Stained glass artist Michael Healy had “three transformative strokes of good fortune in his life,” according to his biographer David Caron.

But before those, Healy in his late teens took the initiative himself. Despite a background in tenement poverty, he saved funds that allowed him to attend as a parttime student for three years the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art.

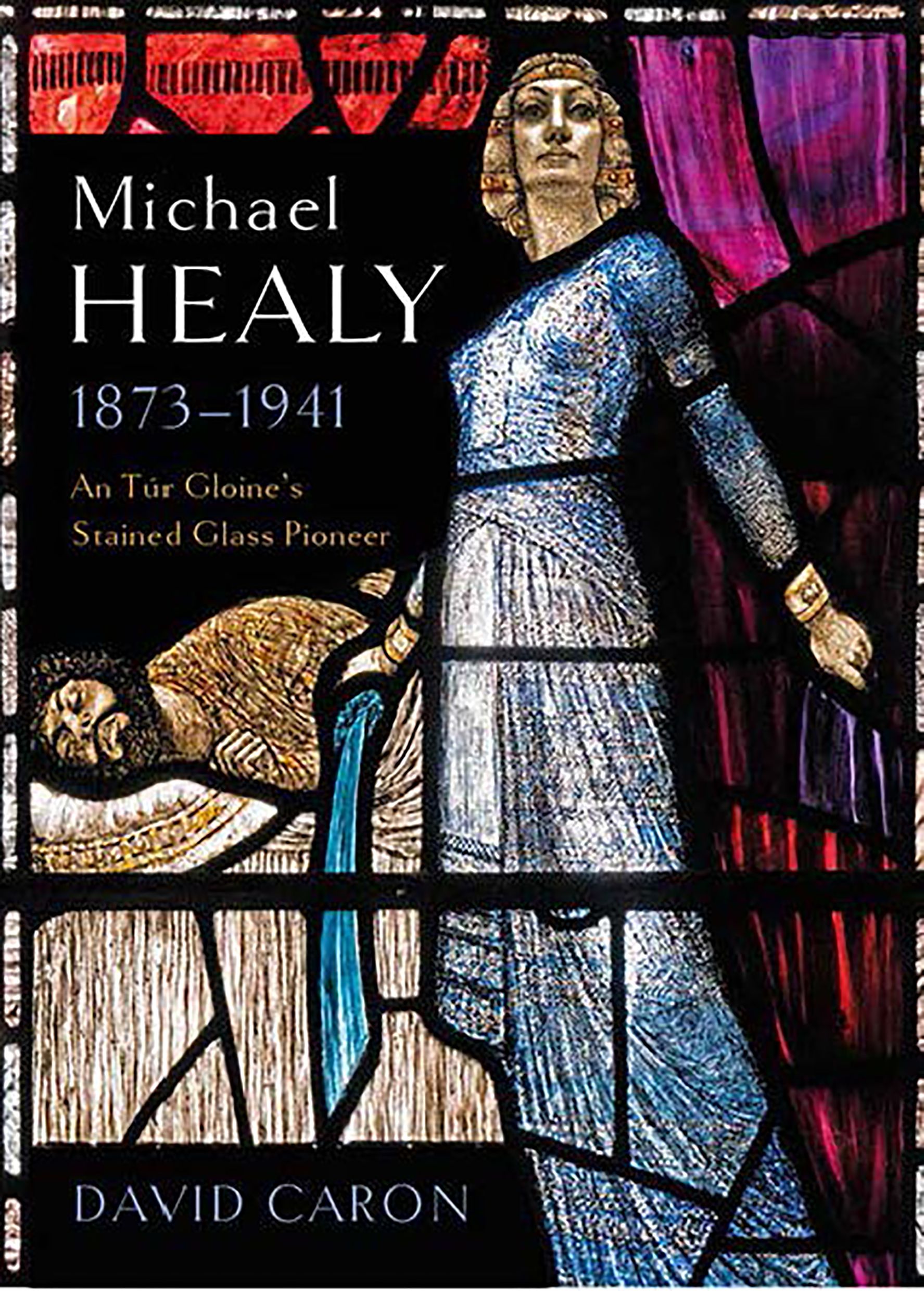

The beautifully illustrated volume “Michael Healy, 1873-1941: An Túr Gloine’s Stained Glass Pioneer” has a map showing the area south of Dublin’s city center where, other than a sojourn abroad, the artist spent his entire life. However, in the earlier period, the addresses are in or around Kevin and Bishop Streets and each is listed by the author as “Tenement flat,” while in later times they’re closer to the South Circular Road and referred to as “Lodgings (with Elizabeth Kelly).”

That first piece of luck happened in Healy’s mid-20s when, Caron writes in the book’s introduction, “he tried to break into the world of commercial illustration and replied to an ad for a new religious magazine, the Irish Rosary. The altruistic editor of the publication, Fr. H.S. Glendon, took him under his wing and arranged for Healy to live in Florence for 18 months, ensuring sufficient ongoing work to make it feasible. Florence opened Michael Healy’s eyes to a world beyond the Dublin slums and in particular to the sublime beauty of Renaissance painting, and from that point onwards the influence of Italian quattrocentro percolated through his work.”

The second was back in Dublin, when “rudderless after a disastrous false start as an art teacher, he was recommended by the sculptor John Hughes to the portrait painter Sarah Purser to join her stained glass enterprise, An Túr Gloine. Healy’s ability to draw the human form, imbue faces with deep characterization, and his profound faith and commitment to religious art – he had previously explored life as a Dominican brother – combined with a capacity to absorb and then to challenge the boundaries of the craft meant that he was an ideal candidate. His entire stained glass career would be spent as one of a handful of artists working at the small stained glass studio in Upper Pembroke Street, Dublin. In his early years at An Túr Gloine Healy also moonlighted as a satirical/political cartoonist for D.P. Moran’s controversial strongly pro-Catholic and nationalistic journal the Leader, a voice for the ‘Irish Ireland’ movement.”

And third, he met the twice-married landlady, Elizabeth Kelly, “who within a few short years became his life partner. In time they would have (in secret) a son to whom he became close, and Michael Healy and Dermuid would regularly go painting and sketching along the Dodder River, the Grand Canal, and in the Dublin mountains. It seems clear that Healy’s relationship with Mrs Kelly was never publicly acknowledged and had it been revealed – particularly the revelation that he had fathered a child with a married woman – it could have abruptly terminated his stained glass career given that virtually all An Túr Gloine’s clients were clergy, and Ireland in the early decades of the 20th century was conservative, censorious and unforgiving.”

Caron told us, “The book charts Healy’s life and stained glass career, and features images of all his principal windows in Ireland, Britain, the United States and elsewhere – windows that convey everything from austere majesty to tender humanity, often revelling in beguiling narrative detail. In his spare time Healy surreptitiously recorded Dubliners going about their daily business, producing many, many hundreds of charming, rapidly executed pencil and watercolour images which collectively form a homage to the citizens of the city he loved.”

Leading art historian and critic Thomas McGreevy said upon Healy’s death that he was “the pioneer artist of the modern Irish stained glass movement.”

Caron said the artist, who was “ahead of Harry Clarke, Wilhelmina Geddes and Evie Hone, established the bar for artistic and technical excellence in this exacting craft” during his almost 40 years with An Túr Gloine.

There are two obvious reasons why he hasn’t been better known than Clarke, for instance, who was his junior by a decade and half and whom he outlived by 10 years. One was his “innately reticent and often moody personality;” the reclusive Healy never developed large networks of friends and contacts.

The other is that there are few examples of the Dubliner’s work in the capital. It is often in quite remote places – places, like Bridge a Crinn, Co. Louth, that most people have never heard of.

Caron, the retired head of the Department of Visual Communication at the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, recommends that to view a comprehensive collection of Healy’s work, one might visit St. Brendan’s cathedral in Loughrea, Co. Galway.

David Caron

Date of birth: May 16, 1960

Place of birth: Dublin

Residence: Dublin City

Published works: “Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass” (co-compiler of first edition in 1988, and editor and principal contributor of the revised and expanded edition in 2021), many articles on various aspects of Irish stained glass over the years, mainly for the quarterly journal, Irish Arts Review.

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

I usually start before 8 a.m. and continue until approximately 4 p.m., taking a few breaks along the way, maybe including a walk along the banks of the Grand Canal which I live adjacent to – it’s a great way to clear the head, get a bit of exercise, and enjoy some fresh air. I was fortunate when working on my book on Michael Healy as I had already undertaken most of the research for it when doing my PhD at Trinity College Dublin in the 1980s and ‘90s. I subsequently donated all my research to the National Irish Visual Arts Library but when it was closed during Covid for a protracted period they kindly permitted me to borrow it back so I had all the research, carefully organized, at my fingertips. So for about 18 months I worked away at home, just me and my laptop, surrounded with archival boxes full of folders. It was a very productive and satisfying period of my life, though ultimately rather solitary, too, of course.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Be disciplined and determined!

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

I’ll select one: Nicola Gordon Bowe’s “Life and Work of Harry Clarke” is a book I found myself constantly referring back to when writing my book on his contemporary, Michael Healy. Her prose is excellent and reminded me of her stimulating lectures I had the pleasure of attending when I was an undergraduate at art school.

What book are you currently reading?

I was in Venice earlier this year for the first time and am reliving the experience by reading Donna Leon’s crime thriller, “Uniform Justice”; very evocative of this magical city though happily I experienced it without any murders, unlike in her book!

Is there a book you wish you had written?

No single one comes to mind.

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

“Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” by John Berendt surprised me with the seemingly effortless way he could weave real events with imagined dialogue to create a mesmerising account of sensational events which took place in 1980s Savannah, a city I subsequently had the pleasure of visiting.

If you could meet one author, living or dead, who would it be?

Well as a Dubliner, James Joyce would be a fascinating person to meet but I feel I would probably be intimidated by his both personality and intellect.

What book changed your life?

I don’t think I can choose just one, but many books that are written from the heart about personal experience have the potential to be transformative.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

I love hiking in the wilderness of County Wicklow as it is so accessible from Dublin yet it is a world apart.