The Berkeley Library in Trinity College Dublin was built in the late 1960s and in 1978 it was named after one of its famous graduates, George Berkeley. It is recognized as the university’s signature library.

Mr. Berkeley served as the Protestant Bishop of Cloyne, but he achieved fame because of his brilliant philosophical writing and lecturing. He was the leading idealist - not the common current understanding of this term - of his time, meaning he denied the existence of matter, arguing that reality is constituted solely by spirits and their ideas, extending upwards all the way to God.

Readers may well join me in finding such ideas obtuse, almost incomprehensible. However, Berkeley’s thinking and voluminous writings feature prominently in university philosophy classes all over the world. His ideas provide a springboard for professors to engage their students in the age-old question: what is real in the universe, and can rational disputation enhance the search for a satisfactory answer to this question?

George Berkeley has been in the news lately because in an unusual development Trinity College decided to remove the name of their world-renowned alumnus from the entrance to their main library. Why make this extraordinary move at this time?

In the 1780s Berkeley endorsed the slave system and bought slaves to work his small plantation when he lived in Rhode Island. This brilliant man, wearing his bishop’s robes, further claimed that slavery was entirely compatible with Christian teaching: “slaves would only become better slaves by being Christian” – a perplexing statement from any source but mind-boggling when coming from an acclaimed Doctor of Divinity, someone who preached on the Sermon on the Mount.

Fintan O'Toole. RollingNews.ie photo.

In the 18th century there were serious voices raised against the abominable slave system by the nascent abolitionist movement. This group asked the basic ethical question about how one could ever morally justify treating a human being as a non-person without any rights. Their coherent arguments about the evils of slavery did not move Berkeley who also asserted that Irish peasants should be subject to the same chattel treatment as black people.

The record of the Catholic Church merits equal condemnation for its ambivalent pronouncements on this seminal issue. The first clear papal condemnation of slavery came from Pope Leo X111 in the 1880s, well after it was outlawed by most European countries. The moral halo rarely fits comfortably with any human institution.

We all know that many attitudes, practices and values of yesteryear are deemed anathema in our time and certainly that applies in considerations of race. To start apologizing for the sins of other eras, knocking down statues and renaming buildings, leads inevitably to a cul-de-sac question about where it all ends.

Now, there is a strong argument against applying modern standards and insights to human deliberations hundreds of years ago. Some prominent academics, led by Diarmaid Ferriter, professor of history in the Irish capital’s other great academic institution and my alma mater, University College Dublin, demur from the Trinity decision. They question the appropriateness of evaluating people who lived in past centuries by modern standards.

We all know that many attitudes, practices and values of yesteryear are deemed anathema in our time and certainly that applies in considerations of race. To start apologizing for the sins of other eras, knocking down statues and renaming buildings, leads inevitably to a cul-de-sac question about where it all ends.

Maintaining some level of consistency in decisions of this kind must also be part of the assessment. Another library in Trinity College is named in honor of James Ussher, a scholarly bishop, who, in 1626 declared “the religion of the Papists is superstitious and idolatrous; their faith and doctrine are erroneous and heretical.”

Another important library in the college memorializes a distinguished historian, William Edward Hartpole, who wrote in the 19th century that “Catholicism, on the whole, is a lower type of religion than Protestantism.”

We shouldn’t be surprised at these anti-Catholic sentiments because Trinity College, from its beginning in 1592, catered solely for the elite Protestant families occupying all positions of importance in the country. It was a colonial institution affirming England’s domination of Ireland. Only in the last sixty years have the gates been opened wide to Catholics.

Shakespeare warns us in Julius Caesar that “the evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.” A related thorny question has come to the fore in conjunction with the Berkeley controversy: how do countries or institutions or families atone for horrible past misdeeds?

Laura Trevelyan. BBC screengrab photo.

Laura Trevelyan, a former BBC journalist now based in the United States, explained that her family accepted responsibility for their engagement in the slave trade in the Caribbean. They have paid reparations to Grenada acknowledging that the family’s wealth was greatly enhanced by the free labor provided by hundreds of locals during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Ms. Trevelyan was asked about her great-great-great grandfather, Charles Trevelyan, who supervised relief efforts in Ireland during the desperate famine years in the 1840s. His heartless policies contributed to over a million deaths from starvation, and his name lives on in merited infamy in the great ballad “The Fields of Athenry.”

She conceded that the family would consider reparations for his cruelty, but she felt that, unlike Grenada, where family profits benefited directly from the forced labor, in Ireland he was a government functionary subject to instructions from the leaders in London. A fair point!

Perhaps Ms. Trevelyan would instead encourage her family to help charities badly needing financial support to ease the plight of hungry children in Africa and elsewhere. One of these charities, HOPe, was set up in New York in 1997 as part of the 150th commemorations of the Great Hunger in Ireland and it continues its commitment to anti-poverty projects today.

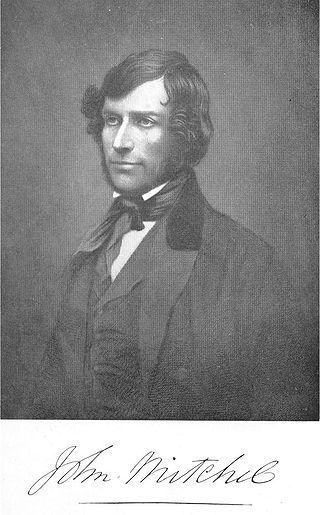

John Mitchel.

In writing about the Berkeley Library controversy, Fintan O’Toole, the brilliant Irish Times political essayist, focuses on the actions of the Irish revolutionary hero of the 1848 Rebellion, John Mitchel from Newry in County Down.

He was a leader of the Young Ireland movement which, in line with progressive revolts all over Europe, asserted Ireland’s right to freedom and an end to British colonial subjugation. Mitchel’s views were well-documented in his widely read book "A Jail Journal."

He and his family lived in the South during the American Civil War in the 1860s. He supported the Confederacy and lost two sons to that cause. His third son was badly injured, losing an arm in the fighting. Not only did Mitchel embrace the slaveholding cause, but he trumpeted it in his writing, objecting vehemently to the Confederate leadership proposal to enlist Black soldiers because that would diminish the purity of their racist cause.

When the Gaelic Athletic Association was founded in the 1880s around ten clubs used Mr. Mitchel’s name as part of their title. Not surprisingly, this includes Newry, where a statue is also erected in his honor.

The GAA has a fine record of anti-racism with many county teams including non-white players with full approval from its wider membership. Can they continue to look the other way while some clubs continue their association with a rabid racist?

Whether we are talking about George Berkeley or Charles Trevelyan or John Mitchel, symbols are crucial manifestations of the prevailing culture, and Trinity College has made a powerful and commendable statement about its values in our time. The GAA should do likewise.