On February 22, Trinity College Dublin made an historic announcement that it would return 13 skulls stored for over 130 years in the Old Anatomy Museum at Trinity College Dublin. They were stolen at the height of colonialism in 1890 from St. Colman’s cemetery on Inishbofin island, County Galway.

Provost Linda Doyle also issued a formal apology: “I am sorry for the upset that was caused by our retaining of these remains, and I thank the Inishbofin community for their advocacy and engagement with us on this issue.”

These human remains were taken from a recess inside the graveyard’s 14th century abbey built on the site of St. Colman’s original 6th century monastery.

A precedent-setting case in Ireland, the decision can serve as an example for other communities of origin globally who are seeking the repatriation of their remains.

At the American Anthropological Association conference I attended in the fall of 2022, I met with a Japanese colleague eager to see how the Inishbofin case progressed. He conveyed to me that it might help in efforts to return remains held in universities and other institutions in Japan that were taken from Indigenous Ainu communities he was working with.

I am a descendent of Inishbofin so these skulls could very well be my ancestors. My biological grandmother emigrated from the island to the U.S. Since my first visit in 1995, upon learning of my heritage as an adoptee growing up in New Jersey, I reconnected with cousins there and visit the island often.

The perpetrators who stole the skulls later became prominent in their scientific disciplines, including my own field of anthropology. Known as one of the founders of modern British anthropology, Cambridge University’s Alfred Cort Haddon was a zoologist based in Dublin at the Royal College of Science at the time.

If you check out Haddon’s Wikipedia page, you’ll see him pictured proudly sitting with a skull in hand! He brazenly documented the theft of the crania in his diary. His young accomplice, Andrew Francis Dixon, was a student of anatomy at Trinity who later became Professor of Anatomy at the College in 1903 and subsequently chair of the department.

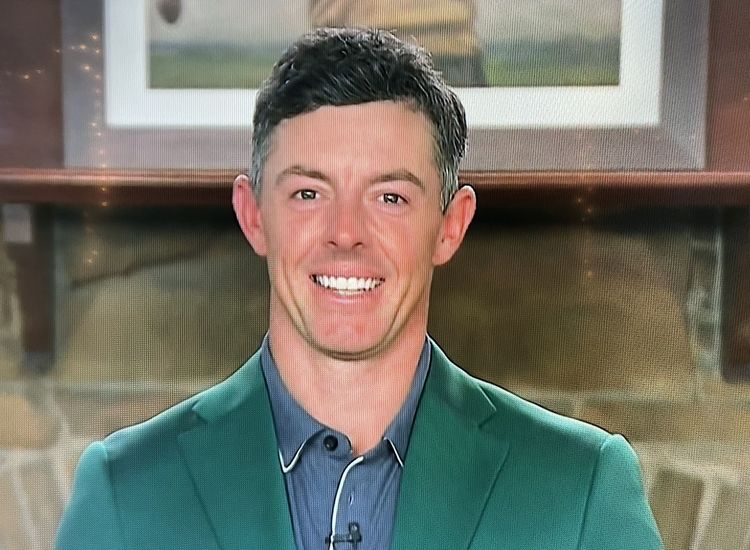

Marie Coyne, director of the Inishbofin Heritage Museum.

I became involved in the campaign to return the skulls in mid-2020, initiated years before by Marie Coyne, director of the Inishbofin Heritage Museum, and Irish anthropologist Ciarán Walsh, whose doctoral and post-doctoral work focused on Alfred Cort Haddon.

Marie has archived and collected an incredible number of documents, photos, and lifestyle objects - from century-old spinning wheels and boat anchors to dishware and lanterns. Her work keeps the history of the island alive, along with, among others, fellow Islander Tommy Burke’s socio-cultural history tours. Marie is in the process of raising funds to build a larger facility to accommodate everything.

Marie was one of the researchers on the 1993 publication, "Inishbofin Through Time and Tide," edited by fellow islander Kieran Concannon I came across on my first visit to Inishbofin.

The book is an invaluable resource. It’s what I would call a “self-ethnography." Oral histories and stories by islanders were featured, as were historical aspects of the island.

The book repurposed information from Charles R. Browne’s publication the previous century, "The Ethnography of Inishbofin and Inishshark" (1893). Browne’s study included photographs from around the island, cultural information, and charts with islanders’ cranial measurements, including my own great-great grandfather James Joyce.

Alfred Cort Haddon worked with Browne to set up the Anthropometry Laboratory at Trinity College Dublin in 1891 with a grant from the Royal Irish Academy. They measured heads, dead or alive. During this era, the practice of anthropometry, craniology, craniometry and even the pseudo-science of phrenology was used to assign ethnic classifications and to determine "intelligence" or placement on a racist evolutionary scale.

Another of Browne’s photos from Inishbofin pictures a man identified as Myles Joyce having his head measured by Browne as policemen of the Royal Irish Constabulary hover over him, likely to assure he complies. A crowd of villagers look on.

In December, 2020 Marie Coyne, Ciarán Walsh, and I wrote to the former TCD provost, Paddy Prendergast, requesting the repatriation of the crania. We received a positive response. This was followed up in February 2021 by a detailed, formal letter with additional signatures and a larger request for the return of the Inishbofin skulls and the entire Haddon-Dixon collection of remains taken from communities around the west of Ireland.

We argued these remains were likely acquired unethically, as well. Since their means of possession were not documented by Haddon as a theft as he had done in his diary regarding the Inishbofin remains, these became a harder sell in the short term.

That summer of 2021, my cousin Aoife and I were able to visit the skulls, long held hostage. It was a jarring experience to see them all laid out in a row on a lab table. I thought of all they had seen over this time as they sat on shelves or in storage at the Old Anatomy Museum.

They had been taken during colonialism, witnessed their country’s independence and later economic freedom as the “Celtic Tiger." They had seen the rise of women’s rights, and now a growing movement to support immigrants and refugees. All the while, the skulls remained locked away while those charged with their care appeared to indicate to us that day that they weren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Indeed, there were more hoops to jump through. A letter from the Anatomy Museum steering group to Ciarán Walsh sent in late August 2022 stated that “If the crania had remained in situ they would likely have disintegrated by now. Deterioration has been much reduced by secure housing and protective wrapping…”seemingly argued that they had been better at protecting the remains than islanders themselves.

The letter also stated it was “…not in a position to support a request for deaccession of the crania and transfer to the possession of private individuals or historical interest groups."

These are arguments heard time and again from museums around the world wishing to hold onto human remains or cultural artifacts in their collections. New York University, where I work, only recently returned the remains of 64 individuals, mainly to the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians from NYU’s College of Dentistry. They were acquired in 1956 by former NYU professor Theodore Kazimiroff from the National Museum of the American Indian’s Department of Physical Anthropology.

The August letter came immediately prior to our September 1, 2022 meeting with Provost Doyle’s office, which was nevertheless hopeful. Community representatives from Inishbofin zoomed in.

A meeting followed two months later at the Community Centre on Inishbofin with Trinity’s Colonial Legacies Review Working Group.

Since the Inishbofin skulls were the first case TCLRW was considering, they were simultaneously setting up the structure for future cases, such as questions concerning the potential renaming of TCD’s Berkeley Library, due to Berkeley's history as a slave owner.

Once the TCLRW process was underway, it was a matter of months from the September 1 meeting to the February 2023 decision, but nothing was certain until the end.

To get there, the Islanders and the public were invited to submit "evidence-based" material by early December.

Letters of support for the return of the remains were sent by, among others, the American Anthropological Association (AAA), the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA), the Society for Cultural Anthropology (SCA), and Notre Dame University.

We mounted two petitions demanding the return of the skulls, with no further evidence needed (since they were stolen to begin with). The petition on the island was signed by almost every resident, while the public petition on change.org garnered close to a thousand supporters, including many Inishbofin descendants.

We thought the end was in sight when Trinity’s board met on 14 December 2022. It was not the Christmas present hoped for as no decision had been made yet, but it was a step forward.

The next step took place at long last with last month’s final decision to return the stolen skulls to Inishbofin. The healing process can now begin as Inishbofin plans for their ancestors to come home.

Pegi Vail is an anthropologist (PhD 2004, NYU), filmmaker and curator at New York University’s Center for Media, Culture & History, teaches documentary filmmaking in NYU’s Culture & Media Program as well as anthropology courses at NYU NYC and NYU Prague. Her award-winning documentary "Gringo Trails" explored the long-term effects of global tourism. As a curator, she has collaborated with colleagues at American Museum of Natural History, National Geographic, National Museum of the American Indian, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and through organizations such as The Moth, the storytelling collective she was a founding member of and curator for. Her website is at pegivail.com