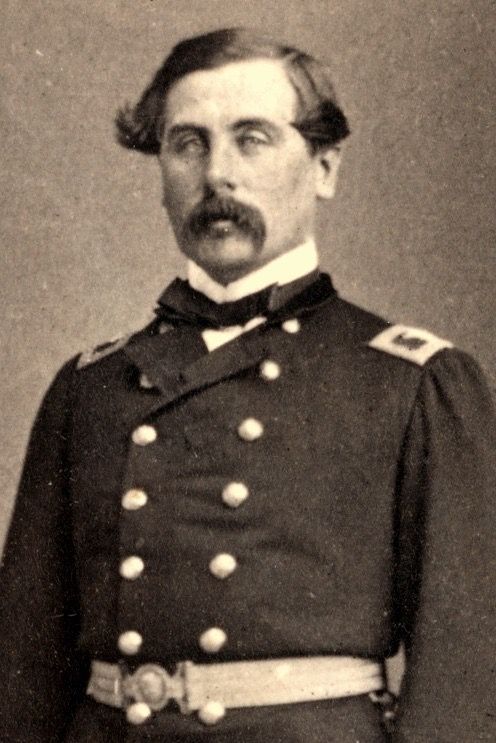

While recently in Ireland, I visited its oldest city: Waterford, whose mall is dominated by an imposing equestrian statue of Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher, a hero in two countries. Meagher is revered not just in his native Ireland, but also in the United States, where he valiantly led Irish troops fighting to preserve the Union in the Civil War.

Meagher rebelled against British rule in Ireland, but he was an unlikely rebel. Born into a prosperous merchant family in Waterford in 1823, the son of Waterford’s mayor, Thomas Francis came from a family that owned Waterford’s most elegant inn, the Granville Hotel, which still serves visitors just around the corner from his statue. Had young Thomas Francis not been a patriot, he could have enjoyed a life of privilege and might have followed his father into Parliament, but the blood of a rebel flowed in Thomas Francis’s veins.

Unlike many of his fellow Irishmen, Meagher’s family was wealthy enough to provide Thomas Francis with a first-class education at the renowned Jesuit Clowngowes Wood College, where he not only proved himself a fine student, but also a strong orator and powerful debater. At 16, Meager wrote a history of the school’s debating society which was presented to Daniel O’Connell during a visit. Reading the work, O’Connell made a prescient prediction: “A genius that could produce such a work is not destined to remain long in obscurity.” Meager fumed at the poverty and oppression Irish people suffered under British rule. He grew impatient with the moderation of many Irish politicians and appalled at the passivity of the Catholic Church in the face of such suffering. By the time he left Clongowes Wood, at the age of 16, he harbored a deep resentment of British rule.

Deciding to become a lawyer, he traveled to Dublin to study for the bar, but he became heavily involved in the Repeal Association, which worked to break the union between Great Britain and Ireland. Meagher became radicalized by his reading of Thomas Davis’ paper the Nation, famous for its nationalistic fervor. In 1847, the great hunger began to ravage Ireland, leading to the worst year of mass starvation and infuriating Meagher and the Young Irelanders, who railed against British indifference to the deaths of so many.

In 1848, a series of revolutions, beginning in France, swept Europe, giving hope to Meagher and the Young Irelanders that a peaceful revolution could free Ireland. The British government, fearful of an Irish revolt, passed a series of repressive, anti-sedition laws, which Meagher violated in a speech threatening revolt. Within days of the speech, Meagher was charged with sedition. Released on bail, Meagher and other Young Irelanders went to France to seek its support for an Irish uprising. Though their request for help was denied, they returned with a tricolor flag of green, white, and orange, which Meagher presented in a speech to the nation in Waterford and soon he urged his followers to prepare for war.

Alarmed by the situation in Ireland, the British government passed the Treason Felony Act, which punished "sedition" with death. Meagher and the other Young Irishmen revolted, but the rebellion was soon crushed. On August 12, of 1848 Meagher was arrested and charged with "High Treason." Found guilty of sedition and treasonous activity, Meagher was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. His statement before being sentenced has become legendary, “My Lord, this is our first offense, but not our last. If you will be easy with us this once, we promise on our word as gentlemen to try better next time.” Due to public outrage, his sentence was commuted to banishment for life, and Meagher was shipped to the Australian penal colony of Tasmania, where he lived for four years.

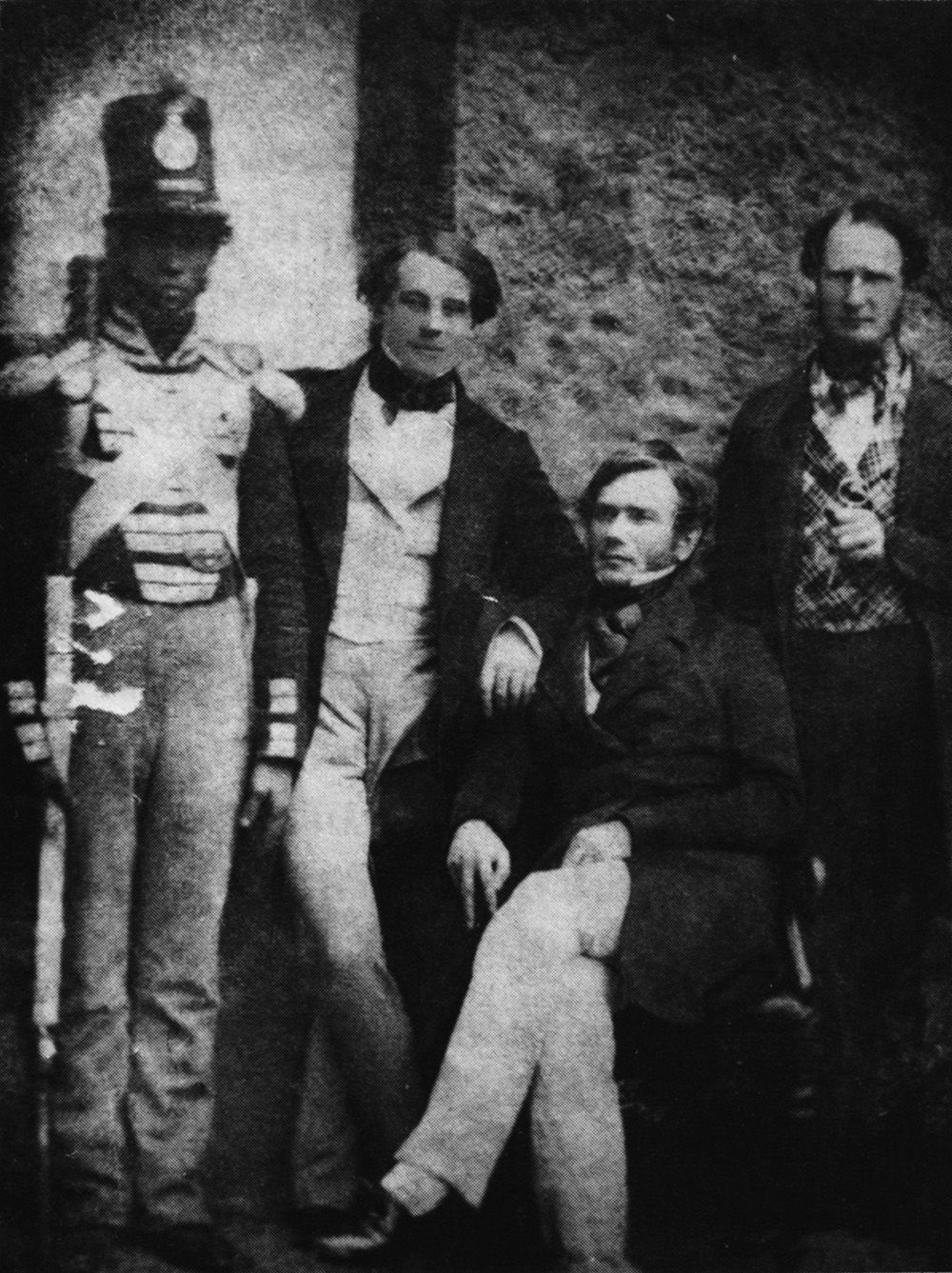

A soldier, left, Thomas Francis Meagher, William Smith O'Brien and a jailer at Kilmainham Gaol in 1848.

Aided by Irish rebels in New York, Meagher and other Irish rebels exiled in Australia managed a daring escape and arrived in New York City in 1852 to a hero’s welcome. Meagher studied American law and journalism and soon became editor of an Irish émigré paper, the Irish News. He became a U.S. citizen and was admitted to the New York bar in 1855. Meagher also became a popular speaker denouncing the British presence in Ireland.

In 1861, the Civil War broke out, but many New York Irish did not support the Union’s cause. Meagher, however, denounced the Confederacy and slavery and began recruiting men for the Union Army. One of his ads in the New York Daily Tribune read: "One hundred young Irishman—healthy, intelligent and active—wanted at once to form a Company under command of Thomas Francis Meagher.” He became an officer and his troops were placed in the New York 69th Regiment. When its captain was captured, Meager replaced him as its leader.

Meagher and his Irish troops distinguished themselves at the battle of Bull Run, where Meagher swung his sword over his head and shouted, “Come on, boys, here’s your chance at last.” The 69th charged uphill three times attacking the Confederates, but they were repulsed in very heavy fighting. One Confederate officer noted that “the Irish fought like heroes.”

Soon Meagher persuaded the government to allow him to reform the 69th as an exclusively Irish unit. Meagher succeeded in recruiting many young Irish men. The new recruits, however, were often not motivated simply by American patriotism. They considered service in the Union Army a good way to obtain military training for an eventual armed invasion of Ireland.

The troops he commanded, the “Sons of Erin,” carried distinctive green flags, embroidered in gold with a harp, shamrock and sunburst. Meagher’s Irish soldiers fought valiantly in some of the bloodiest fighting in the Civil War, charging into the fray with a half-English, half-Gaelic battle cry that rivaled the dreaded Rebel yell. They won honor at the battle of Antietam, the bloodiest day in American history, with Meagher leading them into battle; however, it was the horrible slaughter at the battle of Fredericksburg where the 69th achieved eternal glory. The 69th was ordered to make a suicidal charge up a steep hill that was defended by entrenched Confederates. Meagher’s Irishmen charged uphill into withering fire. Confederate General Robert E. Lee admiringly declared of the Irish brigade, “Never were men so brave.”

The 69th, however, had been shattered. Only 250 men of the 1,300 who had charged up the hill were present and accounted for. Almost 500 men had been killed or wounded; one company was down to three men. The 69th was further decimated at the battle of Chancellorsville. Angry about the destruction of his regiment, Meagher resigned his command on May 6, 1863. He intended to return to New York and devote all of his time to raising a fresh unit , but hearing of the decimation of their countrymen, few Irish volunteered. Meagher returned and commanded other units, but without the same elan he had shown in leading the 69th. Perhaps as a result of the horrors he had seen, he began to drink heavily and suffered from depression.

Finally, the war ended and Meagher left the military to embark on the last great adventure of his life as the new territorial governor of the Montana Territory. He was eager to help Irishmen emigrate to Montana, but he soon died in a tragic accident. Sometime in the early evening of July 1, 1867, Meagher fell overboard from the steamboat “G. A. Thompson” into the rushing waters of the Missouri River. His body was never recovered.

Today a huge equestrian statue of Meagher also graces the Montana state capitol in Helena. A 2016 book by then New York Times staff writer Timothy Egan, “The Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero,” became a best seller. His Waterford childhood home, Derrynane House, now a museum, displays artifacts from Meagher’s life including two of Meagher’s swords and the coat he wore the day he first displayed the tricolor. Each year, New York’s Saint Patrick’s Day Parade is led by his New York 69th Regiment, a lasting tribute to this hero in two countries.