Patrick Kavanagh has been referred to as the most important Irish poet in the decades between W.B. Yeats’s death and the rise of Seamus Heaney. And so, there’s always been an intrinsic interest in the man who penned iconic poems like “Advent” and “Stony Grey Soil,” which are among the best-known in Ireland. Additionally, Kavanagh was also one of the more colorful personalities in Dublin’s vibrant literary scene in the 1940s and ’50s. The fallings out and other alcohol-fueled antics alongside Flann O’Brien, Brendan Behan and some others were very entertaining when recalled affectionately years after the fact – such as in Anthony Cronin’s “Dead as Doornails” and “Remembering How We Stood” by John Ryan. Later on, in 2001, he was the perfect subject for the late Trinity professor and Kavanagh scholar Antoinette Quinn, who wrote what’s considered the definitive biography of him.

In Massachusetts resident Elizabeth O’Toole’s “A Poet in the House: Patrick Kavanagh at Priory Grove,” his distinctive voice provides wonderful material, too, but the portrait is a little different from the standard view.

One evening in early 1961, Elizabeth’s husband Jimmy O’Toole saw Kavanagh draped over the bonnet of his old Riley car at the corner of Stephen’s Green and Baggot Street in the center of Dublin. “Paddy had realized that he was too sick to be able to make it home to his own flat; recognizing the car,” she writes, “he had decided his best option was to wait there, because he knew Jim would take care of him.”

The doctor that visited the O’Toole residence at 47 Priory Grove, Stillorgan, felt the poet should be in the hospital, but he refused such a move and instead stayed for a period of several months with the couple and their children -- Larry, Margot, EllyMay and Jaja, who then were ages 10 down to 2.

Elizabeth already knew Jimmy’s friend Paddy Kavanagh, who was often “followed around by an entourage of admirers and ‘hangers-on’” and who sometimes “arrived at our house in the company of such people.”

There were many who were less admiring, like critics in the press who supposed, for instance, that his wearing old clothes to a society wedding [that of actress Kathleen Ryan, sister of the above-mentioned John] meant he felt he didn’t have to conform. Kavanagh replied that they were the best clothes he had.

“Much of what has been written about Paddy describes him as a difficult person,” Elizabeth O’Toole says. “These descriptions always make me wonder about how many personal insults Paddy bore on his way to obtaining his reputation for irascibility.”

In a 55-page afterword, the book’s editor Brian Lynch writes of Elizabeth’s account written in her 90s: “Some of what she heard over the years, she thought unjust and, although the memoir is not polemical or contentious, it is underpinned by the desire to correct the injustice. To her, Kavanagh’s character was complex and wilful, but also meeker, more vulnerable, less acerbic, warmer than the generally accepted evidence makes him out to be. As a poet, he had a profound influence on Elizabeth and her family, which she wishes to pass on to her children’s children. She also wants them to understand and appreciate what an extraordinary man her husband was.”

Earlier, in the book’s foreword, Lynch says, “Distance from her native country is just one of many reasons why she is not mentioned in any of the Patrick Kavanagh biographies … and it explains, too, why very few people, perhaps only historians of the Irish theatre, will remember that her husband, James Davitt Bermingham O’Toole, had once been a controversial playwright in Dublin.”

Jimmy O’Toole’s remarkable life began in China. His Clare-born father John, although from a family of agrarian radicals, joined the Shanghai police force after a few years with the Royal Irish Constabulary. When the nationalist Chiang Kai-shek’s forces began tightening its repressive grip the family left and Jimmy’s promising academic career continued in Ireland with an engineering degree at University College Dublin, following by an advanced degree there later on. His first job was at a factory in Nazi Germany, but after a time he had to go into hiding there.

At home, Jimmy O’Toole worked at a variety of companies in Ireland and then, in the immediate post-war years, in a series of engineering positions in Sheffield, Leeds and Rotherham in England. After his engagement to Elizabeth in 1948, he returned home to work with the Electricity Supply Board.

For reasons unknown, he fell out of favor with his superiors in that state body and his response was the play “Man Alive!” The Abbey’s managing director Ernest Blythe expressed interest, but decided against producing it; then the Gate went to the dress rehearsal stage before canceling it. It was finally given two week-long runs by the Olympia, and was published in 1962 as “Man Alive! A Play by James DB O’Toole” by Allen Figgis in Dublin.

In her own 22-page chapter, Jimmy and Elizabeth’s eldest daughter Margot O’Toole says, “My father’s exuberance enveloped those around him and swept them along. Patrick Kavanagh, often portrayed in years since then as a curmudgeon, joined right in.”

This included trips to the races and the seaside. (Jimmy O’Toole, a competitive water polo player, regularly brought his family to Seapoint on Sundays after breakfast and Mass.)

Kavanagh said to Elizabeth before reading her poetry in the middle of a working day at home: “Have you ever listened to a stream? Well, of course you have. The water is the water, and what you hear as it comes down the hill is the sound it makes when it bounces off the stones in the stream. I want you to be like the stones – silent. Let the words go where they may.”

Elizabeth O’Toole writes, “Patrick Kavanagh was consumed with a sense of the presence of God. It was not just that he believed in God, as I did. It was that he was aware of God’s presence in all things. This did not make him a ‘Holy Mary,’ or give him a ‘holier than thou’ attitude. On the contrary, as far I could see he allowed himself to be as free as the breeze to say whatever he liked and do as he wished.”

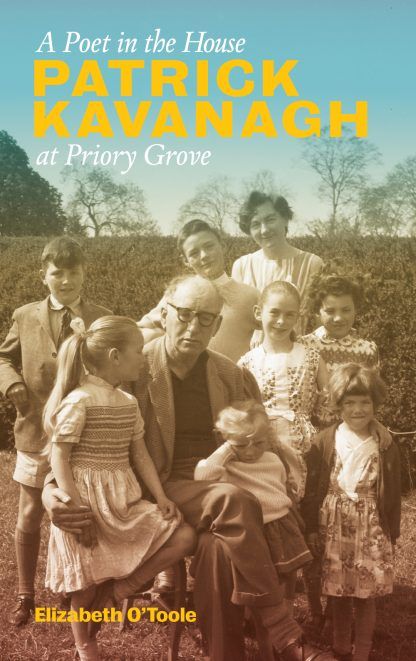

Lynch, who in his very early adult years knew the poet, says that in O’Toole family photos, Kavanagh “is unsmiling, dour, even fierce, wearing the public face he invariably composed for the camera, which is belied by the fact that the O’Toole children patently regard him not as ferocious but as a friend and companion.”

Says Margot O’Toole, “Paddy enjoyed the company of children. He showed an interest in us, he took part in our fun, and he was supportive. We shared with him what his poems asked children to share with him – the ‘meadow ways’ of our innocence and laughter.”

She adds later, “There seems to have been a healing and restorative dimension for him in the company of children. Little wonder that his poem ‘Advent’ he openly coveted ‘the luxury’ / Of a child’s soul’ as essential to his poetic vision.”

Lynch says, “In poetry, it was the child-like vision he had seen in Inniskeen in 1910 that he sought to return to, when his ‘father played the melodion’ and the poet was ‘six Christmases of age.’”

Margot O’Toole says, “Poetry was at the core of my parents’ friendship with Paddy. In our home, poems were part of daily life.

“Each of us learned a different set of poems. It was only after I became an adult that I realized each list must have been selected based on our individual personalities. For the most part, all of us knew the poems from all the lists because we heard them repeatedly recited.”

By 1963, Jim O’Toole was effectively sidelined by the ESB, by being given tasks that had little to do with engineering, and so he applied for and got a temporary position at Ohio State University teaching science writing to science, medicine and dentistry students.

“He was a perfect fit,” his daughter Margot writes.

He thrived in the academic life and eventually obtained a permanent position in Boston University and the entire family completed its move to the United States in 1967, the year Kavanagh died. After Jimmy’s sudden death six years later, Elizabeth continued her work for another two decades as a educator in the public school system in Massachusetts, having begun her career as an lecturer in colleges in Ireland.

She was one of seven children of Laurence Ryan, a County Clare farmer and thoroughbred horse trainer, and Helen Mary (May) Watson, of County Cork, who is described as a “businesswoman, pianist, trained in culinary arts.”

“I grew up on the Shannon estuary where the river turns to meet the sea and the Atlantic Ocean sweeps in and out of its own volition - where storms were wild and fierce and summer days seemed never ending,” Elizabeth writes. “I remember marshes crisscrossed with creeks, dragon flies hovering over pools of mushroom pink near the lapping waters of the river. In summer the meadows were sweet with scents of wildflowers. We were a horsey family, always ready to saddle up and ride. I remember how the foals nuzzled my mother. They knew her well for she was always there murmuring soft comfort when foals were being born. In summer I loved to run through our farmland and watch the sun go down in quilts of pink. And in the morning, it would rise and burst through the door of our dairy, brightening the milk buckets, and bringing a new day of promise.”

Lynch, who is a member of Aosdána, the Irish academy of artists, to which he was originally nominated by Samuel Beckett in 1983, says of Elizabeth O’Toole, “Not only was she kind in the sense of sympathy, she was independent, high-minded, not to be trifled with, capable, spiritual, a lover of literature and a friend to the poet.”

Elizabeth O’Toole

Date of birth: Sept. 7, 1924

Place of birth: Cratloe, Co. Clare

Spouse: James O'Toole (died Feb. 22, 1973)

Children: Laurence, Margot, EllyMay, Jacqueline

Residence: Newton, Mass.

Published works: “A Poet in the House: Patrick Kavanagh at Priory Grove.”

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

When I retired, I took up painting (and had an exhibit at Gallery), I appeared on stage in "Shadow of a Gunman,” and I also began writing (by hand) about my memories. My daughter, Margot, collected these handwritten notes. She compiled those sections pertaining to our time with Patrick Kavanagh. Eventually she had the bright idea of contacting the Patrick Kavanagh Resource Center, and through the connections forged there, the book was published, with Brian Lynch as editor, in December 2021. The first few printings sold out in days and the reviews lifted the spirits of this very old woman.

What book are you currently reading?

Nearly all of my reading these days is of poetry.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

I wish I had finished the book I was writing about my husband.

What is your favorite spot in Ireland?

Cratloe, Co. Clare.