Three legions of the Roman military – the 17th, 18th and 19th – slowly made their way towards their winter encampment near Cologne on the Rhine in September 9 A.D. It had been quiet during the summer and that wouldn’t change as soldiers from the south of Europe didn’t much like being out and about during the harsh weather of Germania’s dark months.

The force led by the Emperor Augustus-appointed governor Publius Quinctilius Varus had, first, to deal with a rebellion some distance away. But the diversion was a trap – the threat was rather closer, and far larger than believed.

Rome had long been intent on creating a new province in Germania between the Rhine and the Elbe, a dubious undertaking in an area that was mostly covered with forest, had little to give in terms of tribute and was populated by a variety of tribal groups, ranging from the somewhat friendly to the openly hostile.

The Battle of Teutoburg Forest was rediscovered, one could say, just as a German cultural identity began to take shape four centuries ago, but nobody could tell where it had happened. When nationalism took root in the 19th century, as it did in most of Europe, the quest to find the battle site intensified.

Theodor Mommsen, liberal politician, critic of antisemitism, and the earliest-born winner of a Nobel Prize (1817; he won for Literature in 1903) had an idea. He had been familiar with the remote hamlet of Kalkriese, near Osnabrück (a town in Lower Saxony famous as the birthplace of “All Quiet on the Western Front” author Erich-Maria Remarque). He suggested that the Kalkriese Gap, with the 160-meter hill on the south side and the Great Moor on the north, might’ve provided the perfect trap in which guerillas could engage regular troops.

Indeed, that’s apparently what went down over three or four rain-drenched days in mid-September, 9 A.D. – for we have our battlefield, thanks to a process of archeological discovery begun 35 years ago by a metal-detector enthusiast.

Arminius, a 27-year-old Roman-trained soldier, had put together a makeshift coalition of his own tribe, the Cherusci, and five others, before luring Varus’s forces into the Kalkriese Gap, which has been compared to a lobster pot – the three legions could get in easily enough, but they couldn’t get out. Best conservative estimates put the imperial death toll at 14,000 troops

Back in Rome, a distraught 72-year-old Augustus focused his rage on the now-dead trusted insider he’d sent to govern Germania. “Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!” the emperor reportedly screamed. He only had 25 and losing three of them in a single engagement was a massive psychological blow. The Roman military would never again use the legion numbers 17, 18 or 19.

“Everywhere in Germany, the local gentry was putting it in their own backyard,” said the late Tony Clunn, in the café of the state-of-the-art museum at Kalkriese in 2008. He had been a major in the British army’s Armored Field Ambulance when posted to West Germany in 1987, and a detectorist in his spare time with a particular interest in the Roman period. He checked in with regional state archeologist Professor Wolfgang Schlüter, who told him that that corner of the world wasn’t known for Roman finds, but he was nonetheless sympathetic to the dismissed theory of the long-dead Nobel laureate Mommsen.

So Clunn went on a search, and one Saturday afternoon, accompanied by his children and the family dog, he uncovered scattered Roman coins, all pre-9 A.D. He continued his work at Kalkriese over the next year or so with Schlüter advising and guiding him. Eventually he found slingshot, the first militaria.

The center of Varusschlacht Museum Und Park Kalkriese, Germany.

The U.S. army still discusses this attack as a textbook example of asymmetric warfare, in which a technologically inferior force overcomes a stronger one. The extent to which the Battle of Teutoburg, or Varus Battle, shaped history in the much longer term has been debated by historians; but it’s certainly true that while there were two provinces with Germania in their title, the third planned for east of the Rhine never happened.

The Rhine would remain on the frontier between the Germanic world and the one where Romance languages predominated. The most famous place in today’s Germany founded by Rome was to get its permanent name in 51 A.D., when it became Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium. In fact, except in official Latin, it would simply be referred to as “Colonia,” or these days Cologne.

‘Prize of war’

The term “colonia” is not foreign to Americans. For example, after Puerto Ricans became citizens under the Jones Act of 1917, some migrants established “colonias” in New York City ahead of becoming a fully-fledged community. And Puerto Rico itself had become an American colony following the U.S. attack on it 125 summers ago.

Many say it still is. Denver-based writer Alberto C. Medina is president of Boricuas Unidos en la Diáspora, an organization of Puerto Ricans in the U.S. who advocates for decolonization. In a New Republic essay two months ago, Medina wrote about the “ignominious 125th anniversary.”

He said, “On July 25, 1898, U.S. troops invaded Puerto Rico as part of the Spanish-American War. They won a swift victory and, by the end of the year, the U.S. had taken the island as a prize of war, ending 400 years of Spanish rule of the island. At the time, many Puerto Ricans really did, as the saying goes, greet Americans as liberators. Most expected that, in short order, the U.S. would either incorporate Puerto Rico or grant it independence. Instead, Puerto Ricans traded one colonial master for another, and the great-great-grandchildren of those who hoped for statehood or sovereignty are still waiting to this day.”

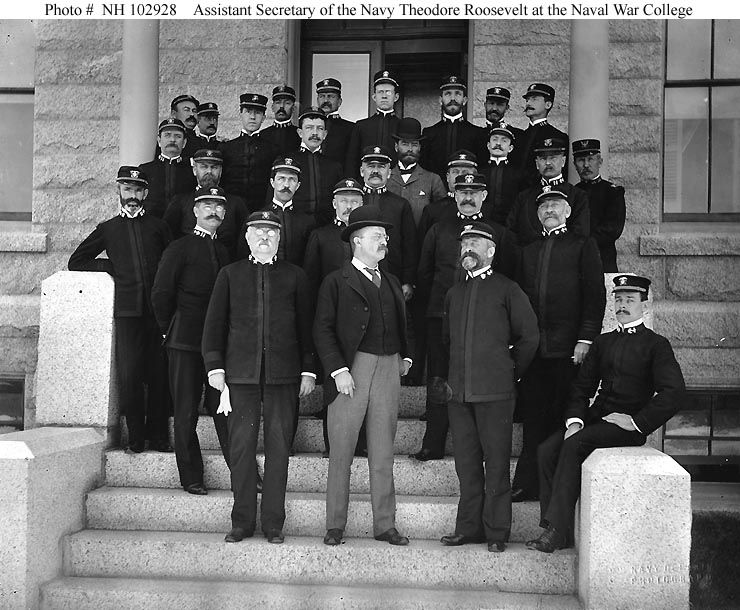

Puerto Rico was acquired during the late 19th century burst of enthusiasm for American adventurism overseas, which today we still tend to associate with future President Theodore Roosevelt, a combatant in the Spanish-American War.

There were skeptics, naturally. Writer Mark Twain was a critic of American imperialism, while prominent Missouri lawyer Frank Walsh seems to have been a rare advocate for Irish independence who took issue with the United States’ conquest of other lands. Such people made similar arguments to those being advanced by Medina and others in the 21st century.

He wrote in the New Republic: “It’s bad enough that the U.S., which began its national history by freeing itself from an empire, has now spent more than half that history (the latter half, to boot) with colonial possessions of its own. Worse still is that, despite decades of evidence about the immoral and undemocratic nature of the island’s status, many Americans still refuse to acknowledge that Puerto Rico is a colony at all.”

That has always been one crucial element to the subordinate relationship, as George Orwell, the British socialist critic of his country’s empire, argued -- the pretense that that relationship doesn’t exist.

Medina said, “The U.S. ruled Puerto Rico directly, through an appointed governor, for half a century. In the late 1940s, when the emerging post–World War II global order started to frown upon such rank imperialism, the U.S. allowed Puerto Ricans to elect our own governor and start drafting a Constitution. It was ratified in 1952 and officially proclaimed as the law of the land on July 25 of that year.

“That Constitution created the ‘Estado Libre Asociado’ of Puerto Rico, which has long been nonsensically translated into English as ‘Commonwealth.’ It signaled, the theory went, the start of a different political relationship between the U.S. and Puerto Rico, in which the latter enjoyed a large measure of self-rule. But it was clear from the start that the Puerto Rican Constitution merely put lipstick on a colonial pig.”

That July 25 is the second reason that the date is a “notorious” one in Puerto Rican history, in Medina’s telling. The third was the incident of July 25, 1978, in which, “Puerto Rican police entrapped two young pro-independence activists and shot them dead. Subsequent investigations, including by the Justice Department, uncovered a plot at the highest levels of the pro-statehood government to kill the young men and cover up the shooting.”

He added, “The Cerro Maravilla murders joined a too-long list of attacks on the Puerto Rican independence movement that includes the 1937 Ponce Massacre of 17 peaceful protesters; the imprisonment—and, likely, torture—of pro-independence leader (and Harvard Law graduate) Pedro Albizu Campos; and the decades-long FBI surveillance of pro-independence activists and supporters that produced more than 1.5 million pages of counterintelligence files, some of it as recent as the 1990s.”

This history, “all but unknown to most Americans, is a grave moral stain on the U.S. government,” Medina wrote.

However, he suggested in his New Republic essay that the political and electoral dynamics are changing in Puerto Rico, reporting that in 2020, “the Puerto Rican Independence Party’s gubernatorial candidate [Juan Dalmau, its co-secretary general] got 14 percent of the vote. Another party’s openly pro-independence candidate also got 14 percent. (For context, the current pro-statehood governor won a six-way race with just 33 percent of the vote.) Those two parties are now forging a coalition ahead of the 2024 election that could result, for the first time ever, in a pro-independence leader ruling Puerto Rico.”

Juan Dalmau was the Puerto Rican Independence Party’s candidate for governor in 2020.

He continued, “Americans who may support statehood for Puerto Rico would do well to reflect on whether it could ever achieve a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate when Republicans are hostile to it and Democrats are divided on it—or whether their support amounts to waiting for Godot while Puerto Ricans remain colonial subjects.

“They should perhaps consider joining the tide of growing support for a sovereign status, if only because it’s the only other alternative,” Medina said.

Decline but not fall

After visiting with Clunn at Kalkriese, I spoke with some authors for a long-form piece about the battle (which was published in an online magazine that later closed down). One of those was Peter Heather, author of “The Fall the Roman Empire” (2005), and another was Christian Pantle, a Munich-based journalist who had written a recent book about the Varus Battle through a German post-nationalist lens. And I drew upon textual sources ancient and modern – including Adrian Murdoch’s book “Rome’s Greatest Defeat,” considered the best account available.

While living commentators might disagree on what lessons that can be drawn from individual situations, they are agreed that studying the empires of the ancient world and looking for parallels with our own era can be a fruitful exercise

Several key themes and issues come up time and again. One is epitomized by the line from “The Life of Brian,” the 1979 Monty Python film set in biblical times: “What have the Romans ever done for us?” People like Flavus, Arminius’s brother who remained a loyal member of the imperial army, might have said, “Quite a lot, actually.” Flavus continued his rise after the battle and fought under leading general Germanicus, while Arminius was to be a fatal casualty of internal Cherusci intrigue at age about 37.

For King’s College London’s Heather, an expert on late antiquity and the empire’s relationship with “barbarian” peoples, someone like Arminius would not have seriously threatened Rome’s power in northern Europe. If anything, his rebellion provided a useful, if expensive “reality check.”

The brilliant Roman general Drusus, brother to Tiberius, the emperor’s ultimate successor, had done a lot of the conquering of that part of the world, but he accidentally fell from his horse in 9 B.C. and died soon afterwards. Little progress was made in the almost two decades leading up to the Teutoburg Forest calamity. His son Germanicus (the grandson of Mark Antony and brother and father of future emperors Claudius and Caligula) did the revenge tour in 14-16 A.D., meting out reprisals on those responsible for Teutoburg Forest and their civilian populations. And over the next few centuries, Rome always found a way to show who was boss.

In time, though, the periphery becomes stronger, in Heather’s view. Arminius’s Cherusci were absorbed into the Saxons, which invaded post-Roman Britain along with the Angles, while the barbarians in general were to undermine Rome’s dominance.

Heather has co-authored very recently, “Why Empires Fall: Rome, America and the Future of the West.” His collaborator John Rapley, a Cambridge University economist, wrote an opinion piece in the New York Times on Sept. 4 entitled “America Is an Empire in Decline. That Doesn’t Mean It Has to Fall.”

He wrote, “At the famous Bretton Woods Conference, the United States developed an international trading and financial system that functioned in practice as an imperial economy, disproportionately steering the fruits of global growth to the citizens of the West. Alongside, America created NATO to provide a security umbrella for its allies and organizations such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to forge common policies.” (That would’ve, of course, made Tony Clunn a soldier of that empire when he discovered the battlefield at Kalkriese.)

Rapley’s interchangeable use of the terms “America” and “the West” might be a little problematic, but he had really interesting things to say about topics, for instance, like the America First position and the West’s relationship with China.

The author suggested that America “can, with the right choices, look forward to a future in which it remains the world’s pre-eminent nation.”

I mention his piece here, though, mostly because Rapley acknowledged straight away that the term “global empire” is a difficult one for this country’s self-image, and later he said, “To call America an empire is admittedly to court controversy or at least confusion. After all, the United States claims dominion over no countries and even prodded its allies to renounce their colonies.”

Many Puerto Ricans might beg to differ with the idea that America has no colonies. Quite a few Americans, too. The long-time U.S. Representative Steny Hoyer, a Democrat from Maryland, asked when he proposed the Puerto Rico Status Act in 2022: “Does the United States want to be a colonial power? I hope the answer to that is ‘no.’ Emphatic no. That is not a political issue. That is a principle issue. That’s an issue of what our country is about.”

And in the less repressive atmosphere of the 21st century, tired of what Alberto C. Medina called its “waiting for Godot” politics, Puerto Rico might increasingly demand that its anomalous situation be put right, one way or another.