It is a truism accepted in most cultures that children thrive in a supportive family and in a community where they feel valued and encouraged. The old Irish adage “mol an oige agus tiocfaidh se” (praise young people and they will blossom) contains important wisdom from the ancient Celts.

However, for most of the 20th century in Ireland, this advice, in Shakespeare’s words, was “more honored in the breach than in the observance.”

There were two important considerations that underpinned Irish child-rearing practices throughout most of the last century. First, contraceptives were not available until late in the 1980s, mainly because of opposition by the Catholic Church. So big families were an important feature of Irish life.

Think of parents in a crowded house rearing eight or ten kids and obliged to maintain order in the family. Anyone who stepped out of line would likely be slapped or otherwise physically reprimanded. According to common parlance, the ideal child should be seen but not heard – a terrible child-rearing dictum.

This unfortunate approach extended to Irish national and secondary schools where teachers, representing official state policy, took pride in their power to wallop children for learning or behavioral problems.

Surprisingly, the humane and child-centered ideas of Patrick Pearse, revered leader of the 1916 Revolution and a dedicated and idealistic educator, were disregarded, except by an occasional teacher who rejected the neanderthal thinking that maintaining classroom discipline required beating pupils with a cane.

The second contributor to this cultural approval for maltreating kids came from a Jesuit priest and leading church intellectual named Timothy Corcoran who had a huge influence on education in the early decades after Irish independence in 1922.

Drawing on his understanding of the doctrine of original sin, he concluded that, while baptism went some way to expunging the effects of Adam’s transgression, it left a strong tendency towards negative behavior. This delirious logic provided the justification for the physical punishment administered to children at home and in school.

Pearse’s humane child-centered education philosophy was sidelined in favor of a second-rate theologian promoting shallow rumination about the Book of Genesis. It took fifty years for the Irish government to abandon the idea that children should be beaten as part of their education.

The Ryan Commission was set up in 1999 with a remit to report on all forms of child abuse in Irish institutions for children. Most of the allegations it investigated related to happenings in sixty “Reformatory and Industrial Schools” operated by Catholic Church orders, and funded and supervised by the Irish Department of Education.

The report, published in 2009, asserted that the commission members had seen abundant evidence that the entire system in these schools treated the children as prison inmates and slaves instead of young people with rights and human potential. It further claimed that the religious authorities in those schools encouraged ritual beatings of the poor kids in their care.

The Department of Education inspectors, whose work assignment included ensuring humane treatment for the unfortunate boys, failed completely to do their job. The children had nobody on their side as they were terrorized into submission. Ironically, children in similar schools in Northern Ireland, run by the same religious orders, fared better because the British inspectorate insisted on somewhat higher standards.

Among the more extreme allegations of abuse were naked flogging of the pupils and frequent forced participation in oral sex. After reviewing the commission’s evidence, the Guardian newspaper described the abuse level as “the stuff of nightmares.”

How does one explain the despicable behavior of clerics who were trusted to care for vulnerable boys? All the brothers and priests involved spent more than a year in novitiate training designed to instill the basic Christian values clearly set forth in the New Testament. Community prayers and Mass were part of the daily regimen in all these so-called schools.

In truth, these publicly funded institutions were cauldrons of vice and misery. Initially, Irish people were shocked by the Ryan Report, but as the multiple stories of predation were authenticated and bolstered by accusations of similar abusive behavior in many regular schools and parishes a massive decline in church attendance resulted.

Bishops’ pronouncements, once given great credence, were now viewed with a gimlet eye, conveying a cynical incredulity when responding to moral declarations by members of the hierarchy. From being the last bastion of traditional Catholicism, Ireland now fits comfortably as part of post-Christian Europe.

The members of the Ryan Commission were precluded from examining the behavior in Magdalene laundries because of legal constraints imposed by the government. However, in 2013, the McAleese Report shed light on these demeaning places where girls were sent.

These institutions, run by nuns, were punitive profit-making places concentrating on needlework and laundry services. The workers were all unpaid and not recorded for the mandatory government insurance stamp.

Four orders of nuns assumed control of these “homes:” the Sisters of Mercy, the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity, the Good Shepherd Sisters and the Sisters of Charity. Despite these high-sounding and unctuous religious titles, they operated places of secrecy, humiliation and shame.

There were ten different Magdalene houses throughout Ireland and the McAleese Report estimates that they housed approximately 10,000 women from the foundation of the state in 1922 until the last one was closed in 1996. The women who were confined there were viewed as the detritus of Irish society.

The McAleese Report points to the perception that many were “promiscuous” or were unmarried mothers. Others ended up in one of these places because they were considered a massive burden on their destitute families, while girls who were sexually abused, or were viewed as feisty females by local priests or police, also found an open door in one of these “homes.”

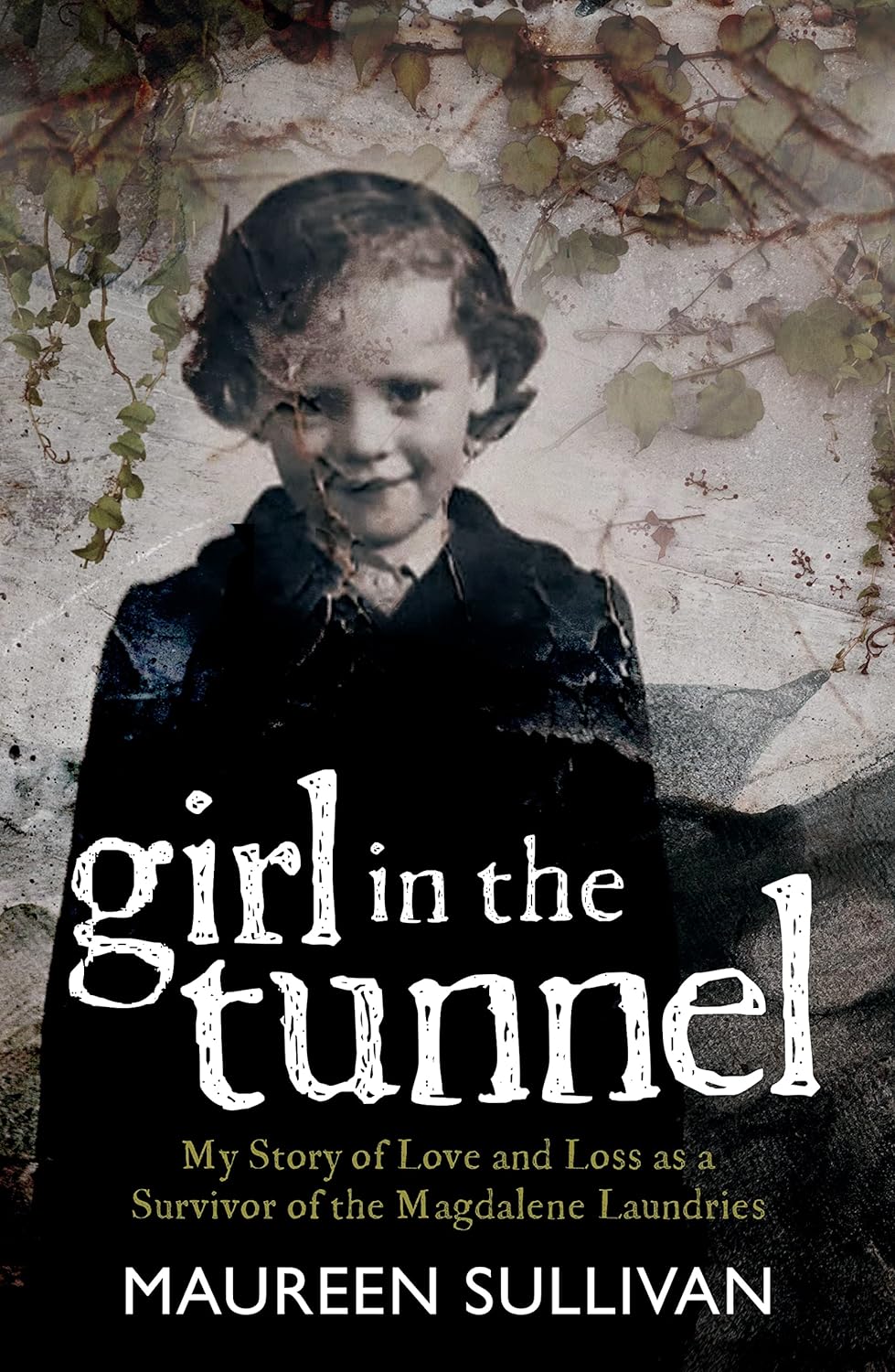

I just finished reading the saddest book I have ever read named “Girl in the Tunnel” by a wonderful woman from County Carlow named Maureen Sullivan.

She was born in Bennekerry, a townland in that county and attended the local school there. Her father carrying the famous name of John L Sullivan died a few months before Maureen arrived. Her mother married again two years later, this time to a lame pig-jobber from Carlow town named Marty Murphy.

Murphy was a disastrous human being who regularly beat his stepdaughter and somewhere around her 11th birthday he started sexually molesting her. A nun in her local school, Sr. Cecilia, observed her unkempt appearance and her unhappy demeanor. She called in the local parish priest, and he decided to move her to St. Mary’s in New Ross, County Wexford.

Maureen was around twelve years old - and the time frame is the early sixties. Sr. Cecilia had told her she would be going to school in her new surroundings and indeed there was a boarding school, St. Aidan’s, nearby. The Good Shepherd Sisters (what a misnomer) informed her that she was no longer Maureen but had a new name, Frances.

She asked about school and how she could get there. She was told in a very harsh and unbending way by the nuns that she would be trained in laundry work and would be expected to work long hours like all the older women there.

This is the beginning of Maureen’s horrific story in Magdalene settings. She never again saw a classroom. Two years later, at age 13, she was moved to the care of the Sisters of Mercy in Athy, County Kildare, where she spent another two years of slavery in the laundry service. From there, at around age 15, and now well into the 1960s, she was moved to the care of the Sisters of Charity in their asylum for the blind in Merrion Road in Dublin.

The conditions were better than in the previous two hellholes, but she was still working a full week, morning to night, with no payment, and worse, still no education.

Now living in her own house in Carlow, I hope Maureen writes another book.