In times of crisis, unionism still reverts to the Lundy principle and the predictable rhetoric it entails. In the siege of Derry in 1688 the Catholic forces of the recently deposed James II surrounded the largely Protestant city.

Its governor, Robert Lundy, a Scotsman, wanted to negotiate a surrender because he was convinced that they didn’t have the resources to withstand the siege.

Thirteen apprentice boys bravely defied him and asserted their leadership of the dire situation. The siege lasted 105 days. Derry’s inhabitants were reduced to eating dogs “fattened on the flesh of the slain Irish," as well as horses and rats.

Fever swept through the city and multiple thousands died, but the defiant cry of no surrender empowered the protectors of the city until they were relieved by the army of the new king, William of Orange.

Every year in the month of July the Orange Order, led by proud modern Apprentice Boys, celebrates that valiant defense of Derry, and they still burn the effigy of a man they identify as a craven coward with a clear message inscribed on his chest “Lundy the Traitor!” The Apprentice Boys themselves stage two annual gatherings, one in august, the other in December.

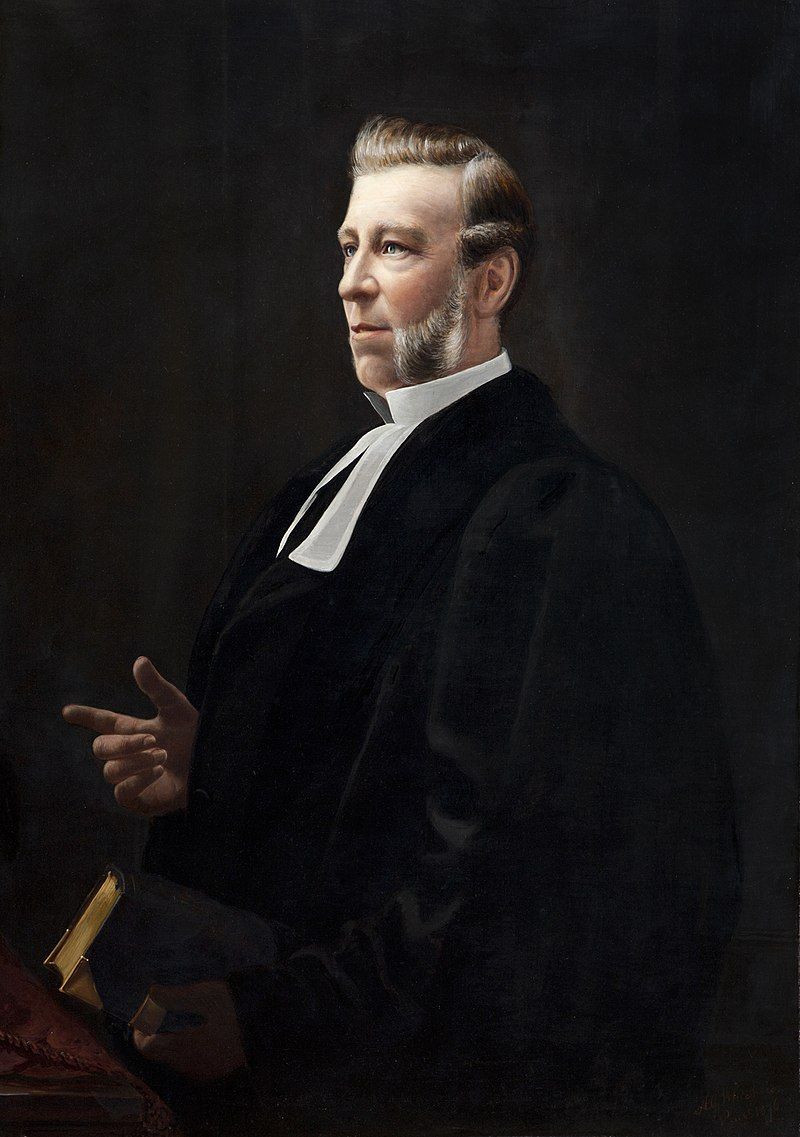

Roaring Hugh Hanna as depicted in a portrait by Augustus George Whichelo.

A few years ago, when the Democratic Unionist Party leader, Arlene Foster, was deemed to have veered from the hardline position of her party on abortion she feared what she called unionism’s traditional tendency of harsh treatment for Lundies, the equivalent of a primal scream warning against taking any step towards political moderation. Foster resigned the party leadership rather than face the ire of her constituents.

The current leader of the DUP, Jeffrey Donaldson, faces a similar dilemma because the party is engaged in heated internal discussions about accepting or rejecting the terms of the Protocol negotiated between the European Union and the British government and overwhelmingly endorsed by the legislators in Westminster and Brussels.

The principal DUP objection centers on their belief that the protocol weakens their central claim, their raison d’etre, contained in Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s famous assurance that they are as British as residents of Finchley.

That version of identity has changed dramatically over the years. A Loyalist lady eloquently explained their frustration at a recent July protest: “Bit by bit they have taken it all off the Protestant people. We have nothing left. They say we are still in the UK, but are we? Just about! And for how long? When your back is against the wall what do you do?”

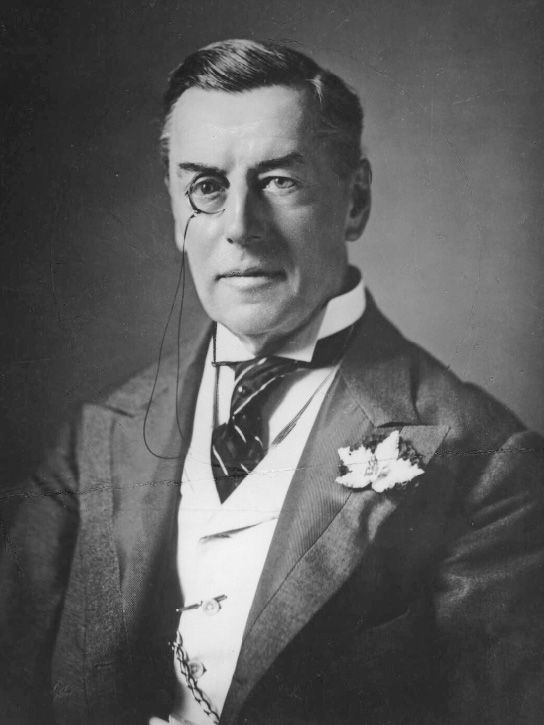

Joseph Chamberlain.

A recent LucidTalk poll in Northern Ireland gauging satisfaction with the 1998 Good Friday Agreement supports the depressing sentiments expressed by this beleaguered woman. While less than one-third of the total poll respondents said that they would oppose the agreement today, 54% of unionists claimed they would reject it.

60% of respondents said the DUP should go back into a power-sharing government in Stormont, but this number dipped to a measly 21% among unionists.

Roaring Hugh Hanna, the talented anti-Catholic 19th century Presbyterian minister, whose thundering sermons reputedly frightened the horses tied to the railings outside his church, summed up well the core value of loyalism then and now: “our future lies in the union with our kith and kin across the narrow seas.”

In the local elections in May, Sinn Féin upped its vote by an impressive 7% and made substantial gains in council seats. The DUP held its previous support and remains by far the largest unionist party. They are entitled to the post of Joint First Minister if they agree to rejoin the government at Stormont where Sinn Féin’s Michelle O’Neill would lead the nationalists, now holding a majority.

O’Neill attended Charles’ coronation and her rhetoric has become noticeably conciliatory. She rarely mentions the controversial border poll and Republican talk about the glories of the Fenian tradition have been superseded by repeated pleas to her own community leaders to reach out to unionists to ensure that their rights are valued and respected. Likewise, Sinn Féin invitations to the DUP to join them again in government at Stormont are low-key and never preachy or condemnatory.

This magnanimity is reminiscent of The Purchase of Land Act of 1891 which ended landlord control over their estates in Ireland. Prominent British statesman Joseph Chamberlain famously declared in Westminster that the popular bill was designed to mollify the Irish, in his words in parliament “to kill Home Rule with kindness.” Does the placatory promptings of the current Sinn Fein leadership amount to a kind of reverse replay of the Chamberlain dictum?

Kith and kin stuff is fine when the drums are beating in July and August, but what about real economic issues affecting the daily lives of the people in the North? The story here can only be spoken of in dire terms.

Northern Ireland is at the bottom of the UK league in the area of household discretionary income, and it has the lowest level of economic activity compared to England, Scotland or Wales.

According to a report by the prestigious Joseph Rowntree Foundation, about one in four children in Northern Ireland are living in poverty.

The JRF uses relative poverty as a measure of the standard of living in the community. An individual is judged to be in relative poverty if they are living in a household with an income of less than 60% of the average in other UK countries.

Using that metric, the report suggests that 300,000 people in Northern Ireland live in poverty – almost one-in-five. The poverty rate is highest among children with 24% living below the poverty line.

Approximately 4-in-10 children in Belfast are eligible for free school meals, a crucial benefit whose continuation along with badly-needed improvement in the deteriorating health service are in serious question without the restoration of an executive in Stormont.

These are shocking economic statistics but the even bigger elephant in the room continues to be the political instability that followed the Brexit fiasco. Local government in Stormont has been prorogued for years with serious detrimental effects for democracy in the province.

A U.S. investment conference in the North next month, followed in October by an American trade mission, suggest that American companies are attracted by the easy and uncomplicated access Belfast provides to the UK and EU markets.

However, the political instability conveyed by a failure to agree a working system of local government arguably dooms the prospects for any reputable company starting a subsidiary there.

The DUP bears sole responsibility for this untoward situation. They are facing an even bigger challenge than sorting out the protocol. How do they change their attitudes and policies and rhetoric at a time when nationalists outnumber unionists in the North?

Disparaging a Lundy man who died more than 300 years ago provides no pointer for a way forward.