On the road to Independence, the Uber driver told me that his grandfather, a dedicated smoker, lived to an advanced age.

“He was over 90,” he said.

I nod along in such conversations. On this occasion, I was thinking, “If this guy wants to have the odd cigarette past 60, good luck to him. It’s none of my business.”

The strange thing is that a powerful counter example had presented itself by the time I stepped out into the air ready for the return trip to Kansas City.

It was 4:30, dark and drizzling, in early December. The spacious car park was almost empty. I ordered another Uber, but my mind was 4,200 miles away on a motor car in 1937. Its driver said that he was ferrying “five or six” passengers, when it was apparently attacked.

The building I’d been in is very much like most modern libraries you’ll encounter, ordered and well-run, with a friendly and helpful staff. Only its name – Midwest Genealogy Center — sets it apart: It’s a branch of the Mid-Continent Public Library system covering three Missouri counties, Clay, Platte and Jackson, the last being the most famous, as it encompasses Independence, Mo., and Kansas City.

The librarians there showed me some of the resources available, both on-site and online at home, for the counties’ residents who become members. They suggested that I look at the Irish Newspaper Archives.

So, I spent a couple of hours, when I could’ve easily spent a couple of days, browsing through some of its contents. I saw the Ballina Herald listed, which I’d never heard of, and looked up its coverage of the last time Mayo won the All Ireland football final, in 1951. I was surprised that right at the end of World War I at how much Ireland figured in a newspaper in Butte, Mont.

My first idle efforts at keying in actual people didn’t lead anywhere. I tried a great-great-grandparent’s name and then someone famous. Nothing. So, one of the librarians suggested quotations around a name, and I keyed in a narrow date range. By this point, I had something definite in mind.

And there it was on Sept. 29, 1937, in the Evening Herald, with two follow-up pieces on an appeal in January in the Herald, a broadsheet at that time, and its sister paper the Irish Independent.

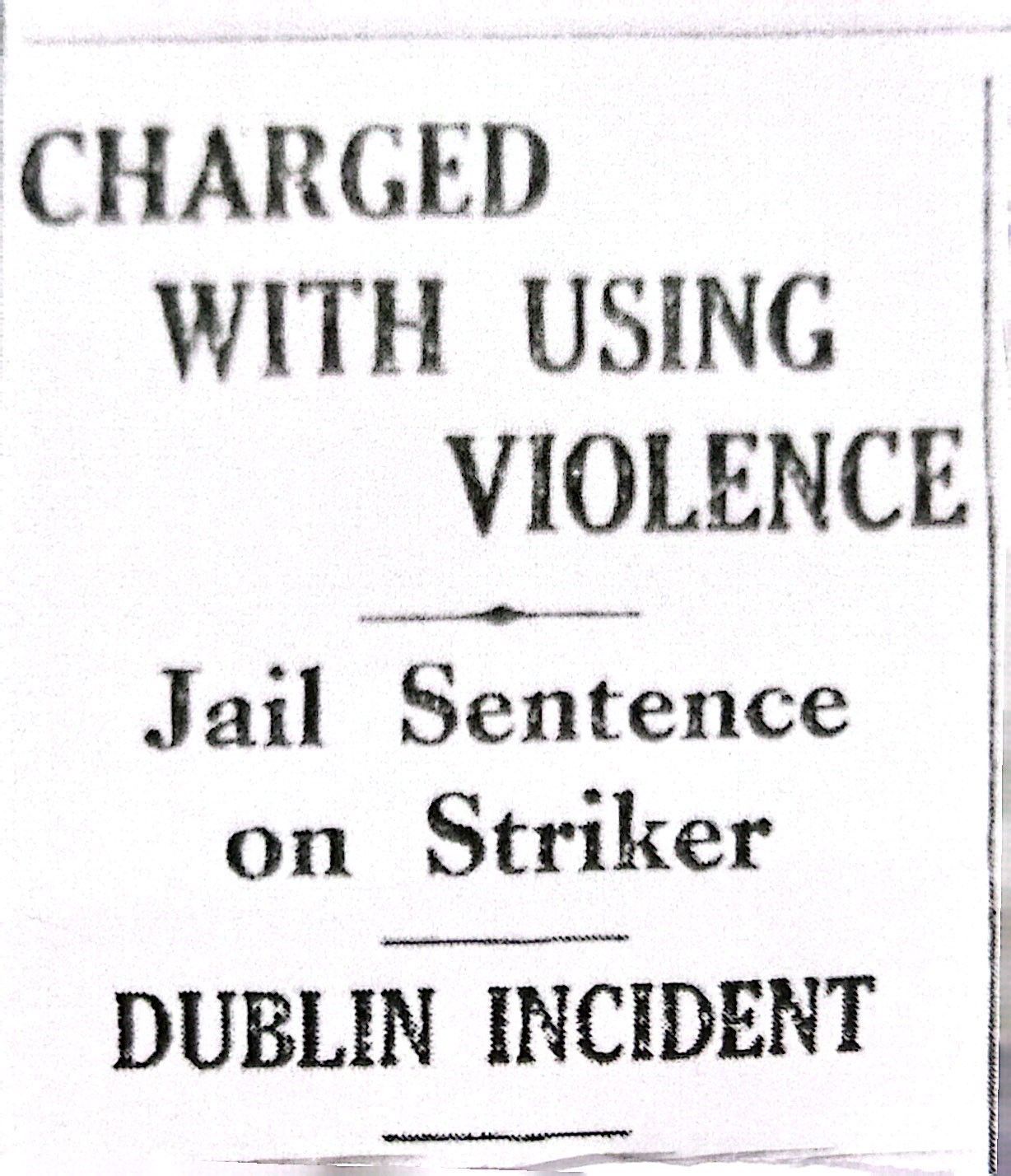

In the headline in all caps in the Herald: “Charged with Using Violence,” and subhead “Jail Sentence On Striker” and then, all caps again, “Dublin Incident.” The incident had taken place five days earlier, on Friday, Sept. 24.

Italy’s dictator Mussolini was in the news in the main story on the front page, having done a joint event with Hitler; while another adjoining report had an RAF detachment going to Gibraltar as part of a multinational effort against piracy.

There was no shortage of names in the court story I found -- quite the cast of characters, in fact.

A policeman, Guard Albert Long, the works manager Patrick Conboy, of Messrs McCairns’ Motor Works, Ltd., Alexandra Road, East Wall, in the port of Dublin; Mr. O’Sullivan, District Justice; Mr. J.A. Geary, Chief State Solicitor’s Office; Mr. P. Campbell, solicitor for the defense, two additional workers who weren’t on strike, the defendant, who was, and four other strikers.

The charges were throwing a stone, intimidation and malicious damage to property.

“Patrick Mulhern, of 13 Herbert Street, an upholsterer on strike” who’d been sentenced to a month in prison, lost the appeal in January. The shorter of the appeal pieces was buried inside – instead of sharing space with Il Duce, it was just above “Golf Club Dance.”

This was of particular interest to me as this 34-year-old convicted man, Patrick Mulhern, is my maternal grandfather.

One of his surviving children, my uncle Paul Mulhern, told me, “My mother, your grandmother, hated visiting him in Mountjoy. She said she would never forget the pervading smell: a combination of sewage, Dettol [antiseptic liquid] and cabbage. It was an awful place.”

He said she found it a “humiliating” experience.

By the time Paul was born in 1944, Grandad was serving as a Royal Air Force military policeman on bases in England and Northern Ireland. He believes he was working in England when he joined. “That was the great thing about it. When the war broke out,” he said. “They looked into nobody’s background. You’d just enlist. No questions asked.”

At the outset of the war, on a trip back home in Dublin, he’d also joined the Local Defence Force, specifically its 26th battalion, which was comprised of people who’d once been in the IRA, and particularly those who opposed the infant state during the Civil War. Grandad was picked up in late 1922 at age 19 and spent more than a year in the Curragh internment camp -- Tintown No. 3, specifically -- in County Kildare. That’s a family story for another day.

I heard none of this directly from him. The man called “Daddy” would from the 1960s onward also be referred to as “Grandad,” but he was never addressed as the latter in life.

He developed a heart condition in his early 50s, which was linked to his having childhood rheumatic fever. Giving up cigarettes was not high on the priority list in those days, it seems. Suffering a fatal heart attack on Oct. 10, 1958, he said to his 14-year-old son, “Give me over that packet of cigarettes.”

He lit his last Woodbine. “He thought it would relax him,” Paul said. His father was 55.

The evidence

So, what happened on that Friday afternoon, 21 years earlier?

A motor vehicle had been put at the disposal of workers not on strike at McCairns. It turned from Alexandra Road onto East Wall Road in the direction of Fairview, a suburb just beyond the north inner city, and when it drove past the picket of a reported six to nine strikers, the accused, according to Guard Long, threw the stone.

There were also charges of “threatening behavior and throwing missiles on the public thoroughfare on the same occasion.”

The works manager estimated that the damage to the car was about £5, which is close to £500 in 2023 spending power.

“To Mr. Campbell, witness [Conboy] said that Mulhern, who was a charge hand and was on strike, was a first-class worker and bore a good character.

“Mr. Campbell [asked Conboy]— if he gives you an undertaking not to repeat this conduct, would you personally be satisfied? – Personally, I would.”

“Mulhern, in evidence,” in the paper’s summary of my grandfather’s testimony, “said the men in the car coming out of the works were jeering and laughing at the picket. The car pulled up a short distance away and four men got out, one in a fighting attitude.

“He denied throwing a stone,” the report continued, “He would give an undertaking in respect of his conduct in future.

It then named four strikers on the picket line who testified that “they did not see Mulhern throw a stone.”

It continued, “The Justice said that if a chip of a glass got into the driver’s eye it would be a very serious thing, perhaps involving loss of life.

“In case there should be a desire to appeal, he fixed bail at two independent sureties of £10 each and personal bail of £20.

Did he do it?

What do family members make of these press accounts?

“I don’t know what to think,” was one response I got from two people.

It’s clearly a different experience hearing a story, a family legend from the distant past, and reading a newspaper report as if it had happened yesterday.

There was a note of caution from someone with professional experience in the area: don’t believe what you read in newspapers when it comes to courts coverage, as key elements can get left out.

Another added that Grandad, by reputation, “wasn’t backward when it came to throwing a punch,” but he also was known as to be “a very principled person” and thus it’s easy to believe that he took the fall for the group.

“My father was Bolshie,” Paul said. “He was very, very left-wing.”

“I wouldn’t put it past him,” he added about the main charge. “He could be volatile.”

If there’s a feeling that he was capable of it then, there’s also a willingness to accept his denial, which carries a certain weight over time.

And short fuse or not, a punch is not a stone. The throwing of a stone sounds more like the act of an impetuous youth. Would a 34-year-old with a wife and child at home, someone who was likely cast in or had assumed a leadership role on the picket line, get this carried away late on a Friday afternoon?

With feelings still raw four days after the incident, would the works manager on the opposite side of the picket line commend his character and the quality of his work, as he did under cross-examination, if he really thought him guilty of the assault?

Mountjoy Prison in 2006. [Rolling News.ie/Graham Hughes]

It seems, though, that with other charges in place -- intimidation and disorder on a public thoroughfare – it was possible to look past the sparseness of testimony (one guard vs. five strikers) linking the defendant to the stone and confirm the sentence. He was a ringleader and somebody had to pay.

The defendant at the appeal did not “deny the evidence of the Guards.” But then the summary of the prosecution’s evidence, according the press at least, was that “one of the strikers” threw a stone.

Interestingly, the family member that I could most count upon to take a detached analytical approach said that reading the reports it was clear there was a stitch-up – the fix was in.

“A stone is not the Russian Revolution,” he said.

It’s true that the courts system, law enforcement and the authorities generally favor those who stay in work over those who go on strike. The media, too. One report on the McCairns strike referred to the strike-breakers as the “workers who remained on duty,” as if they were soldiers who hadn’t run for the hills at the first burst of canon fire.

They were certainly not conflict adverse – as they showed with their provocative behavior towards the strikers and their failure to turn the other cheek when their car was attacked. One might reasonably speculate that my grandfather confronted the guy who exhibited the “fighting attitude” and that Guard Long then had his stone-thrower.

Yet, Judge Shannon of the Circuit Court was referring only to the strikers when he said he “could not allow such blaguardism as had been seen in this case” (let’s not forget that the strikers would have seen the strike-breaking itself as a form of blaguardism).

“Leniency had been shown from time to time,” he was paraphrased saying at the appeal, “but it had been ineffective, and he had no alternative except to affirm the District Justice’s order.”

“At the end of the day he went into the slammer,” my uncle said about his father. “That’s it.

“When he came out of Tintown in the Curragh, he had no criminal record,” said Paul, a grandfather to five. “Once he came out of the courts and Mountjoy he had a criminal record that would follow him for the rest of his life. It made him basically unemployable.”

(The police never figured in the family story, incidentally. Local guards looked out for my grandmother and her young family when my grandfather was working away from Dublin. “It was a perfect example of community policing,” my uncle said.)

Granny told Paul about the incident and the sentence when he was in his later teens. I also heard it in my later teens, from my mother. She was the first born and had been close to her father. Her version, though inaccurate by its omission of some key details, sounded closer in tone to his court testimony. And she got the length of the sentence right, whereas Granny said it was three months, which is maybe what it felt like remembering back.

I was a first-year in college at this time and had joined the Labour Party. Grandad had voted Labour and for left-wing candidates after the war, I was told. He was a fan of 1913 Lockout leader James Larkin, whose two sons had followed him into Labour electoral politics.

Paul said Granddad was a great admirer of and voted for Dr. Noel Browne, a mentor and friend later on to the current President of Ireland Michael D. Higgins, once a radical Labour firebrand. As minister for health in the 1948-51 government, Browne took on the Catholic Church and the medical profession with his plan for free state-funded healthcare for all mothers and children aged under 16, with no means test. He lost. Paul added that his father was secular and tolerant in his views and strongly objected to any expression of antisemitism.

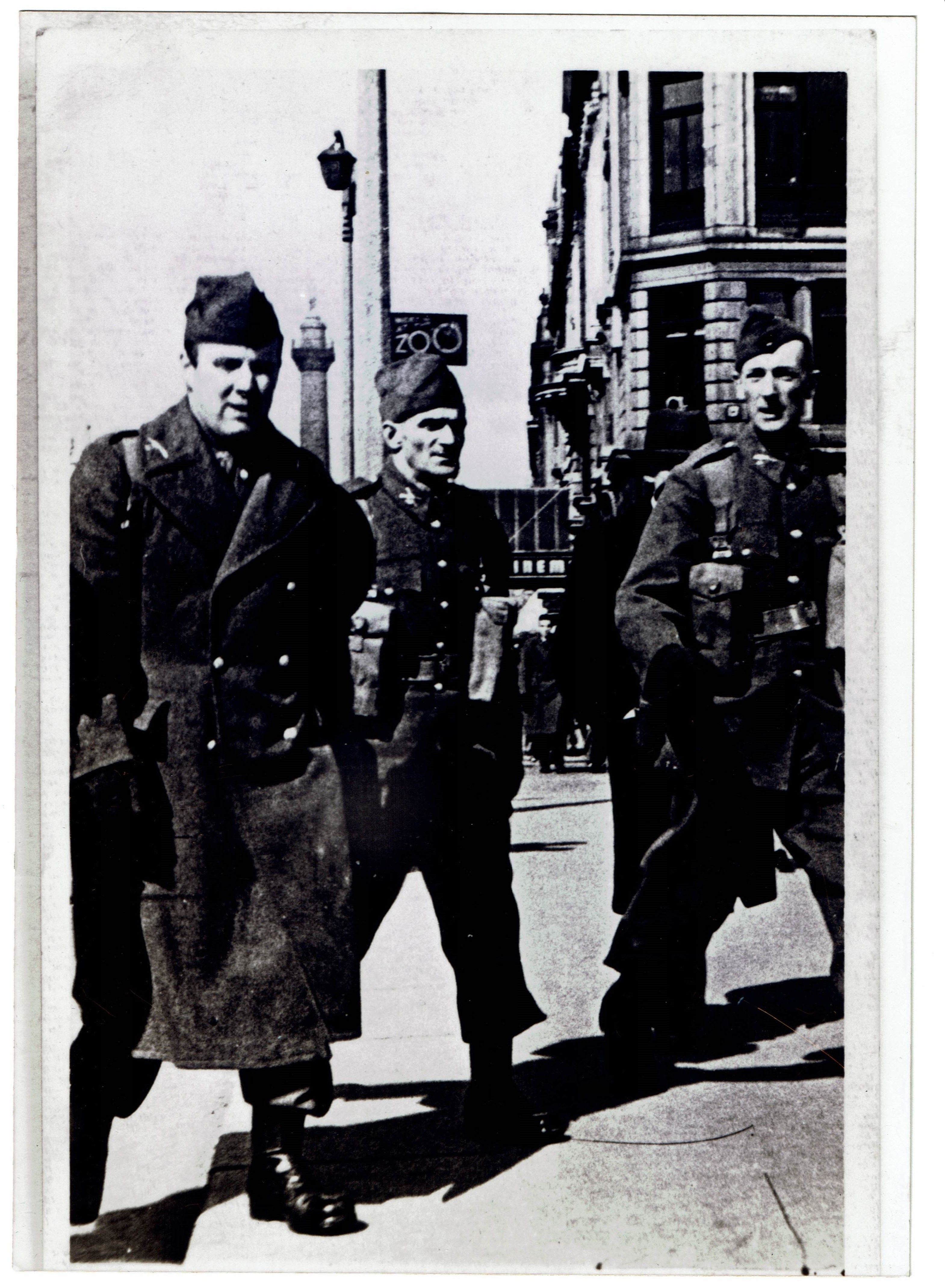

Walter Reuther, fifth from left, and other United Auto Workers leaders being approached by Ford Motor Company security guards ahead of the “Battle of the Overpass” in Dearborn, Mich., on May 26, 1937.

I have to say when I first found the reports thanks to the Midwest Genealogy Center, I reflected mostly on the year — 1937. What else was happening that was somehow connected? Well, the week my grandfather was charged, the American Legion said it would be up to individual members whether or not they wanted to back or oppose certain industrial actions. It would not do so as an organization.

I remembered that 1937 was the year there were intense battles between the Ford Motor Company and the UAW in Michigan.

This was the year, too, George Orwell published “The Road to Wigan Pier,” and the civil war in which he fought was raging in Spain. Mussolini’s most famous prisoner, Antonio Gramsci, had died on April 26, a few days after being unconditionally released.

Post-war

When he demobilized from the RAF in 1945 or ‘46, Grandad faced bleak prospects at home. Working in England might have been an obvious choice, but Granny’s parents and all of her siblings, to whom she was very close, lived in Dublin.

Grandad started his own upholstery repair business, located at a muse behind a house that was near the family’s flat on the South Circular Road, but the supply of business dried up in the 1950s as cars increasingly used plastic seating.

Paul recalled he got piecework at a factory on Spa Road, Inchicore. He walked there and back to save on the bus fare. “Granny used to wait for him in the window because if he was without his toolbox he had another week’s work,” he said. “If he came home with his toolbox, he’d been laid off.”

His last regular gig was working in Brittain Dublin Ltd., a car factory in Rathmines, the exterior of which is still there, Paul noted. He maintained his union membership, and his son has his cards for the last five active years of his life.

Paul has always voted left and left of center, but wasn’t a union member. He worked with the Hibernian insurance company, now known as Aviva, throughout his working life and wrote a book about its first 100 years.

However, his wife, Helen, a native of Tralee, Co. Kerry, served variously as secretary and treasurer of her constituency Labour Party on the north side of Dublin. In recent years she switched to the Social Democrats in solidarity with her TD Roisin Shortall.

(It was a source of confusion that someone with the same name as Paul, an ice-cream salesman with HB, ran for Labour in the west of the city. He never met this man, but it was the era when the telephone directory was king and he’d occasionally get calls like: “What happened to my ice cream?”)

One of Paul’s sisters, a nurse, was a Labour candidate for her local council in suburban London during the Blair years, while her husband, a union activist, ran for the party in the same election. They both won.

In the end, there was another side to Grandad’s working legacy – he passed on all of his expertise to Granny, who went on to have a successful business making curtains in the 1960s and ‘70s. Still a mother to young children when he died, she lived on in their South Circular Road flat until her death in 1990.