A unique film on the life of an Irish woman revolutionary will make its premiere at the CraicFest on Friday, March 8, at 7 30 p.m., at the Village East Cinema. The film, “Rebel Wife,” relates the “untold story of poet, organizer, and revolutionary Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa a woman whose courage, planning, and determination helped free Ireland.” Williams Cole, great-grandson of Mary Jane and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, made the film as a companion to his “Rebel Rossa,” a 2016, film about the centenary of Rossa’s death and famous 1915 funeral in Glasnevin Cemetery, which played a key role in instigating the Easter Rising of 1916.

Cole grew up with a strong sense of the vital role Mary Jane played in the fight for Irish freedom, but she was overshadowed by the larger-than-life figure of her husband, who became a celebrity in 1865 when the British government sentenced him to life in prison for treason. Cole called the project a labor of love “fueled also by a strong belief that the story of women in history has long been erased, sidelined, and unacknowledged.”

Mary O'Donovan Rossa.

The documentary tells the amazing story of how 19-year-old Mary Jane Irwin from Clonakilty, Co. Cork married the 32-year-old Rossa against her parents’ wishes. At age 20 her husband was imprisoned. Amazingly, leaving her infant in Ireland, Mary Jane came on her own to America at a time when women had few rights and circumscribed roles in public life. Taking public speaking lessons, she became a barnstorming public speaker, touring the United States and Canada for two years, reading her poetry and highlighting the suffering of imprisoned Irish revolutionaries like her husband. Calling herself the “prison widow” she not only became a celebrity but also raised huge amounts of money, much of which she sent back to Ireland to provide for the families of incarcerated patriots. She also highlighted the torture that her husband and other incarcerated Irish revolutionaries were suffering. She followed up her American tour with a speaking tour In Ireland, all the while hoping that the publicity her speeches created would help free her husband and other jailed Irish revolutionaries.

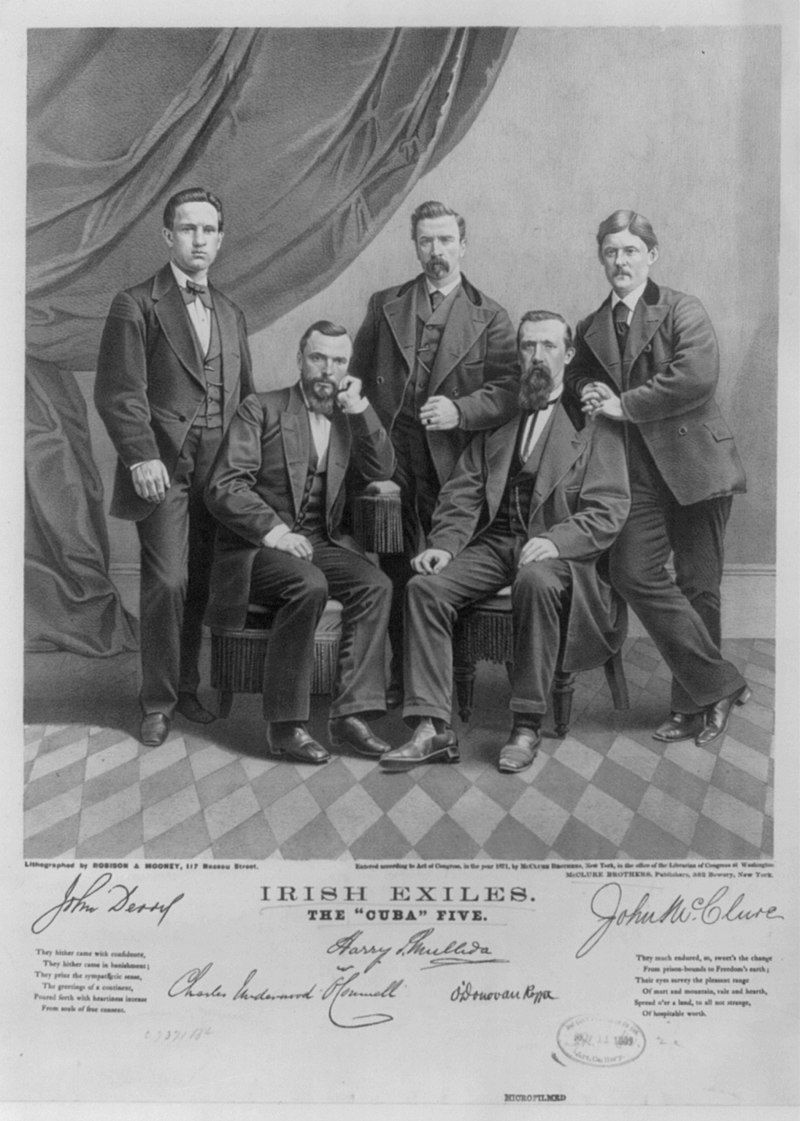

From left, John Devoy, Charles O’Connell, Henry Mullady, Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa and John McClure were Fenian prisoners who under general amnesty were released by the British to America on Jan. 5, 1871, and were shipped together aboard the “Cuba.” [Library of Congress]

The film documents how the British government withheld letters the couple had written to each other while O’Donovan Rossa was imprisoned, increasing the strain on an already difficult relationship. It also relates how her publicity campaign finally led to her being allowed to see him in prison and to his eventual exile by the British government.

Her husband arrived in New York and instantaneously was greeted as a hero. Mary Jane quickly faded into the background. She would bear him 13 children, only seven of whom would live to become adults. O’Rossa tried many business ventures to support his family. However, he became volatile, suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome, and had little business success. Mary Jane became a rock of stability, which the increasingly unstable Rossa relied on.

Their marriage lasted over a half-century. At the end of his life, Rossa was an impoverished, sick man. He had always wanted his body returned to Ireland for burial and initially, the family had planned to send his it back to Cork, however, she understood that Rossa’s funeral could be a huge event and one that could help spark the flame of revolution. Mary Jane decided against the wishes of her husband that the funeral would take place in Dublin. Working closely together with Fenian Thomas Clarke, she agreed that her husband would be buried with great fanfare in the Republican plot in Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery. Mary Jane and her daughter traveled back with the body to Ireland and she was present when Padraig Pearse made his immortal funeral speech. The funeral and Pearse’s oration became, as she intended, a catalyst for revolution in Ireland.

Patrick Pearse.

She was deeply grieved when many of the same people who were involved in her husband’s funeral were shot for their part in the Easter Rising. She died a few months after the rising in 1916 and was buried in Staten Island, not next to her husband in Ireland. Sadly, though she had devoted her life to Irish freedom, her death drew scant coverage in the newspapers.

All documentaries present challenges and Cole said making one about a 19th Century woman of whom there were no moving images and only a few photographs, presented quite a challenge. Unlike his previous film, which included events from the 2015 centenary, there were no real events he could include in his film. Luckily, he had a lot of material from the family archive and passionate individuals like researcher Judy Campbell - who had uncovered a lot of material related to Mary Jane. Cole’s film is important because it looks at the struggle for Irish independence from a female point-of-view and reminds the viewer that women also played a vital role in the fight for Irish freedom. “Rebel Wife” made its Irish debut at the IndieCork Film Festival in December and RTE will also air it. A question-and-answer session with Cole will take place after the screening as part of its debut at the Craic fest.

It is fitting that the film will make its American debut during Women’s History Month. The film is part of a wider belated recognition of the role of Irish women in the fight for Irish independence. Thomas Clarke for many years was supported by his wife Kathleen and the first purely political strike in American history was organized by Irish women in New York against British ships. We need more stories like Cole’s brilliant film.