Dan Barry is waiting for that tap on the shoulder, even after 28 years at the New York Times.

It would be from someone higher up, someone on the masthead perhaps, who would suggest that he might think about doing something else for a living. That this wasn’t working out.

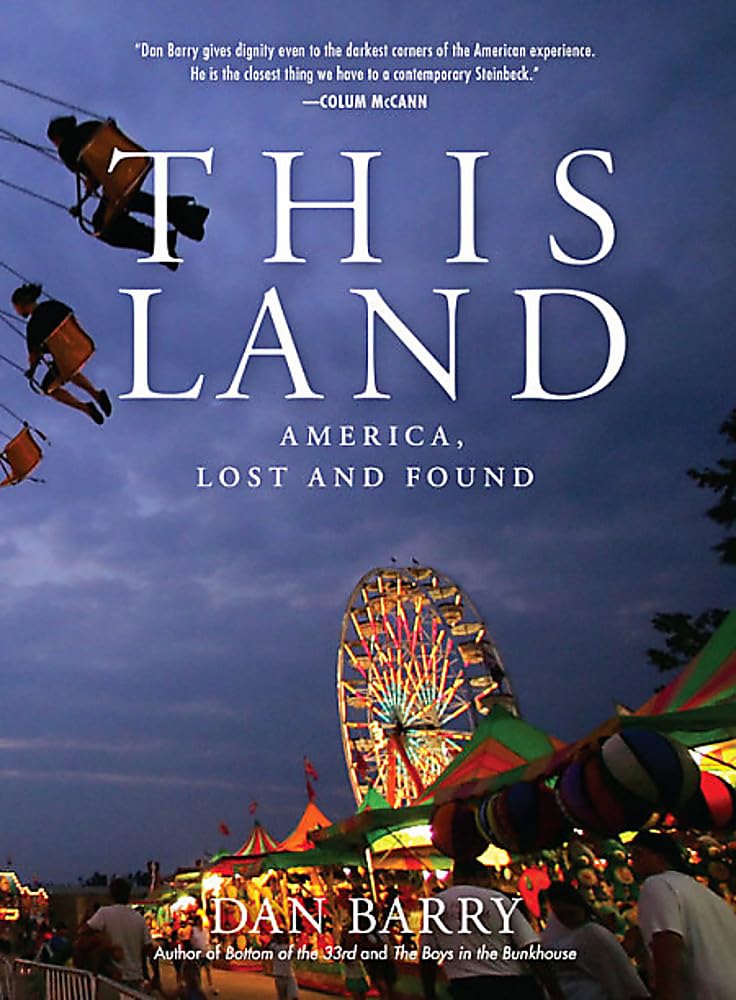

One might think Barry is joking, given that he is one of the paper’s highest-profile writers and famous for his long stints as columnist with “About New York” and “This Land,” in addition to being the author of five books.

But in a recent interview, he wasn’t. Or at least not really, in that he was giving expression to a past trauma.

Barry had been a month at the Providence Journal and was just about to turn 30, having spent the best part of his 20s at the Journal Inquirer, a daily based in Manchester, Conn.

“An editor called me into his office and he said I should wonder about another career, that I wasn’t doing very well.

“I remember calling my future wife, Mary Trinity, late that night, and she remembers it better than I do,” Barry said. “I was devastated.”

The 2023 recipient of the Eugene O’Neill Lifetime Achievement Award (to be presented this Monday by the Irish American Writers & Artists) didn’t think he was doing so badly. “I was definitely enthusiastic. I’d been good enough to be hired at this rather larger newspaper,” he said.

“And so that was a real reckoning for me. It filled me with doubt. Then, after the doubt came a resolve to do better.”

Still, as he’d believed he had been doing well, now he had to figure out why his efforts weren’t to that editor’s satisfaction.

“I think I may have blown a deadline. But no one had thought to tell me what the deadline was because I was relatively new,” Barry said. “Also, my writing style was not straight forward all the time. On the one hand, that might be engaging to people, on the other, for an editor, they just want ‘who, what, when, where, how, why.’ Perhaps, there was a little bit of that. I was trying too hard to be distinctive in my writing.

“It taught me, A. You can’t miss a deadline, those are sacrosanct, and B. You shouldn’t always try to be William Faulkner on deadline,” Barry said. “You want to convey the information to the reader, and then try to do it in an entertaining and elucidating way.

“There’s a balance there. I’m still learning to find that balance,” he added.

Barry revealed there is a legacy of “constant doubt, constant second guessing and always trying to get better.”

The native Long Islander would soon thrive in Providence and become part of a Pulitzer Prize-winning team. But his real apprenticeship was with the Journal Inquirer. “It was always competing with the Hartford Courant, which was the big newspaper in Connecticut. We were a bulldog newspaper, always nipping at their heels and trying to beat them. And we often did.

“There was an esprit de corps there that was powerful,” he said.

Barry still gets together twice a year with colleagues from that time.

“You’re being formed as an adult and those relationships you form at that stage oftentimes can be lifelong,” he said.

“Towards the end of my time there, one of my colleagues was murdered in her apartment. It was like someone in our family, and our small newspaper rallied together and leafleted the area, and tried to help the police as much as we could,” he said.

Barry was the lead reporter for the paper on the case. “I deluded myself into thinking ‘I’m going to solve this case and find the killer.' And that was a delusion,” he said. “But the loss brought people together as well.”

The move to Providence was an interesting shift up in scale, which brought with it the inevitable larger-than-life personalities, among them the police night editor who owned a bar called Hope’s. Folks assumed it was inspired somehow by Rhode Island’s motto, which is “Hope.” It wasn’t. The name referenced Harry Hope, the saloon-owner protagonist in O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh.”

At the time, the night shift would end at 1 or 2 o’clock and the bars were supposed to be closed by 2.

“This place would stay open,” Barry recalled, “They’d pull the shades down, dim the lights, and all the night reporters and the night editors would be there ‘til 4 or 5 in the morning, just shooting pool and telling stories about newspapers.

“So, it was filled with characters. Today, the deadline is always now, because we’re in a digital universe. Back then, the Providence Journal owned two newspapers, there was an afternoon paper and there was a morning paper.

“You couldn’t blow a deadline. Sometimes in the digital era you have a few more minutes. As long as CNN doesn’t have it before us, we’re okay,” he said. “Back then, you couldn’t, because the paper had to be delivered to Woonsocket or West Warwick or wherever it was in Rhode Island.”

He continued, “The camaraderie was really great. It was like a gang of misfits, all of them in their own way socially challenged, yet they shared the love of the word and the love of the story, and busting balls of people in power.”

Barry’s most notable story, or series of stories, was written as part of the team that exposed corruption in the courts system in Rhode Island, and that led to the Pulitzer for Investigative Reporting in 1994.

Winning a Pulitzer at a regional paper was a different process than for a publication like the New York Times, which would get advance notice, in part because of its clout, but also because it might have to get a reporter back in place from foreign parts for a celebration. The Journal guessed it might have a shot at the investigative category and assumed it would get word unofficially if the prize was indeed going its way. When that word hadn’t come, individual team members, their working day finished, left the office dejected. Barry stayed on to finish a project.

“Suddenly the photo editor of the Providence Journal stood up and started clapping. People had thought he had lost his mind,” the journalist said of a colleague who spotted the news come in over the wires. Others gathered around him and started clapping, too.

“It was pretty extraordinary,” recalled the only member of the winning team still at the office.

Another scaling up took place a year or so later, through “luck and happenstance,” when he joined the New York Times.

Now millions of people, nationally and internationally, could be reading his stories.

“The first time, I felt the gravity of that, that every choice of word would be read far from the newsroom in Midtown Manhattan,” Barry said. “It kind of paralyzed me for a few minutes.

“And then what happens is the pressure of a deadline has a way of clarifying the mind and you just get on with it.”

Barry recalled of his first weeks at the paper, “Walking around the newsroom you would recognize the bylines and see the person behind the bylines.”

Johnny Apple, John Kifner, Maureen Dowd, Francis X. Clines, Clyde Haberman. They were journalistic gods to him, and became no less so when he saw human beings at their keyboards.

“I’d just be in awe that I was among them,” he said. “It was a six-month probation period and you’d live in abject terror that you wouldn’t cut it.”

The year Barry joined the Times, it used color photography for the first time on the front page.

“There were people saying, ‘This is ruining the New York Times!’” he said.

“Garish!” was one single-word critique of the new look.

In this context, he mentioned that his colleague Adam Nagourney has just published an account of a revolutionary period: “The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn and the Transformation of Journalism.”

“The New York Times has figured out a subscription-based model that has worked and also they figured out how to monetize other features,” Barry said,

That money goes to support, for example, Tyler Hicks, a photojournalist who’s risking his life in Ukraine.

“The thing about reading the newspaper in print – it’s a different art form,” he said.

“It’s an honored and beautiful thing, and I know people who’ve dedicated their lives to the print format. And I’ve benefited from some of their art with my own stories.

“Also, with a newspaper that you hold you’re open more to serendipity," Barry said, “You go to A11, and there’s another story you hadn’t known about in the corner and you read that and something goes off in your mind, some kind of lightbulb. There’s a moment of illumination right there.”

But while he misses, as much as anyone else, the “rumbling of the printing presses,” he is an enthusiast, too, for the "fresh and exciting" journalistic benefits of the digital age thus far, and their presentation is "also an art form."

Communications generally have come a long way since Noreen Barry made her Sunday phone call to the grocery in Gort with her sister Chrissie waiting on the other end, at the prearranged 2 p.m., Ireland time.

Having a mother who came to America as a teenager from rural County Galway in 1952, one who never became an American citizen, meant that Dan Barry could never escape his Irishness.

“Try as I might,” he added good-humoredly about that close tie.

There was a “great love for Ireland but not romance. It was what it was.” (See this 2021 Times piece about his family and Galway.)

There were Clancy Brothers albums, the volume of Irish history on the book shelf and the aunt, the sister of his grandmother, who would stay half the year.

Barry said, “We also know we’re not Irish, my siblings and I. We’re Irish citizens through our mother, but Americans tend to blur the lines. I’m Irish American, or American Irish, and that’s a different thing [to being Irish].”

Barry’s father was a second-generation Irish-American from Brooklyn. “A very bright guy, self-educated,” his son recalled.

The journalist said of his parents, “They were complicated and flawed and maybe drank too much at times, but they tried. That’s all you think about in the human existence is you try.

“They never gave up.”

He has always been drawn to telling the stories of such people, not the stars like Mother Teresa or Rudy Giuliani.

“They’re trying to get by and they’re trying to take care of their kids. And trying not to offend their neighbors,” he said.

And in telling their stories, he feels he is honoring them as people.

As for Barry’s own upcoming honor, a lifetime achievement award, he said, “I don’t feel worthy.”

He asked Maria Deasy, the president of the Irish American Writers & Artists, “Are you sure? You can reconsider and get back to me.”

The IAW&A was sure and is sure, and Dan Barry will happily accept on Monday evening.

Dan Barry will receive the 2023 Eugene O'Neill Lifetime Achievement Award from Irish American Writers & Artists on Monday, Oct. 16, at the restaurant 5th & MAD, located at 7 East 36th St., in Midtown Manhattan. The event begins at 6:30 p.m. and will continue through 9:30 p.m. For tickets and further information, go the website here.