James Patrick “Jim” Conroy was born in Dublin in 1897 and died in Southern California in 1981. His path early in life was typical of many of those from the upper-working class and lower-middle class who were the foot soldiers of the Irish revolution in the capital city. And in the finer details of it, Conroy’s closely paralleled those of others who were acolytes of Michael Collins; as it happened, he was present when the commander-in-chief was shot dead in an ambush in West Cork on Aug. 22, 1922.

What is not at all usual is that the man sometimes called “the Wild Chap” became the main suspect in two killings in late 1923 that had nothing apparently to do with the political events of the time.

The murders of Barnett, or “Bernard,” Goldberg and Emanuel, or “Ernest,” Kahn are discussed in Episode 3 of Brian Hanley’s podcast series “Dirty War in Dublin.” In the episode, writer and researcher Katrina Goldstone recalls interviewing the almost 90-year-old Esther Kahn on a number of occasions before tentatively raising the issue of her brother’s killing. “No, I can’t talk about this,” the elderly woman replied.

The first murder happened at 1 a.m. on Oct. 31, after Goldberg and his brother Samuel were accosted crossing Harcourt Street, close to St. Stephen’s Green. The dead man was a Manchester-based salesman for a jewelry company and visited his brother about three or four times a year. The 42-year-old husband and father was a “hugely respected and loved” member of the Jewish community in his resident city.

Nearby, two weeks later, the 24-year-old Kahn was shot dead and a friend, David Miller, wounded after leaving the Jewish Club at 3 Harrington St. This was closer to the heart of the Jewish Quarter centered around the South Circular Road and Clanbrassil Street.

Goldstone says, “For the community, ‘This is somebody who has come into our home and the center of our community and absolutely callously shot one of our members.’”

“The press were quick to emphasize that Kahn was a perfectly innocent man, never identified with politics of any description,” the narrator Hanley says.

Goldstone says that Kahn had an unusual job for a Jewish person in Dublin at the time, being a clerk in the Land Commission, a remove from the peddlers and dealers that so many in the community had been originally and still were.

A Garda report said the circumstances were so similar that it was the same assailants that were likely involved.

The Irish Times noted there was now an “uneasiness” within the Jewish community.

The Irish Independent editorialized, “We hope that our police forces’ efforts to track the midnight murderers will meet with success.”

In fact, one man, Ralph Laffan, was in 1925 found not guilty of the murder partly because he was so easily mistaken for his brother Fred Laffan, an army officer. He was charged with the lesser offense of wounding David Miller, but left the country before he was due in court in November, joining his brother Fred and Jim Conroy in Mexico.

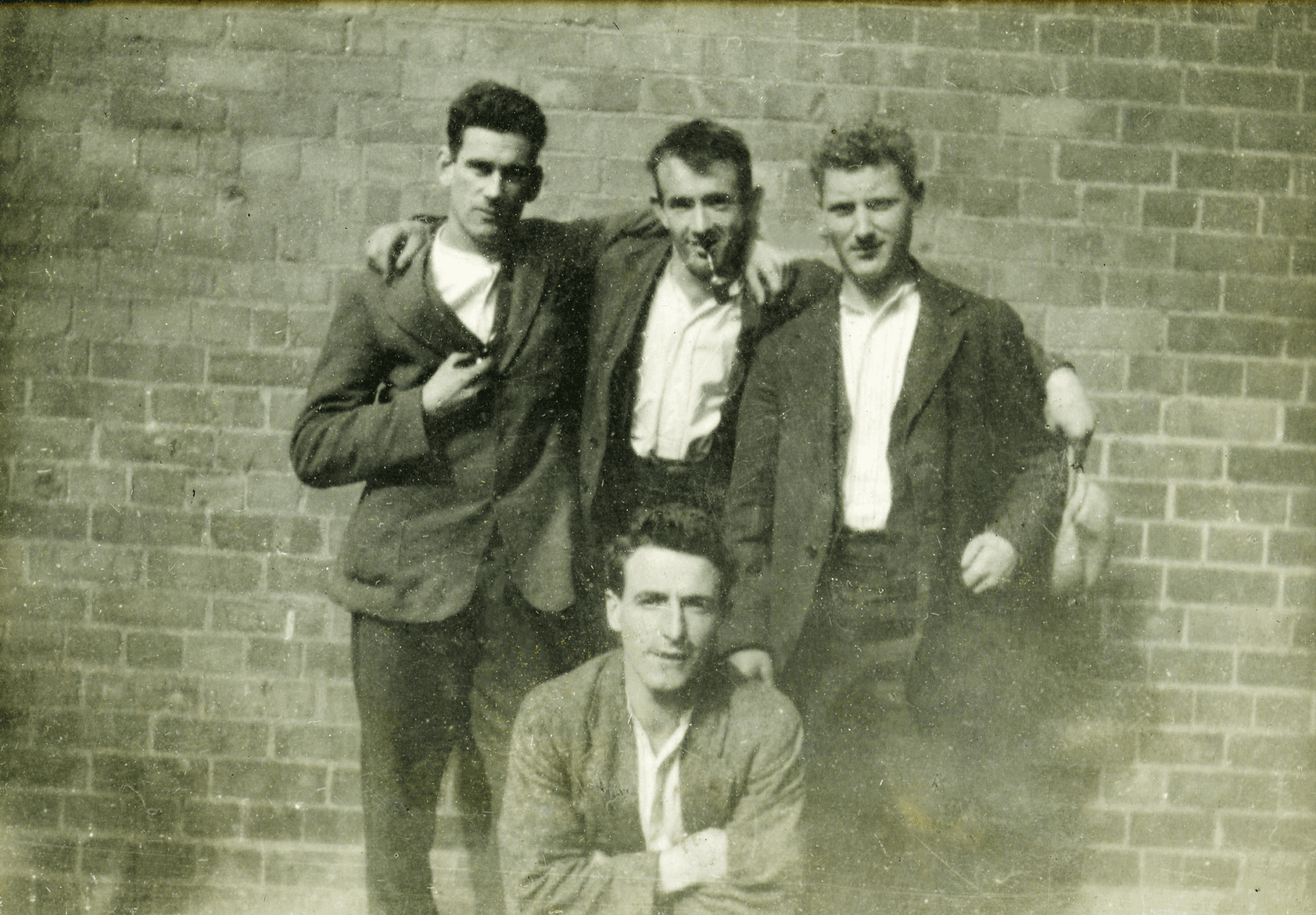

Conroy, considered the main suspect in the Kahn shooting, had a 10-year run in military activity beginning with the Howth gun running in July 1914. He saw action in the 1916 Rising (as did his father, a house painter of the same name), and was in 1920 recruited to “the Squad,” Collins’s hand-picked team of assassins. He was involved with several actions and plots, including, reportedly, a plan to rescue Kevin Barry, which was called off by the doomed medical student’s sister as impractical. He killed three RIC constables in an engagement in early 1921 and a British soldier in May and was involved in the attempt the same month to free Sean Mac Eoin, who was awaiting execution in Mountjoy Prison.

He was one of the 170 IRA members who invaded the Custom House in Dublin later in May and set it alight. The destruction of the landmark, the most ambitious action in terms of scale during the War of Independence, was Eamon de Valera’s idea, says the website “The Clock is Still Going” (customhousecommemoration.com), and it made headlines worldwide. However, it was ill-conceived from a military point of view -- the IRA hadn’t gone to fight, and close to 100 of the contingent were arrested. Collins hadn’t wanted his Squad and the full-timers in the Active Service Units involved at all in the action, and now many of his key men were interned.

During the occupation of the Custom House, Conroy had shot dead a 62-year-old caretaker and British army veteran, Frank Davis, who was attempting to get word out to the authorities via the telephone. When arrested, Conroy prudently gave an assumed name, Thomas Patrick Rigney. He was released on Dec. 8, two days after the signing of the Treaty. He joined the new National Army’s Dublin Guard shortly after Dáil ratification. We hear on the podcast how the young commandant reacted to the news that his father opposed the Treaty.

As indicated in Eoin Kinsella’s “The Irish Defense Forces: 1922-2022,” which was featured in the Echo recently, the pro-Treaty National Army was in part built around the Active Service Units and the Squad loyal to Collins. (Interestingly, according to “The Clock is Still Going,” six veterans of the IRA’s Custom House action in May 1921 are known to have been killed in fighting in the 1922-23 Civil War, and all of them were members of the government’s National Army.)

On Sept. 16, the month after he was witness to the Big Fellow’s death at Beal na Blath, Conroy was part of the convoy of troops that was halted by a large landmine near Macroom, Co. Cork. The attempt to defuse it killed seven soldiers, including his close friend and fellow Squad member, Col. Tom Kehoe, who was 23. Conroy is thought to have been involved in the shooting of an IRA suspect as a reprisal, and many regular troops demanded that the Squad members of the Dublin Guard be withdrawn back to the capital.

Conroy had various assignments as commanding officer and was in a separate unit, the Special Infantry Corps, tasked with intervening in social conflicts, such as the bitter war between farmers and farm laborers in County Waterford in 1923. But he was also likely involved in the “dirty war” incidents that are the subject of the podcast series.

With the Free State up and running, and the Civil War over, it was decided in 1924 that the country couldn’t afford such a large, unwieldy army. Conroy joined the IRAO army faction that resisted the plan to demobilize most of the soldiers; it lost and the Wild Chap left soon afterwards along with many comrades.

By this time, his name was being linked in police circles to the Kahn murder. Dublin Metropolitan Police Detective James Hughes, himself a former IRA intelligence officer, was in court in February 1924 for a case when he took a look in at another one in which Ralph Laffan faced a charge relating to an assault at a dance, and the cop noted a striking resemblance between the accused and Commandant James Conroy, who was testifying on his friend’s behalf, and the descriptions of those involved in the Kahn shooting. He passed on his suspicions up the chain of command, but was told to hold back on making an arrest.

Hanley suggests that there is a “little doubt” that his record as an assassin against both the British and the enemies of the new state “meant he had friends in the army and police and they would try to ensure he did not face justice.” Commandant James Fitzgerald was such a friend, one also with a record dating back to the gun-running; Goldstone’s impressive piecing of the case together shows how he helped.

In 1932, Conroy was confident that things had died down sufficiently and he returned to Ireland. There was a new government, however, and a minister, Sean McEntee, taunted the opposition by mentioning the Goldberg and Kahn murders in the Dáil; but nothing would be done. Kahn’s friend Miller had been silenced by a campaign of intimidation and was, in any case, compromised by his involvement in a road accident. He eventually left the country.

And so did Conroy, in 1936, after he secured his military pension. He lived in New York, where he was active in the 1916 Club, and he kept in touch with his old comrades from the Squad back home. After his wife’s death in 1968, he moved to California.

A number of motives for the murders are canvassed in the podcast. One is “blood lust,” as suggested by the prosecutor at Laffan’s trial; another is prejudice.

Hanley says, “Despite official protestations, antisemitism was pervasive and certainly affected how the crimes were viewed.”

Katrina Goldstone’s essay, “The Kahn/Goldberg Murders 1923 in Cultural Memory: Comparisons with Limerick 1904,” will be published later in the year in a book edited by Natalie Wynn and Sean Gannon, “New Perspectives on Limerick 1904.” For her website, click here, and for an article and Q & A in the Irish Echo upon the publication of her book, "Irish Writers in the Thirties: Art, War and Exile," click here. Brian Hanley’s “Dirty War in Dublin,” which has five episodes, is available on Spotify and other platforms.