“We knew all about him, always.”

So said Helen Mulcahy about an uncle killed far away in New York, 107 years ago.

The memory of Patrolman William McAuliffe’s passing may have faded over time in his precinct on East 67th Street and the surrounding neighborhood, but he would forever be held in high esteem in his home place, near Blarney, Co. Cork.

“My mother was very proud of him,” Mulcahy recalled. “And my grandmother.”

Her grandmother’s Uncle Willie was honored last Saturday morning at a street co-naming ceremony on Second Avenue at 67th Street, just a few feet from where he was gunned down by an unknown assailant on the night of March 18, 1916.

At a gathering later at the 19th Precinct to mark the inauguration of Patrolman William McAuliffe Way, his great-grandniece remembered the “old photo in an old frame” at home.

“He was held up as a model,” Mulcahy, a County Cork resident, said of the slain policeman.

In the preparation for the street co-naming, the 19th Precinct’s Detective Anthony Nuccio asked in an online post if anyone knew of McAuliffe relatives. “Little did he know how many of us there are,” Mulcahy said, referring to the strong turnout of kin from Cork, New Hampshire and Canada on last Saturday morning. Most seemed to have been descended from Willie’s brother Jeremiah, who stayed at home in Ireland, and who with his parents received the terrible news of the murder in New York in the days after March 18.

Four of the family’s seven siblings made their lives in New York City, and three of them, including the patrolman, who left Ireland in 1902, were buried in a family plot in Calvary Cemetery in Woodside.

Helen Mulcahy thought it a “lovely” event. "It was great and it was very nice that the dignitaries were present," she added.

The moment declaring Patrolman William McAuliffe Way at 67th Street and Second Avenue. [Photo by Peter McDermott]

Deputy Inspector William Gallagher, commanding officer of the 19th Precinct, revealed that many serving out of the 67th Street building today are immigrants, just as Patrolman McAuliffe had been. “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” he said.

Council Member Keith Powers, a member of the Irish caucus on New York City Council, commended the officers’ crucial role in keeping the neighborhood “safe and beautiful.”

Deputy Consul General of Ireland Gareth Hargadon, the son of a retired member of An Garda Síochána and the brother of a serving member, spoke of his awareness of how “increasingly difficult” it is for police officers to do their job.

Patrick Hendry, the president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, welcomed the move that saw McAuliffe finally getting his recognition. “He was a true hero who paved the way for us all,” he said.

The rain that had battered New York City in previous days continued through the start of the 11 a.m. ceremony, which began under a tent; but conditions eased markedly for the open-air part of the proceedings, including the unveiling of a new street sign with Patrolman McAuliffe’s name on it and the taking of photographs.

Weather figured prominently in the report of McAuliffe’s murder in the New York Times the next morning. The patrolman, most of the winter, “had been detailed to do traffic work with the gangs of snow shovelers, and had been continuously engaged at this work for more than a month till he was sent back to his post Friday night.”

A separate article in the March 19 edition noted that the month had been “unusual for cold and snow.” The Times said the day before was the coldest March 18 since the Weather Bureau records began in 1873, and the day before that was the coldest St. Patrick’s Day since 1900; indeed, it was 20 degrees colder than usual. The average for March 18 was 35 degrees, with the average minimum for the day being 28 degrees. At 5 a.m. on the last day of William McAuliffe’s life, it was 6.6 degrees.

“Since he was shot on his second night at routine duty,” the paper said, “it is believed that it may have been done by some one who had been waiting for him to finish the special detail.”

The Times said, “McAuliffe, who lived with his brother at 306 East Forty-fourth Street, was 35 years old and had been on the force six years. His record had been excellent, he was generally liked by the people on his post, and he had no troubles with any one so far as is known.” (The home address is today half a block from the United Nations Headquarters.)

© The New York Times.

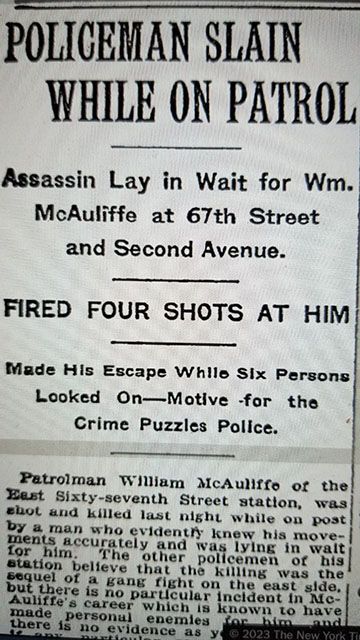

The opening paragraph of the report said the patrolman was killed by “a man who evidently knew his movements accurately and was lying in wait for him.”

It continued, “The other policemen of his station believe that the killing was the sequel of a gang fight on the east side, but there is no particular incident in McAuliffe’s career which is known to have made personal enemies for him, and there is no evidence as yet as to what, if any, particular gang the murderer belonged to.

“At 9:53, McAuliffe called the station from the police telephone box at Sixty-eighth Street and Second Avenue. Then he turned south on the avenue and walked to Sixty-seventh Street. He arrived there not more than three minutes after he hung up the telephone receiver, and when he reached the corner a short, dark man who was waiting in the gutter for him drew a revolver and fired four shots. Two shots entered the policeman’s back and the other two went wild.”

A civilian called the station and “reserves were sent out at once”; a Dr. McCullum “took the policeman to the hospital but he died in the ambulance without regaining consciousness.”

The murderer was seen running east via an empty lot.

“The police found six witnesses of the shooting and questioned them closely but none was able to give a clue as to the identity of the murderer,” the New York Times’ report continued. “The scene of the shooting was on the lower edge of the Bohemian quarter, where crimes of violence are comparatively rare. [“Bohemian” in this context meant Czech.]

“It is the theory of the police that it might have been done by a gangster from the lower east side, who had come uptown or by one from East Harlem who had come downtown,” the Times said, “or by some one from the Italian district a few blocks below.”

The Times referred to “two agglomerations of thugs,” both long-time named gangs in the area, presumably comprised of native-born New Yorkers mainly, but they had been “broken up in recent years,” and the police and media seemed to be pointing instead to an immigrant suspect with their references to the Lower East Side, which was predominantly East European Jewish, and the heavily Italian East Harlem.

For good measure, the Times noted, “About nine months ago, Patrolman Michael Egan of the same precinct was shot in the face and severely wounded by an Italian at Seventy-second Street and Second Avenue.”

Detective Anthony Nuccio of the 19th Precinct and Inspector Bridie O’Reilly of the Auxiliary NYPD pose beside a portrait of Patrolman William McAuliffe at the precinct on East 67th Street. [Photo by Peter McDermott]

The report ended with, “Deputy Police Commissioners Frank Lord and Guy H. Scull and Detective Inspector Joseph Faurot went up from police headquarters as soon as they heard of the murder and began examining witnesses at the East Sixty-seventh Street Station.”

Their investigations led nowhere, it seems. The Officer Down Memorial Page, odmp.org, describes the perpetrator in this case as “at large.”

Meantime, at the precinct, which is between Lexington and Third Avenues, Inspector Bridie O’Reilly of the Auxiliary NYPD deemed the event a “beautiful” one. The immigrant from County Sligo had assisted Detective Nuccio in getting the word out and with other aspects of the planning.

The large McAuliffe contingent was happy, too. And the weather stayed calm; so next up was a pilgrimage to the plot in Calvary.