Duke University, 1984.

The night was a milestone in the life and career of actor Jared Harris, star of “The Crown, “Mad Men,” “Chernobyl,” “The Terror” and other streaming hits of the 21st century.

Richard Harris, who is perhaps best remembered for “Camelot,” “The Field,” “Gladiator” and the first two “Harry Potter” movies, sat quietly in the audience.

The young Jared’s divorced parents had decided years before he should be a lawyer. Elizabeth Harris, though, did like him in his plays, and once said to her ex-husband, “You should go down and see him, he’s very good.”

“Well, you would say that, you’re his mother,” was Richard Harris’s dismissive reply.

What he saw in “Entertaining Mr. Sloane” that night at Duke, however, swept away his skepticism.

“It changed our relationship,” the younger Harris said recently by phone from Los Angeles. “It was exciting.”

The multiple award-winning actor could speak now with his adult son about their shared enthusiasm or, in the father’s case, “obsession,” particularly when the discussion veered toward a topic such as his favorite play by Shakespeare.

Jared Harris will be in New York for the March 2 Craic Fest screening of “The Ghost of Richard Harris,” an entertaining and engagingly unfiltered portrait of the film star and hit-making singer, who was born in the city of Limerick in 1930 and died in London in 2002.

The roots of the documentary go back to an approach to the three sons of its subject in the late 1990s by its director and producer Adrian Sibley, who had done some films about actors for the BBC.

Harris, doubtful at first, was shown one made about Anthony Hopkins.

“He really liked it, and he and Adrian had dinner and got along very well,” Jared Harris recalled, “Dad said, ‘I’ll do this, but only if you accept that I’m going to lie to you half the time and I’m not going to tell you which half and I’m not interested in you trying to find out which half.’”

Sibley saw potential in the unreliable narrator concept, but the BBC did not. After his father’s death, Jared Harris and the filmmaker had conversations from time to time during which they’d express regret that the film didn’t get made. But when nothing substantial emerged in terms of a biography or a documentary they together revived the idea of doing it.

Harris liked that “Adrian’s approach wasn’t going to be a pedantic journey through the chronology of a life, about his career. It’s more about him, who he was. It tries to get a grip on the nature of the man.

“The tricky thing is how do you replace Dad because he’s not present to speak for himself?” he said.

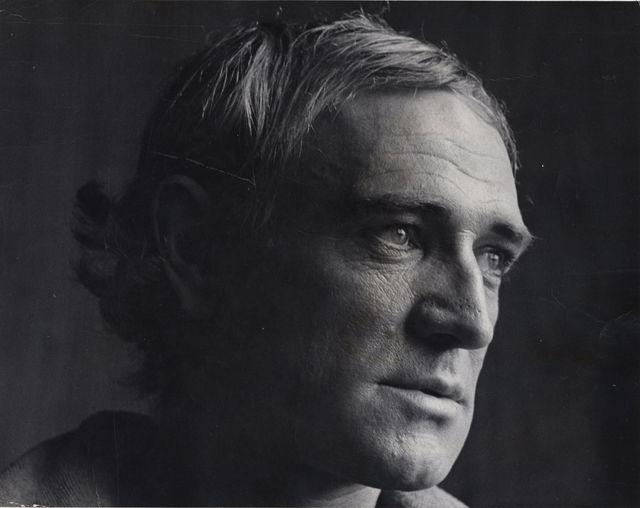

Richard Harris.

In time, they found a solution of sorts in an agreement made with journalist Joe Jackson to use some of the audio tapes of interviews he’d done with the actor over a period of 14 years.

The tapes uncover Harris’s bleak view of a humanity that has shown itself incapable of change over thousands of years, but also his belief that the individual should aim to live every moment to the fullest.

By this point, there were four Harris documentaries in the works. Sibley’s inevitably became the main one as his intention from the outset was to build it around Damian, Jared and Jamie Harris.

“The spine of the documentary would be the three of us trying to figure out who he was,” Jared Harris said.

They’re helped by interviews with people who could speak to Richard Harris’s growing up in an upper middle-class family in Limerick and his school days at Crescent College, and those who have stories about his vacationing in Kilkee, Co. Clare, which he did for three months annually from birth until he was 22.

Lelia Doolan recounts his transition from enthusiastic summer amateur in Clare to drama student and professional in London; agent Sandy Lieberson recalls his easy transition to Hollywood; Vanessa Redgrave explains the reasons why she fell in love with Harris the actor; Dick Cavett remembers “he delivered,” which is a television host’s equivalent to the print reporter saying he was “good copy”; Jim Sheridan reveals both his debt of gratitude to Harris and the scars inflicted by the “war” that was the set of “The Field”; while Russell Crowe pays homage to his co-star in “Gladiator.”

One starting point for the film and the sons’ quest is Elizabeth Harris’s line from her autobiography “Love, Honor and Dismay” that “Dickie Harris never left Limerick, and Richard Harris never went back.”

There are some surprises on camera as they sift through diary entries, poems and newspaper clippings.

Along the way, each brother offers perspectives that the other two presumably agree with or are sympathetic to. In Jared Harris’s case, one might include in that category his childhood memory of being “irritated” by his father’s status: “I wanted him to be my dad and not this person other people thought they knew”; and his admiration in adulthood for the bravery of his performance on the London stage in Luigi Pirandello’s “Henry IV,” which required that he appear to underperform in the first act and in the second have the audience wondering if he’d not perhaps slipped out of character. (Harris is just about at his happiest on screen in the documentary after being named Best Actor for the play at the Evening Standard Theatre Awards in 1990.)

The sons discuss whether and to what extent a well-publicized vacation their father took immediately after his divorce in 1969 was disrespectful to their mother. (Elizabeth Harris, who died in 2022, makes brief appearances in the film.) Harris was given a week’s break and an executive jet by the producers of “Cromwell,” a film about the most famous Puritan of them all, and the result was a European tour attracting headlines that served to underscore his “wild,” “hellraising” image.

Songwriter Jimmy Webb, who at age 21 wrote Harris’s hit song “MacArthur Park,” said, “I remember thinking, ‘I never met anyone who loved his children more.’”

“He was very attentive, very loving,” Jared Harris confirmed when interviewed.

“My friendship with my three boys is my life,” he told Joe Jackson, “They’re my life.”

Eva Juel Hammerich, his personal assistant for the last five years, said he “truly loved his sons and regretted that he couldn’t be the great father” when they were children.

If the Harris boys only saw each of their parents a few weeks at a time, it wasn’t because either or both had gone anywhere necessarily, as Jamie clarifies in the film, but because the children had – they were at boarding schools, from age 6 through to 18.

One of those schools was run by the Benedictines; part of the marriage deal was they would be raised Catholic, according to their father’s wishes.

“He had a Jesuit education and was extremely respectful of it, but at the same time acknowledged he didn’t take advantage of it,” said Jared Harris. “He resisted as hard as he could being taught anything, except for rugby.”

The once “semi-dyslectic” Harris, to use his own description of a youthful condition, enjoyed it when his sons returned from college with new ideas and information, and enthusiasm for literature.

“He definitely understood the value of education,” Jared Harris said. “He was an avid consumer of literature. Quite often when we’d go on holiday, he’d have one suitcase that was full of books. And he would disappear up to his room for three days and just read.”

It was almost a reenactment from his youth. He was a member of a large family, but his businessman father owned a large home, Overdale, and there was a bedroom for each child. Dickie was confined to his for a long time after he caught tuberculosis.

It was in his sick bed that he decided to be an actor; it was there, Malachy McCourt says in “The Ghost of Richard Harris,” he discovered his love of words.

In addition to being loving and attentive, with the kind of charm that made the person he was focused on feel the most important in the room, he was an “incredibly generous person.”

But he’d also disappear.

“He’d pursue his life,” Jared Harris said. “He found obligation extremely distracting. When he felt somebody had a hold on him, he would normally react in the opposite direction. He didn’t like going to people’s houses because he had to abide by their rules.”

“I enjoyed him being him,” he said of his extroverted father. “He was very entertaining.”

But the middle son himself was a “very shy person,” one reason his parents didn’t feel he’d be naturally suited to acting.

First-born Damian had declared early he wanted to be a director, and he became one. Jamie had a good singing voice and had an interest in music, while his “temperamentally gregarious personality” eventually led him down a career path in acting, with the family’s encouragement.

The lawyer idea for Jared came from his being “argumentative” as a child. There was a family precedent in that his Welsh grandfather, Elizabeth’s father, was a solicitor who went on to a public career, first as a Labour member of Parliament and later as a leading figure in the centrist Liberal Party.

“I didn’t like the life that was being mapped out before me,” Jared Harris said. “I went off to college in the United States, trying to find my own identity.”

After graduating from Duke, he returned to London to study acting. In conversations with his father from that time forward, he was told of the great productions and the great performances, from Laurence Olivier, Peter O’Toole, Paul Scofield and others.

“I was interested in something he was passionate about,” the son said. “I remember him vividly describing theatre performances that he’d seen; he’d describe them in great detail, with incredible insight and analysis. He’d act out certain parts of them.

“The moment in ‘Titus Andronicus’ when Olivier had his hand chopped off, he’d act that out. I could see why it landed in his memory the way that it did.”

Discussions would often lead back to “Hamlet” and the great actors who had performed in it.

“He’d talk about what that person got right, what he’d missed,” Jared Harris said, “What he’d never seen before.”

The best, the closest to perfection in the role of Hamlet, in his father’s view, was Mark Rylance.

As to the Dickie/Richard dichotomy, he said, “It wasn’t a split personality. He had invented a persona of Richard Harris, a myth, and there was an awareness that he had done this at some level to the detriment, certainly from a career point of view.

“He fed the press with stories that they wanted, which was about his wild behavior and Rabelaisian life. And that was to the detriment of him being taken seriously as a creative force, as an artist.”

“He knew what he was doing but the price got heavier and heavier,” Harris said.

When he was introduced by Andy Williams at the Golden Globes in 1967 as “one of England’s most respected and honored stars,” Harris, in response, said to Williams that when he won awards he was English or British, but “every time I get into a fight” the headline is “Irish actor in brawl.”

He was a font of family stories for his sons, which were also told in long-form interviews in the media. “At a certain point,” Jared Harris said, “the press weren’t interested in that. They wanted the froth on top of the cappuccino. They wanted the wild life and the wild story.

“And they were funny, and they were crazy,” he added, “He had that thing that nutty things would happen. He put himself into situations where they could happen and he wasn’t frightened of them happening, and enjoyed it.”

He could be terrifying physically, as Stephen Rea and others attest in the film, but it seems not to have been the cause of a break with anyone interviewed here. Nor were artistic differences; the parting of the ways with two songwriter friends, for instance, had nothing to do with music.

Webb, who had a falling out with Harris over money and “material things,” regrets they were estranged for 20 years.

Phil Coulter wrote songs for Harris, whom he describes as a “force of nature” and “larger than life.” Of an American tour they did together, he says, “That was one adventure I would hate to have missed.”

But they never collaborated after the songwriter took issue with the militant nationalism embraced by the film star following Bloody Sunday.

“Believe me, the last thing the people of the north of Ireland want to hear is Richard Harris reciting a poem about the north of Ireland,” Coulter says in the film. He “wasn’t aware of the subtleties,” he says, and the situation was rather “more complicated” than he understood.

“His position would change on that,” Jared Harris says in the documentary, to the extent that the family required armed security after he condemned the Harrods bombing in 1983. Richard Harris himself is heard enumerating the death threats by mail and phone, and he refers also to the suspicious packages delivered at the theatre.

The actor would show his intense devotion for his homeland sometimes through rugby. On one occasion, he said he’d have given up all of his acting awards to have played once for Ireland.

By 2000, when Harris is seen joking with Peter O’Toole at England’s home ground Twickenham, the game had gone professional at the top levels. The rugby union of the Jesuit playing fields or anywhere else was strictly amateur in his time. The only way to go pro – and a schoolfriend said he was that good before his illness – was to switch to the long-time breakaway code called rugby league, the leading sport still in parts of the north of England.

And, in a sense, Harris did precisely that for his breakthrough role – the bruising rugby league player and ex-miner Frank Machin in “This Sporting Life.” The 1963 film, based on the novel by David Storey and set in a small city in Yorkshire, won him an Academy Award nomination and the best actor award at the Cannes Film Festival. It would be impossible now to ignore Richard Harris.

He was one of a key group of actors of stage and screen that were called upon to play the “angry young man,” a character type prominent in the “kitchen-sink dramas” of the era; another was Albert Finney.

It was an exciting time on the British stage, and a revolutionary one on the screen.

“He was part of the wave of optimism of the Sixties,” Jared Harris said.

The son has been a notable actor in an era that has seen huge transformations in film and television, not least the breakdown of traditional demarcation lines and hierarchies.

A recent success was his leading role as Valery Legasov in the 2019 historical drama miniseries “Chernobyl,” for which he received six best-actor nominations and two wins. Before that he won the hearts of viewers and the critics alike as King George in “The Crown.”

Harris considers himself fortunate to have had the opportunity a decade ago to work on Matthew Weiner’s “Mad Men” on AMC. He said it was a “brave person and a brave network” that undertook to do a series in which the character studies took precedence over the plotlines.

His character was Lane Pryce, who featured in Seasons 3 through 5 of the seven-season run.

“It's fascinating because what they’re selling is the American Dream to everybody, and the person [Don Draper] who is selling the American Dream is not who he says he is. He’s a phony,” he said. “Lane wanted to change. He’d been cast in the mold, the English, British mold. It was impossible for him to break free of it. But he wanted to be more like Don, he wanted to be more like these Americans who have this freedom to reinvent themselves.”

He said he knows a lot about someone when they tell him what they’ve seen him in, and it’s a long list by now. He’s particularly impressed when they cite “The Terror” (2018), as it’s a “very smart person who got that show and understood what it was about.”

Harris was taking character roles in big movies, like Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” (as Ulysses S. Grant), at an age when his father was doing films many feel ought to be forgotten. But he says it’s hard for someone to stay consistently at the top over decades.

“You have to admire the people who do,” Harris said. “Tom Cruise comes to mind.”

Still, his father was an internationally recognizable star over a time span of 40 years, one “who did great work throughout his career.”

And he conquered the music business. “One of the few actors to have done that,” the son said.

In Sibley’s film, Coulter declares “MacArthur Park” one of his favorite songs, adding that up to that point 2 minutes, 40 seconds, was considered the ideal for a single to get played on the radio; its composer Webb says it’s 7 minutes, 21 seconds.

It was a worldwide phenomenon, his son said.

Richard Harris was to finish his career strongly, with high-profile roles in “Gladiator” and the “Harry Potter” movies.

“I waited from 1957, when I got married to Elizabeth, until 1989 for the girl to arrive,” he said of his granddaughter, Ella Harris, who is at the center of his well-crafted story about why he signed up to play Professor Arbus Dumbledore.

“The hard life that he lived caught up with him in the end,” Jared Harris said. It didn’t help that the only exercise he got was walking from his room at the Savoy Hotel to the elevator and across the street to the pub, and back again. By way of contrast, his friend Sean Connery walked around the golf course five times a week.

The early part of the film tells the story of Harris’s death two decades ago and his sons’ responses to it over time. Jared Harris says the lights dimmed slightly after his passing, and “they’ve never really recovered.”

Damian Harris describes dreams so vivid he thinks his father is still alive when he awakens.

Towards the end, Jamie Harris sings “MacArthur Park” in the style of Richard Harris.

“As we get older, we are constantly reassessing our relationship with our parents,” Jared Harris said, and referring to the film, he added, “It’s part of that.”

For more information about the screening, go to thecraicfest.com.