With the Passing of Queen Elizabeth, so too should the myth of the “Special Relationship.”

Within minutes of the announcement of the death of Queen Elizabeth, the internet was flooded with stories bearing headlines about the Queen and what the passing would mean for the "special relationship."

The "special relationship" is a diplomatic shibboleth that must be invoked like a political "knock on wood" whenever the United Kingdom is mentioned on Capitol Hill. Currently, in congress, there is legislation (S.4450) entitled the" Special Relationship Act."

Senator Chris Coons.

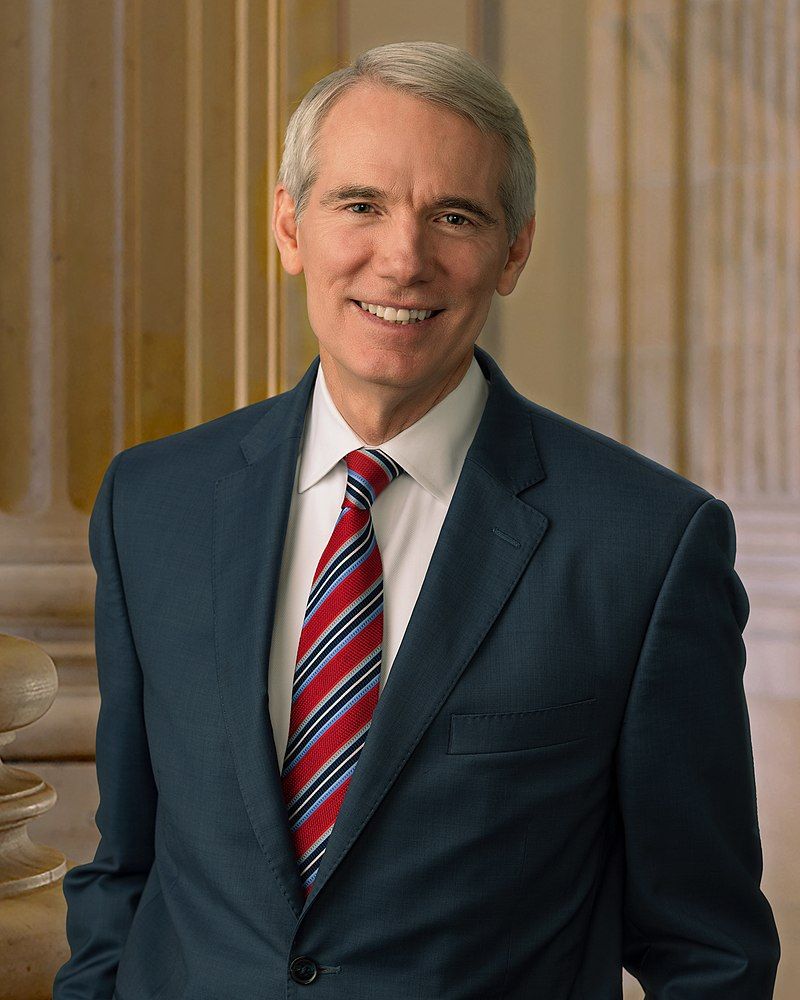

So entrenched is the term "special relationship" in the Washington lexicon that the authors, Senators Rob Portman and Chris Coons, felt no need to define who the subject/beneficiary of the" Special Relationship Act" is in the title.

The unasked question is, why is the U.S./U.K. relationship so "special" that it should be implied to have pre-eminence over other international relationships?

Senator Rob Portman.

While often discussed in historical terms, the special relationship is, is in fact, younger than the late queen.

The United States was born from the failure of the relationship between the United Kingdom and its colonies. The relationship between the United Kingdom was not special when they went to war in 1812. It was not a "special relationship" when the U.K. legally recognized the belligerent status of the Confederacy in its conflict to preserve slavery or turned a blind eye to the shipment of arms to sustain its efforts. Yes, we did fight as allies in two World Wars (along with many other nations).

The birth of the term "Special Relationship" actually traces its roots to Winston Churchill's "Sinews of Peace Address," often called "the Iron Curtain speech," delivered on 5 March 1946.

Churchill said, "Neither the sure prevention of war, nor the continuous rise of world organization will be gained without what I have called the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples... a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States."

The reference to the "British Empire" should raise a flag as to how relevant the claim of a "special relationship" is today.

That empire would end a year later with the independence of India. Ironically, today, as Charles III ascends the throne, there is growing concern about how long the Commonwealth will last, if not the United Kingdom.

The fact that the "special relationship" is used in the same speech where the term "Iron Curtain" was coined is no coincidence.

As the leader of a crumbling and bankrupt empire confronting an increasingly powerful and aggressive Soviet Union, Churchill was deploying his last and arguably best weapon: his command of language. The "special relationship" was born, but it's a testament to Churchill as a marketer rather than historic fact.

Further examination of the basis of Churchill's "special relationship," the "the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples," is more uncomfortable; the "the fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples " being a transparent euphemism for "we Anglo Saxons must stick together."

All this would be simply grist for the mill of historical debate if it were not for the fact that the myth of the “special relationship" is used today to justify actions on the part of the United States which should require more critical examination, such as brokering a new trade deal with a partner that has a poor record of honoring its commitments.

Nearly 25 years on, the United Kingdom has yet to keep many of its obligations under the Good Friday agreement, even something as innocuous as recognition of the Irish language.

Currently, it is seeking to escape its responsibilities under the Brexit agreement it signed only two years ago. Most outrageously, legislation before Parliament would grant an amnesty for the actions of British soldiers and intelligence forces for criminal acts committed during the conflict in Northern Ireland. Such an action would loudly be denounced if enacted by another country not shielded by the mythos of the "special relationship."

We should not let the bonhomie puffery of an alleged "special relationship" preclude us from critically examining every dealing with every nation and applying a consistent standard.

Queen Elizabeth was the last monarch to be born during the British Empire. Her passing represents the closing of a chapter of history.

The "special relationship," like the pomp of the late queen's funeral, is nostalgia for a time that no longer exists. It is time to consign it likewise to history rather than used to guide to formulate current policy.

The writer is National Political Education Chairman for the Ancient Order of Hibernians.