An outsider looking at Ireland’s hundred years of independence would surely be astonished by the gradual transition from rags to riches.

The country started off in dire circumstances: the treasury was very low and business activity was stagnant. Lenders were hard to find for a nascent economy among European countries, or in Washington where what came to be known as the Great Depression was already beckoning.

Even worse than the economic challenges, political differences loomed dangerously large. The vote to accept the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty showed a major cleavage in the Dáil with almost half of the TDs, led by the president of the assembly, Eamon de Valera, condemning the deal as a sellout of Republican principles.

In particular, they strongly resented the requirement that members of the new Free State parliament would be compelled to sign an oath of fealty to the English monarch. This was the driving issue of the Civil War.

The days following the formal establishment of the new parliament in December 1922, with W. T. Cosgrave as president, were marred by outrage and tragedy. Two government TDs were gunned down by Republicans on their way to work in Leinster House and, the following morning, in reprisal, four senior anti-treaty leaders incarcerated in Mountjoy prison were executed by the government without even being charged before a court or a military tribunal.

The civil war finally ended in May, 1923 when Republicans dumped arms and accepted the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The majority of the former rebels supported de Valera’s party, Fianna Fail, and he was elected prime minister in 1932 and successfully held that position for most of the next four decades.

Donogh O'Malley.

Bitterness and division defined the first fifty years of independence. The grievances of both sides were nursed through generations – admittedly with less stringency as time moved on. Today, the descendants of both civil war parties share government power in a coalition arrangement in Dublin.

Commercial policy in the early years of independence was based on promoting indigenous industries which never provided sufficient work for the big families all over the country. Tens of thousands of young people emptied from the country to England, Australia and especially America, so providing a safety valve in an otherwise explosive situation.

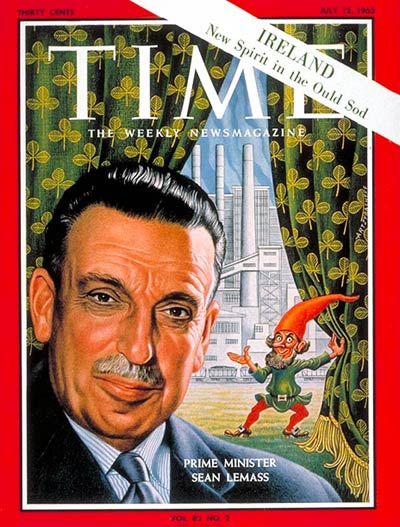

The sixties ushered in an era of change all over the world. In Ireland, de Valera’s successor, Sean Lemass, a 1916 veteran, is remembered as a smart promoter of strategies that focused on alluring foreign investment to Ireland.

The Industrial Development Authority (IDA) assumed a central role in government planning as they sought to entice established companies to move part of their production to an English-speaking country with a relatively educated workforce.

This policy has been a stupendous success, especially since Ireland joined the European Union (then the European Economic Community or EEC) in 1973. Today, over ten percent of Ireland’s workforce is employed in the multinational sector, particularly in big technology corporations and with drugs producers. These Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) have come through the pandemic relatively unscathed.

Just how exuberant employment is in the FDI sector can be gauged from the IDA announcement that in 2021 the increase in employment numbers came to 16,800, almost double the figure for the previous year.

During the Home Rule debates in the early twentieth century the Unionists in the North warned repeatedly that Home Rule would amount to Rome Rule. They suspected that in a state dominated by Catholics the bishops would exercise excessive power, which would mean that Protestants would be shunted aside from the special treatment they were accorded under British rule.

How did this apprehension work out when nationalists took over in Dublin a hundred years ago? Their fears were largely justified and the Catholic hierarchy, led by Archbishop McQuaid of Dublin, called the shots. No political party dared take them on.

In 1979, for instance, the Minister for Health, Charles Haughey, was tasked with coming up with a bill that would allow for the limited availability of contraceptives for married couples. He was walking a tightrope because the hierarchy made no bones about preaching about the evils that would follow easy accessibility of the contraceptive pill.

Mr. Haughey, a masterly politician, started by praising natural family planning groups and pointed approvingly at the fine work being done by the National Association for the Ovulation Method. However, his bill did allow married couples to purchase contraceptive items except when prescribed by a doctor and dispensed by a registered chemist.

Less than forty years later the Irish people, in a stunning reversal, approved legal abortion and gay marriage in separate referenda.

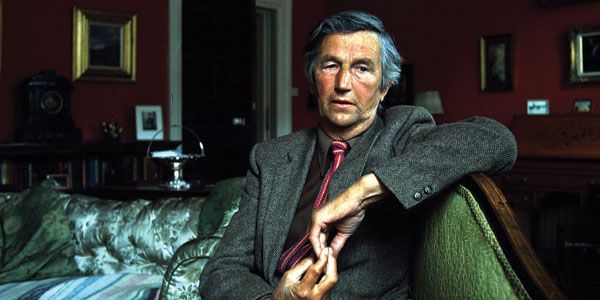

Dr. Noel Browne.

One of the most shameful examples of church control happened in 1949 at the burial services for the first president of Ireland, Douglas Hyde, who was a member of the Church of Ireland. The prayer service was held in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. Government ministers, all from the majority religion, were forbidden to even enter a Protestant church, so they, with the exception of Noel Browne, who did attend the service, were photographed outside the church waiting for the cortege to emerge.

The scandal of clerical sexual abuse of children in industrial schools combined with the maltreatment of women in the loathsome Magdalene laundries has besmirched - more than anything else - the story of the Irish century of independence. The unchristian, class-ridden culture, driven by the power games played by church and state, caused these awful abuses and remains a sad commentary on the first hundred years.

In the mid 1960s the Minister for Education, Donogh O’Malley, introduced free education at secondary level in Ireland. This was a hugely important progressive decision. Third level institutions also gradually opened their doors to a wider clientele. Today public investment in colleges, universities and training centers matches any western country – a major achievement.

Policing policies have also contributed greatly to Irish development. The bitterness of the civil war years could easily have spilled over into recriminations and rowdiness, but the new police force, the Garda Siochana, an unarmed constabulary, performed their duties in an exemplary fashion and earned the respect of the entire population.

De Valera successfully maintained Irish neutrality during the Second World War, a considerable achievement considering that the neighboring island was a main combatant.

Ireland joined the United Nations in 1955 and its representatives have been elected four times to membership in the Security Council, the latest of these two-year terms ending at the end of 2022. The recent tragic death of Private Sean Rooney, while on peacekeeping duties in the Lebanon, highlights the country’s commitment to the UN’s policy of ameliorating war situations around the world.

Ireland never flirted seriously with fascism, although other European Catholic countries, like Spain and Italy, embraced the notion of rule by strongman dictators. While Republicans dubiously rejected the legitimacy of the Dáil vote supporting the Treaty on January 6th 1922, nearly all their leaders clung to the idea that the will of the Irish people had to be the guiding principle of democratic government. To this day that commitment supersedes all other considerations in Irish elections.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com