There were a couple of silver linings for Ross Barkan on election night in 2018.

He was with his supporters, for one. “That was definitely great. I enjoyed that,” he said.

And there wasn’t much suspense for the then 28-year-old candidate in the Democratic primary for the State Senate district in South Brooklyn. “The results, in this era especially, come in very quickly and I’m fine with that. I like to know right away,” said the journalist and novelist, whose opponent went on to win in the general election and has been reelected twice since.

I get that need to know, but the mechanics of the process seem to me remote and antiseptic, and not obviously transparent, raised as I was in a country which in some respects has a radically different political culture. I always vote. And there’s no excuse not to; the polling place is in the school beside my apartment building. But I feel a certain emotional detachment when voting. Maybe I’m missing home. So, I set out to ask people about the differences between New York and Ireland.

One fairly stark contrast is the lack of an official election count center in New York that candidates and their supporters might converge upon.

Edwin Wong was with his team when he saw his initial percentage come up on NY1 in 2021. He was one of nine candidates in a Democratic primary for an open council seat in Queens. “We started off in a bar and moved on to a restaurant in Forest Hills,” he recalled. There, they kept track of Board of Elections updates via their smart phones. New York was using the ranked-voting system, and Wong went out after the fourth ballot. It didn’t take long.

“For me, Americans are results-orientated: ‘Tell me what happened, and tell me fast,’” said Barkan, who is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine.

In other systems, like in France and the UK, which both use paper ballots, a broad picture does emerge quite quickly after the polls close, with the details to follow. Both those countries have certain rituals and traditions – like the glass ballot boxes preferred by the French – that make it seem more real.

Ireland, which uses a system of proportional representation and multi-seat districts called constituencies, waits until the next morning to open its ballot boxes. Then the gathered media learns of certain trends via the parties’ combined intelligence-gathering system known as the “tallymen.”

“They’re still mostly men,” said Peter Connell, a historian who has worked as a foot soldier on numerous campaigns for left-wing candidates for over 40 years. “You’re identifying at a granular level where your vote is.”

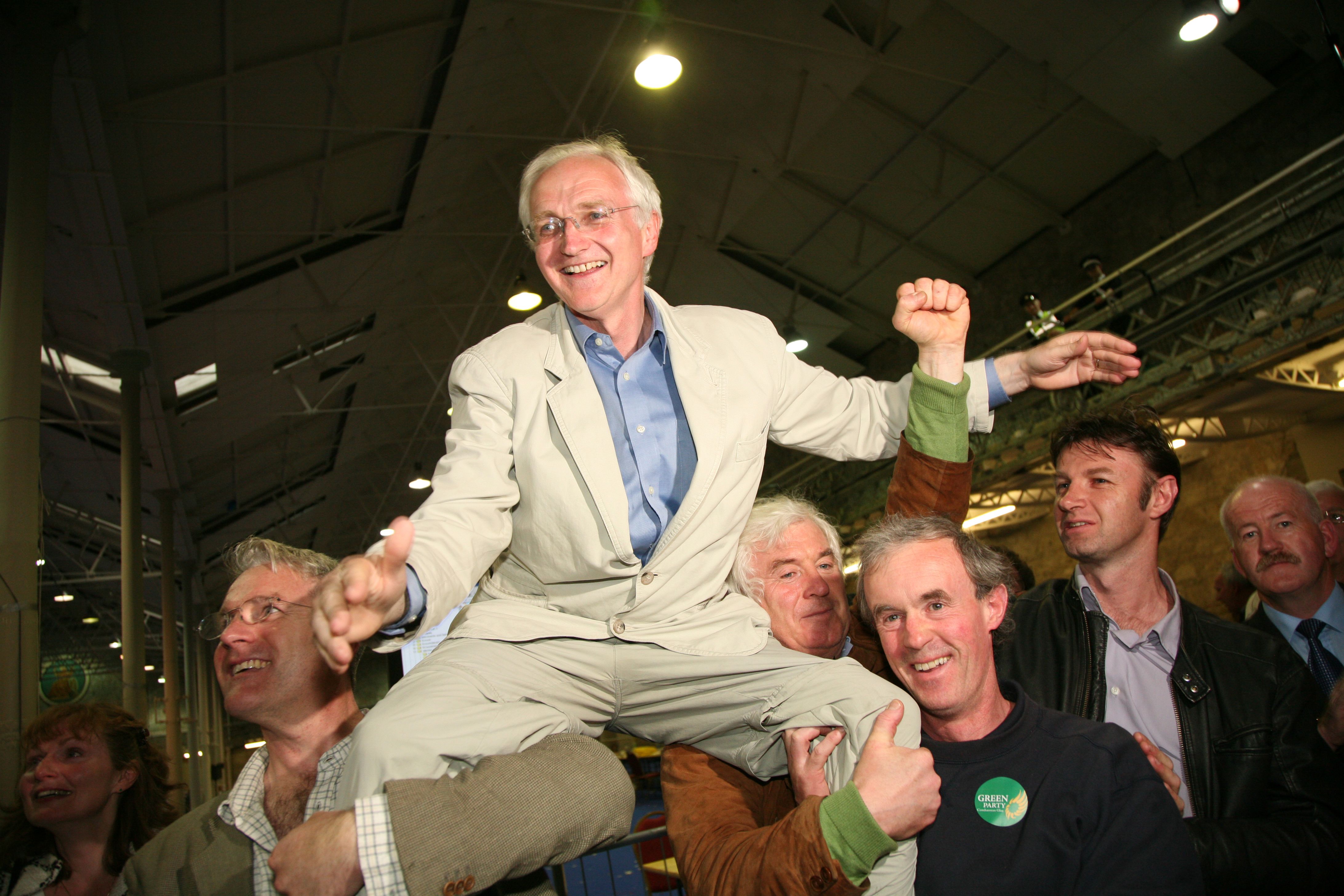

“There’s a big sense of occasion,” said John Gormley, a former government minister and former leader of the environmentalist Green Party. “There’s a sense of camaraderie.”

And yet Gormley, however emotionally he felt connected to the excitement and lore of the count center (where several constituencies’ ballots are counted), at some point became convinced of the need to go to an electronic system. When a member of the 2007-2011 government he developed a policy to do just that; but in the end it wasn’t brought to Cabinet.

“The media were opposed to it, as were a number of academics, and it seems the general public didn’t have the appetite for it either,” he said.

Gormley remembered one of his advisors who went on to work with Google said, “You know they can be hacked?”

He was in opposition when during the 2002 election the then government ran an electronic trial in three constituencies.

“Nora Owen,” was the ex-minister’s two-word summary of that episode.

Connell’s response when reminded of the brief experiment of 22 years ago was identical.

“Nora Owen,” he said.

Three years out of power in 2002, Fine Gael experienced a shellacking, losing 21 of its 54 Dáil deputies.

One of them, Owen, is a grandniece of Michael Collins, the best known of the state’s founders, and certainly the most revered by her party.

The broadcast media, in every single report and update, inevitably focuses at election counts on high-profile casualties and those who appear in jeopardy of becoming one. But it was Deputy Owen’s misfortune that her constituency, Dublin North, covering suburbs, towns and rural areas outside of the city, was one of the three involved in the electronic experiment. For half a day, the only official news was the 53-year-old politician’s ouster.

Owen had shown up at 9 a.m., when the count traditionally begins, but was told that after a number of ballots that she’d been eliminated. It was about 9:20.

“It was like being executed on the spot,” Gormley said.

He believes that if there had been a formal announcement for each ballot, or count, it might have been more palatable.

Connell is not so sure. “The Irish expect that drama to be stretched out over six or seven hours,” he said.

The last time I voted, there was no drama at all. It was late, with about half an hour to go to the close of polls. Usually, you walk down the hill and enter to vote in the school’s basement. A different entrance/exit system was being used at what is officially the ground floor and it confused me. And so, the only voter in the building was for a time lost.

Everyone was pleasant, though – the cleaners, the police officer on duty, the poll workers at the desk handing out the ballots and their colleagues assisting with the process.

Pleasant, that is, in an “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” sort of way.

I’m joking, of course. but it was fun to channel the substantial part of the electorate that subverts the process by refusing to accept the result.

Leading American historian Richard Hofstadter wrote an essay in 1964 entitled “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” and it was included in a collection published soon afterwards. Back then, the Republicans had just dealt with the internal and external threat of the John Birch Society. In the late 1950s, that influential group’s leaders were somewhat divided as to whether President Eisenhower was merely a dupe of the worldwide communist conspiracy or an actual communist.

Professor Sean Wilentz of Princeton University advocated for the re-publication of Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays,” which is what happened in 2020, on the grounds that the situation was worse now. Indeed, the John Birch folks seemed to have taken over one party.

It's true, however, that elections have been stolen in American history. President Johnson trounced Senator Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election, but his nickname “Landslide Lyndon” was ironic, dating to his dubious wafer-thin victory in the U.S. Senate election in Texas in 1948. His illustrious biographer Robert Caro, in “Means of Ascent,” Volume 2 of the “The Years of Lyndon Johnson,” convincingly argues that the election was stolen via the fraudulent misreporting of tallies.

How far might one reasonably go in assuaging people’s concerns? Trump acolytes in a few states are demanding a hand-count of paper ballots, while in others, as Ross Barkan reminded me about New York, objecting to paper when it involves early voting by mail. But if the former is what it takes to preserve rule by consent, then it surely wouldn’t be too high a price to pay?

Peter Connell told me that the North Kildare constituency has an electorate of 80,000, and 50,000 might vote, of which perhaps 300 ballots are spoiled and just a few of those might be contested by individual candidates.

Looking across the Atlantic, he wondered if the United States is just “too vast” for paper ballots.

It is vast, but the decision to radically change the system of vote-counting would only be made by an individual state, and given that the U.K. and France each have about 30 million more citizens than the most populous U.S. state, California, it should be manageable in theory.

Edwin Wong, pictured in MacDonald Park on Queens Boulevard at Forest Hills, is running for reelection to the State Democratic Committee. [Photo by Peter McDermott]

But the good news here is: New York does have a paper system. That’s according to long-time poll-worker B.C. Smith-Ashmall.

“You really can’t mess with it in New York,” she said of the system overall.

“The machines that we have are simply readers,” said Smith-Ashmall.

In New York, we get long pieces of paper, of close-to cardboard quality, which we mark by filling in small oval-shaped spaces (except when it’s a numbering system in ranked-choice elections), and then the ballot papers are scanned.

If the number of ballots doesn’t add up properly at any point, “We go nuts,” she said.

“Nobody leaves until everything is in order. And when I say ‘nobody goes home,’ I mean nobody goes home.

“It’s really strict,” said Smith-Ashmall, who that day was helping her 18-year-old son, the youngest of her four children, navigate the registration system.

The ballots can’t walk. Everything is zip tied. There are all sorts of controls. There are police officers involved in every part of the process, including guarding the ballot boxes as they go back to the Board of Elections.

I have to say I felt much better after speaking with Smith-Ashmall, Barkan and Wong, and I’ll explain that below.

I understand, nevertheless, the great strengths of the Irish system, particularly its communal dimensions.

“It very physical,” Connell said, referring to the carrying and emptying of ballot boxes and the initial sorting of votes.

There are moments when you get close to raw power, as Gormley found out when, in 1983 as a member of the Ecology Society in University College Dublin, he was a volunteer in his first Green Alliance campaign. It was a special or by-election in a constituency near the center of Dublin. At a crucial point in the count proceedings the prime minister, aka the Taoiseach, and leader of the Fianna Fáil party, arrived with his entourage. Gormley could detect the thrill and fear among the Fianna Fáil party faithful as the Napoleonic figure of Charles J. Haughey moved through the crowd.

Later as a young candidate in the city council elections, Gormley found himself for a time ahead in the count of Haughey’s great rival and predecessor and successor as Taoiseach, Garrett FitzGerald of Fine Gael.

Connell remembered the epic 10-day count in 1992 for the last Dail seat in Dublin South Central between Ben Briscoe of Fianna Fáil and Democratic Left’s Eric Byrne, whom he was supporting. “Then the Fianna Fáil heavies came in,” he said, referring to Briscoe’s legal team. “It was like the hanging chads.”

Gormley recalled one vote that was deemed spoiled long ago – someone backed up their No. 1 with a personal message that addressed a senior politician by his first name and ended, “from Cathy, with all my love!”

Connell, who as a college employee helped oversee the election of Trinity’s three members of the Irish Senate (from an electorate comprised of graduates), remembered Senator David Norris being informed why a certain vote was being deemed spoiled: the voter had written, “David, haven’t seen you in ages! Give me a call,” leaving their number. Norris smiled, and said, “Not to worry.” He was way out in front in the count.

In North Kildare, Connell volunteered when he was younger for the recently deceased Labour politician Emmet Stagg and later on worked for the independent left Deputy Catherine Murphy (now with the Social Democrats). “At peak times, there could be 80 tallymen [from the different campaigns] working together,” he said. “There’s great excitement, and huge discussion before each count.”

I’ve never seen anything close to that level of participation in New York City, but I’ve been impressed with the seriousness with which people approach the process.

B.C. Smith-Ashmall’s business card features a quote from Senator Robert Kennedy: “The purpose of life is to contribute in some way to making things better.” She told me, “Politics is my religion, voting my sacrament.” Smith-Ashmall is an active member of the Manhattan chapter of Drinking Liberally, a progressive group that is organized nationally. Its members discuss politics over a few beers, and while a group might invite an electoral candidate to introduce themselves, it won’t ever make an endorsement.

Ross Barkan took a timeout from his promising writing career to run for office and was endorsed by the Daily News and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Now he writes with insight and subtlety about politics and culture for the Times, his Substack newsletter and other outlets.

All three New Yorkers I spoke with had ideas for reform, but Barkan’s was the most far-reaching – scrap the Board of Elections, with its old-style patronage, and put in its place an independent non-partisan bureaucracy.

The partisan swing towards the Democrats, though, has helped the cause of reform in Albany. “I wish I had matching funds when I was running,” he said.

“Fundraising is a challenge,” Edwin Wong agreed, but the matching funds were in place to help him in 2021, and they were much appreciated.

Wong followed his father, the late Thomas D. Wong, into activism in the Asian-American community and the broader community in Queens. The family is Catholic and identified closely with Irish-American Congressman Tom Manton, who was succeeded by a protégé, Joseph Crowley. The younger Wong said both his father, a city worker, and his mother, a teacher, were union members. His father’s facility with various Chinese dialects was put to good use by the city’s Human Resources Administration in its outreach efforts. Upon his retirement, Thomas Wong increased his involvement with the community and the Democratic Organization of Queens County.

Edwin Wong, who works in banking with a particular specialty in commercial lending to small business, was elected to the State Democratic Committee before his run for City Council, which he described as a “very positive experience.” He’s on the campaign trail again in 2024 for the State Democratic Committee.

For me, in the end, it came into view intellectually that the mechanics are just one piece of the puzzle, and they’re just the means. Other parts of the political culture are often far more important. What we need, first of all, are more Barkans, Smith-Ashmalls and Wongs.

Still, one can sympathize with former politician Nora Owen’s response in 2011 when she heard that John Gormley’s plan for electronic voting had been abandoned.

She said, “Good riddance!”

This story was produced as part of the 2024 Elections Reporting Mentorship, organized by the Center for Community Media and funded by the NYC Mayor's Office of Media and Entertainment.