The name of Charles Scicluna is unlikely to resonate with readers, yet he is playing a major role in deciding whether the Catholic Church should change its regulation on priestly celibacy.

Alone among the main Christian denominations, the Vatican insists that at ordination, its ministers must pledge to remain single and chaste. Scicluna serves as the Archbishop of Malta, and, more importantly, he has Pope Francis’ ear. With advanced qualifications in civil and church law, he was highly regarded by then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who appointed him as the principal investigator of clergy sexual abuse crimes. So, he has heard the stories of the dark side of human nature.

The most coherent institutional argument for ending this celibacy requirement comes from the parishes, which are understaffed and struggling to provide presbytery services comparable to those available as late as fifty years ago. The number of priests in the United States has decreased dramatically from 59,426 in 1965 to 34,344 in 2022.

And today, over one third of these priests are retired and inactive while 95% of diocesan priests were still active in 1965. Talk to Irish people about the huge changes in their home parishes and they will relate about one priest covering the work of what used to engage three or more.

This diminution in clergy numbers represents a huge change – for better or worse – in communities all over Ireland. While the shortage of priests remains the main argument for changing the celibacy mandate, it is not the archbishop’s primary consideration.

He clearly states that his mandate does not include solving the ecclesiastical personnel crisis. Instead, he focuses on the plight of individual priests, the challenges and contradictions in their lives, how these impact the women and children involved, and the inevitable hypocrisy of pastors living double lives.

In an interview with the Times of Malta Scicluna explained that priests involved in long-term intimate relationships with women must be acknowledged as a global phenomenon, and right now, they are faced with an unenviable choice: continue in their romantic relationships while pretending to be honoring their vow of celibacy, or leave their job as a minister in the Roman church.

One of his main concerns points to people living a dual life, which he correctly stresses is mentally unhealthy. Priests, he explained, who pledge to follow a celibate lifestyle in their early twenties “may mature and enter new relationships, including loving a woman.” All very natural, but it places him in an unenviable situation.

A decision from The Vatican of celibacy likely within a few years.

Scicluna worries about the dishonest and fraudulent life that a committed pastor must live while being true to his romantic partner. How does he maintain the integrity of his priestly mission which requires an honest and healthy lifestyle?

The celibacy regulation goes back to the papacy of Gregory V11 (1073-1085), who mandated an end to priests' marriages.

The culture in 11th-century Rome can be fairly described as a miasma of licentiousness and skullduggery, and the image and behavior of the church and its ministers were ensnared in this corruption.

The pope decided that the church needed to uplift the prestige of the priesthood, and he also wanted to obviate claims by priests’ children for monetary or property entitlements.

An additional argument sometimes heard for Gregory’s discipline centers on a belief that a special spiritual grace comes with ordination that sets the priest apart and places him higher even than the angels in heaven in some imaginary celestial pecking order.

Readers who scratch their heads as they try to comprehend this clerical gobbledygook may suspect – with good reason – that clever theologians came up with this rationalization to enhance the priestly status. The absence of a wife and family can undoubtedly be seen as enabling the priest to devote all his energy to his work.

Removing the humdrum everyday demands of raising a family can be viewed as facilitating the priest in his vocation. On the other hand, Christ mainly selected married men as his apostles. The four gospels have nothing to say about celibacy, and Jesus showed no inclination to preach about any sexual issues that somehow have preoccupied popes and prelates since St. Augustine’s time.

In recent years, we have heard loud denunciations of homosexuality, contraceptive use, in vitro fertilization, and medically approved transgender procedures. Fr. Peter Daly, a writer and retired priest in Washington, echoing a theme of Archbishop Scicluna, claims that around 50% of priests, bishops and cardinals are, or have been, involved in sexual relationships of one kind or another. The abuse crisis by a small minority of priests has done immense damage to the church.

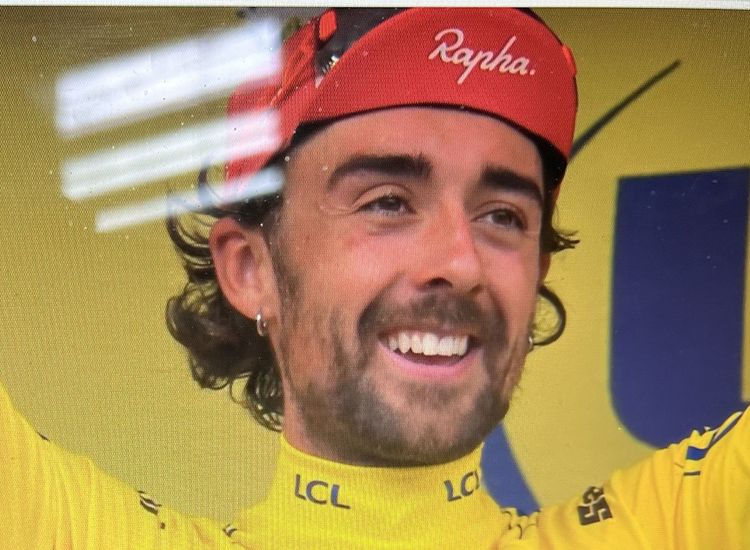

Archbishop Scicluna.

Celibacy certainly played some part in this awful scourge. While only a few bishops and cardinals participated in the sordid abusive behavior, nearly all members of the hierarchy failed to act decisively in dealing with it.

Marie Keenan, the distinguished Irish professor of psychology, makes a very cogent point in reflecting on the crisis: “Abusive priests are not isolated monsters but are products of human and psychological formation that fixated them at an adolescent level of sexual development.”

The question of clerical celibacy engaged Fr. Daniel O’Leary, a distinguished spiritual writer from Rathmore, a village in County Kerry. He authored ten books on spiritual matters and wrote regular columns for the prestigious English weekly Catholic newspaper The Tablet.

He spent most of his life ministering in the diocese of Leeds in England and was in demand as a retreat leader for diocesan priests. Based on his own personal reflections and from listening to his fellow priests, he condemned mandatory celibacy as “a kind of sin, an assault against nature and God’s will.”

He is very clear about the serious damage to a man who is forbidden an intimate relationship with a female partner, cut off from “expressions of healing and the lovely grace of tenderness.”

He also argues that it is very hard for a priest to maintain a sense of personal authenticity while struggling with sexual and emotional drives and pretending to his parishioners that all is well in his life.

The Rathmore spiritual writer’s distress call pleading for change, before his death from cancer, pointed to the inevitable loneliness of men who are compelled to avoid sharing their intimate feelings with a partner who can relate in a loving way to the inevitable ups and downs of life, “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” Charles Scicluna realizes the urgent need for change from Pope Gregory’s rules made a thousand years ago.

I expect a positive response from the Vatican in the next few years.

Gerry O’Shea blogs at wemustbetaking.com