious conspiracy ever hatched against a free people.”

In response to Unionists' stern opposition to being ruled by any kind of Dublin legislature, the British parliament passed The Government of Ireland in 1920, creating a new parliament in Belfast with the right to pass laws for a bloc of six counties in the northeast. Significantly, no nationalist leader or Catholic prelate was even consulted about this legislation.

John Redmond asserted clearly that nationalists were unalterably opposed to any political division of the island: “The two-nations theory involves the mutilation of the Irish nation, and to us, that is an abomination and a blasphemy.”

Eoin MacNeill. James Craig.

When Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith led the Irish negotiating team to London in October 1921, the nascent six-county statelet already existed. However, the Irish negotiators still argued vainly for a united country. The best they could achieve on this, the thorniest of all the issues they faced, was an agreement to set up a Boundary Commission which would “determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions, the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland.”

Collins, the most respected Republican in the delegation, was wildly off the mark in his assessment of the partition issue. He expected the Boundary Commission to slice off the North-Eastern counties of Tyrone and Fermanagh, as well as parts of Derry, Armagh and Down. This land area constituted almost half of the Northern Ireland territory governed by Stormont and would, in this wishful thinking,

be ceded to the Free State.

Griffith joined him in imagining that the resulting much smaller territory would become non-viable, leading to a united government for the whole island within a dozen or so years. Lloyd George, known for good reason as the "Welsh Wizard," indicated to the Irish negotiators that this new Commission would recommend significant territorial changes that would benefit nationalists. He was simultaneously telling James Craig that he would have an effective veto on any proposed territorial alterations.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was ratified in the Dail in early January 1922. Collins, especially, was very concerned about the savage nightly attacks on Catholics in Belfast and the vicinity of the city. In the summer of 1922, 232 people, nearly all Catholics, were killed in rioting in the North.

Craig and Collins tried to avoid a Boundary Commission by working on proposals that they hoped would advance their mutual agendas. This was a great idea, except Craig’s "not an inch" guiding principle doomed the effort.

The Treaty mandated that the Commission consist of three people: one appointed by each of the two governments in Dublin and Belfast and the third, who would act as chairman, appointed by the British Government.

Craig’s repeated declarations that he would not cede an inch of land, not to mind whole counties, was a serious embarrassment to the Dublin Government whose leaders had promised during the heated debates on the Treaty that the Boundary Commission would lead to significant

transfer of territory to the South.

James Craig’s government reneged on its obligation to appoint one of the three commissioners. This decision required new legislation in Westminster and Dublin to allow the British prime minister to appoint someone to represent the Unionist position.

Joseph Fisher, a distinguished barrister ,was chosen to represent Northern Ireland, and Justice Richard Feetham, a South African-based judge, was drafted in to chair the committee.

In July 1924, the Free State government appointed the Minister for Education, Eoin MacNeill, as its

Commissioner. The committee got down to dealing with its formal mandate on November 7 of that year. It was clear from an early stage that Feetham, supported by Fisher, wanted to maintain the border agreed in the Government of Ireland Act (1920) which created the six-county statelet.

Nationalists were gravely disappointed when the deliberations and results, which recommended no territorial change favoring the South, were leaked to the press in November 1925. In response to the angry reaction among nationalists all over the island, MacNeill resigned from the cabinet while challenging the content of the final report and making it clear that it did not have his approval.

The Boundary Report caused a full-blown crisis in the Free State. Prime Minister Cosgrave went to London to try to salvage something from the debris in a meeting with Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. The effort failed completely. The Minister for External Affairs, Kevin O’Higgins, made a similar trip to Westminster. O'Higgins wanted to internationalize the crisis by involving the League of Nations, a proposal which was also rejected.

After failing to make any progress with the British authorities, Dublin called for the Boundary Commission report to be shelved. That was agreed on all sides, and it finally saw the light of day forty-four years later, in 1969.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com