Cathal Brugha was shot during fighting in Dublin at the outset of the Civil War and died at the Mater Hospital the next morning, July 7, 1922. He was 47 and left behind a family of six children, from 9 years down to three months.

His widow Caitlín requested that government representatives stay away from his funeral.

The head of that government, Michael Collins, said in tribute: “Because of his sincerity I would forgive him anything. At worst he was a fanatic – though in what had been a noble cause.”

The unionist Irish Times praised his “magnificent gesture of tragic defiance.”

When Harry Boland was shot a few weeks later, his dying words to his mother and sister were: “I am going to Cathal Brugha…I want to be buried in the grave with Cathal Brugha.”

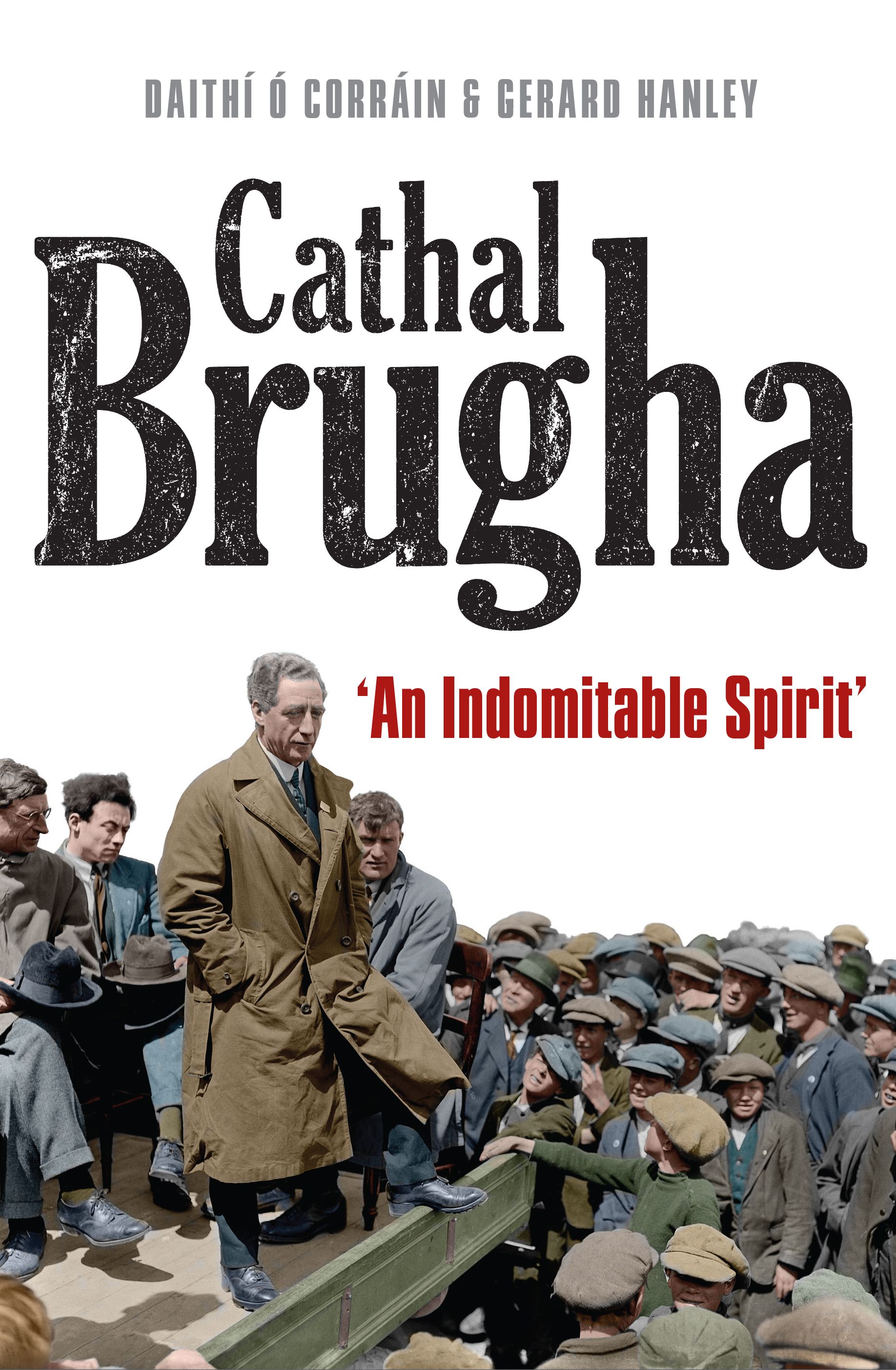

Dublin City University's Daithí Ó Corráin said his book “Cathal Brugha: ‘An Indomitable Spirit,’” co-authored with Gerard Hanley, “reappraises the life and revolutionary career of Cathal Brugha. Hundreds of books have been written about the Irish Revolution. They all mention Brugha in passing but without ever offering a detailed examination of his contribution, which by any measure was extraordinary.

Daithí Ó Corráin.

“He was a member of the Gaelic League, Irish Republican Brotherhood and Irish Volunteers; a celebrated survivor of the 1916 Rising, despite multiple gunshot wounds; a crucial figure in the post-Rising reorganization of the Volunteers and Sinn Féin; speaker at the first sitting of Dáil Éireann and president pro tempore; minister for defense in the underground government during the War of Independence; passionate and acerbic opponent of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921; a reluctant participant in the Irish Civil War, having tried to prevent it, and that conflict’s first high-profile fatality in July 1922.”

Added Ó Corráin, a GAA enthusiast still “buzzing” when the Echo was first in contact in August, weeks after Kerry’s winning the All Ireland final, “This new study provides a multi-layered reappraisal of an important but severely neglected and often misunderstood figure.”

The authors write, “There has been a tendency to reduce Brugha’s contribution to the Irish Revolution to a three-act melodrama of soldierly acts of heroic defiance in 1916 and 1922, and furious ad hominem attacks on Collins and [Arthur] Griffith for betraying the republic by signing the Anglo-Irish treaty and accepting dominion status.”

They seek to contest the prevailing view of their subject as a “martial” figure primarily, when in fact he was both a constitutionalist and a militant.

Even after the Dáil had, in the authors’ words, “effectively disestablished his cherished republic” by backing the Treaty, Brugha still believed it retained its authority and primacy, something that many miss and indeed sometimes suggest the opposite, as in the case of a recent RTE documentary.

It's certainly true, in the words of historian James Quinn, that “even in a movement of zealous men and women, Brugha’s zeal was exceptional.” But Ó Corráin and Hanley want to correct the picture of him a “dour, sour, uncompromising, antagonistic, ruthless zealot such as that portrayed in Neil Jordan’s 1996 film, ‘Michael Collins.’”

Charles William St. John Burgess, was born on July 18, 1874, at 13 Richmond Ave., Dublin. He was the third son and 10th of an eventual 14 children of Marianne and Thomas Burgess. Marianne was the daughter of an auctioneer, Edward Flynn, while Thomas’s father was one of three brothers, all craftsmen, who’d left Borris, Co. Carlow, for Dublin in the early 19th century. The Burgess family was Protestant, but Marianne’s 14 children were raised in her Catholic faith.

Thomas was listed in Thom’s Directory at the time of Charles’s birth as an importer and valuer of works of art and decorative furniture at his business in Nassau Street; and the same year the family moved to a more substantial residence at 29 North Frederick St.

“Although Ireland was relatively tranquil demands for change in the domains of political status, land ownership and cultural identity intensified in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” the authors write. “Five months before Brugha’s birth, 70 Home Rulers were returned at the February 1874 general election with the political goal of restoring an autonomous Irish government.”

Thomas Burgess became an admirer of the leading Irish parliamentarian, Charles Stewart Parnell, in the increasingly turbulent 1880s. All was not well on the domestic front for the Burgess family, either, as the decade came to a close. Charles’s older brothers, Edward and Thomas Jr., accompanied a large shipment of pictures, furniture and statuary to Sydney, and due a combination of mismanagement and chicanery sent no cash home. “Ruined by his sons in Australia” went one headline in that country.

Cathal Brugha, the authors say, as an adult “developed an abhorrence…of financial impropriety and was sometimes accused of parsimony in both his business and political life.”

The financial situation impacted the younger children’s education, the girls being withdrawn from boarding school and Charles and his younger brother Alfred’s attendance being disrupted at the Jesuits’ Belvedere College.

In his youth, nonetheless, Charles attracted news coverage for his athletic prowess. He excelled competitively at swimming, gymnastics, cricket and rugby and also boxed, was a cyclist and played hurling and Gaelic football. Later, though, he indicated a preference for those last-named “native” games over the more “Saxon” pursuits.

A good all-round student, with a particular passion for Irish history, Charles completed two years at medical school, but his father’s declining health and the family’s straitened circumstances were factors in his taking a business path. In his 27th year, he was listed in the 1901 Census as a commercial traveler. By the 1911 Census, he was Cathal Brugha, having previously experimented with some other Gaelicizations of his family’s name.

Caitlín Kingston, whom he met in her hometown branch of the Gaelic League, was similar to him in background and views: her family owned a business in Birr, Co. Offaly, which she’d helped her mother run upon her father’s death, and she was as intensely religious and nationalistic as he was. The Gaelic League was a respectable social outlet for the English-speaking middle-class; it was where Brugha’s future 1916 commandant and close friend Éamonn Ceannt and his future political leader Éamon de Valera also met their spouses.

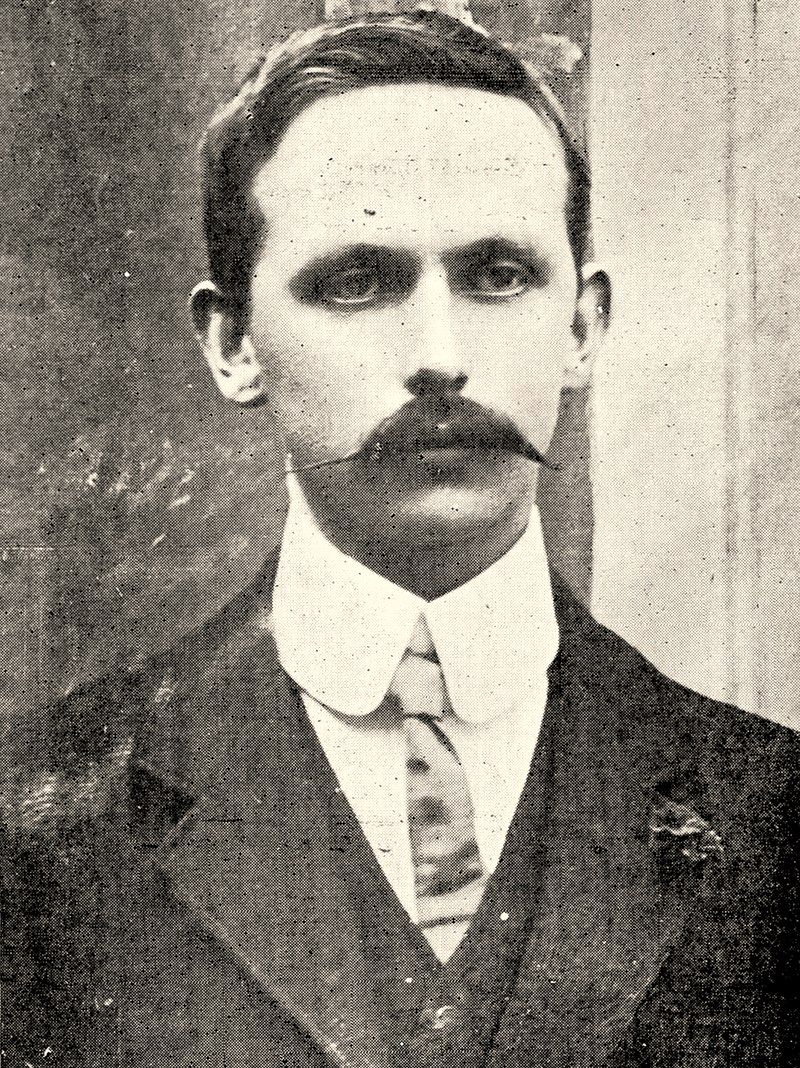

Cathal Brugha.

His own Keating branch in Dublin vigorously promoted the Munster dialect over the Connacht, and Brugha was a frequent visitor to Waterford where he could eventually pass as a native speaker (he was elected as Sinn Féin TD for the rural part of the county in the December 1918 election).

The branch had overlapping membership with the Teeling circle of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (including several notable personalities who would later support the Treaty, some of whom he saw as constituting a cabal).

Brugha joined the IRB in 1908, and in 1909, he formed a company, Lalor Ltd., with two brothers of that name, which manufactured church candles and supplied allied products. He would remain a working director of the company until his death; during the War of Independence he managed his ministerial portfolio from its factory at Lower Ormond Quay in Dublin.

The heroic and very competent defense of the South Dublin Union garrison during Easter Week by Ceannt, who was executed subsequently as a signatory of the Proclamation, and Brugha, created a “formidable aura” around the latter.

Éamonn Ceannt.

And he would always be for some, in the description of a contemporary, “A hard-featured little soldier with firmly set mouth [and] piercing eyes.”

Brugha wasn’t put on trial or even incarcerated after the Rising. After months of hospitalization, he was delivered home on a stretcher by two soldiers, who were each offered a glass of whiskey as thanks.

Meanwhile, IRB networks were being built in Frongoch internment camp and in prisons, with Collins at the center. Brugha, like de Valera, had opted out of the secret organization, which became central to the drama around conflicts within the independence movement.

Brugha’s relationship with Collins, which started out as friendly, is examined in detail here. They were a contrast in opposites: the reserved Dubliner didn’t smoke, drink or swear, while he attended Mass and said the Rosary daily; the extroverted West Cork native, who dominated every room he was in, did smoke, drink and swear, a lot, and tended towards religious skepticism.

Brugha was often rather more scrupulous morally and ethically than many of his colleagues (as Collins could be, too). On the other hand, writing about his involvement in a plot to assassinate British cabinet members during the Conscription crisis in 1918, the authors say this episode “revealed Brugha’s tendency to lack judgement about the timing and consequences of particular actions.”

Similarly with regard to the Treaty, they add, “Brugha’s monolithic commitment to a republic blinded him to the magnitude of the Irish achievement in negotiating terms of settlement with the British government. Indeed, the agreement of a truce in July 1921 and the opening of negotiations all but guaranteed that compromise of some sort was inevitable and suggests an element of self-deception on Brugha’s part.”

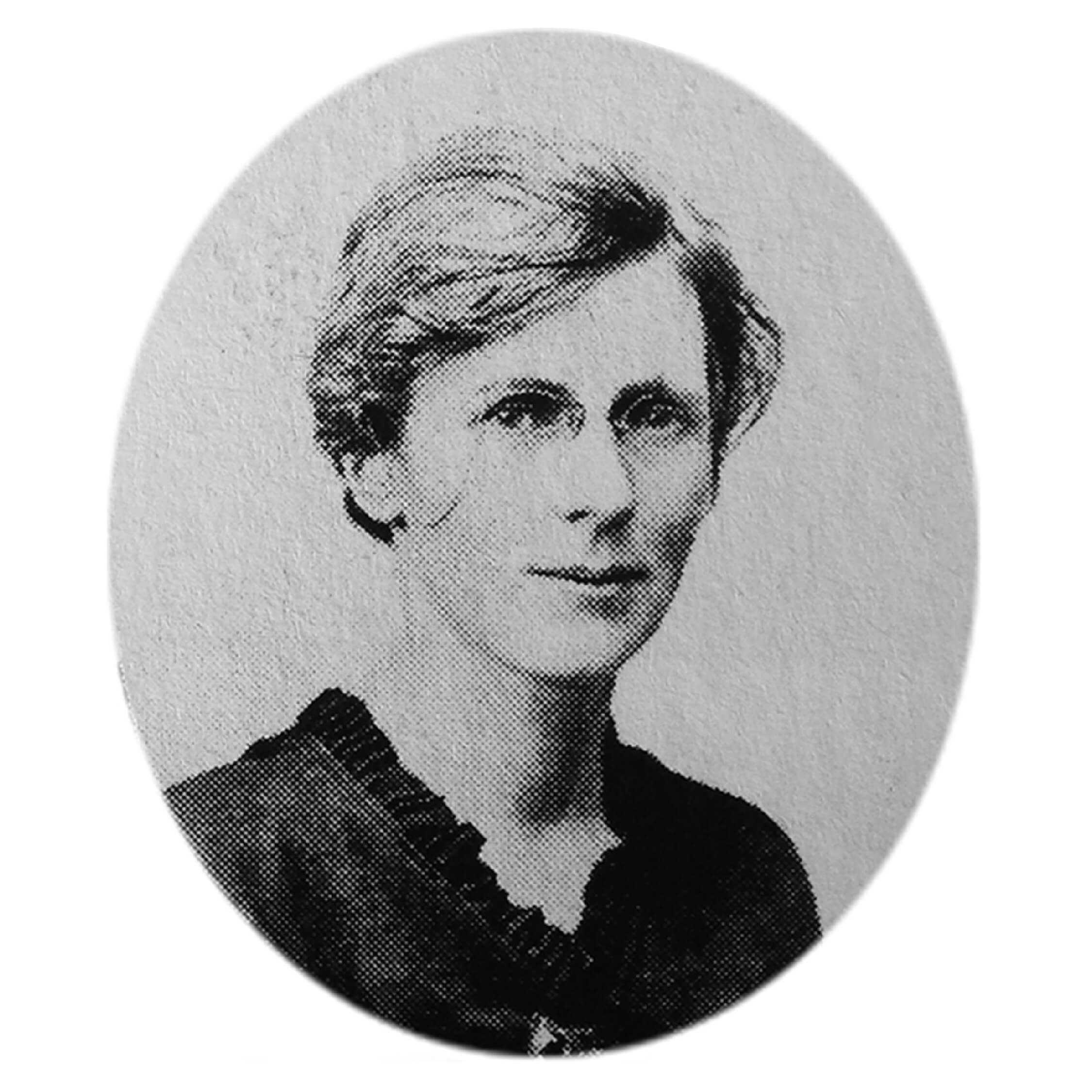

In the August 1923 general election, de Valera commended Caitlín Brugha as the “faithful companion and confidante of Cathal in his work, the partner in his sacrifice, [who] can be no less true than he was.”

She would have no truck, however, with Fianna Fáil, when it was formed, or thereafter. O Currain and Hanley don’t speculate on what Brugha’s attitude might have been. On the basis of evidence offered here, though -- particularly his moments of flexibility and relative moderation in the run-up to the Civil War -- it’s quite likely he would have followed de Valera, whom he admired.

Additionally, the Sinn Féin leader, and his closest lieutenants, Frank Aiken and Seán Lemass, had by 1925 come to the view than an army council should not lead a political or even revolutionary movement, and Brugha would have agreed.

Caitlin, who continued as a Sinn Féin TD until it faded as an electorally viable force, bitterly attacked any official use of her dead husband’s name by his former comrades. In the mid-1930s, she supported the marginalization and eventual expulsion of Sinn Féin president Fr. Michael O’Flanagan for his collaboration on cultural projects with government institutions.

Caitlín Brugha.

Two of her six children became involved with paramilitary activity, daughter Nóinín and son Ruairí. Arresting the children of a revered martyr presented something of a problem for Fianna Fáil, not least given that the Justice Minister concerned was Gerald Boland, brother of Cathal Brugha’s admirer and fellow republican fatality in 1922 Harry Boland. In 1942, looking for Nóinín at her mother’s home, the authorities found Günther Schütz, a German agent who’d escaped from Mountjoy Prison. Senior government ministers considered charging Caitlín, but thought better of it. Ruairí’s wife, Máire MacSwiney Brugha, the daughter of Terence MacSwiney, said decades later of the episode: “I think, as usual, the Republican movement was using Mrs. Brugha.”

Caitlín had a successful business career after politics, setting up Kingston’s, which developed into one of the best-known menswear stores in Ireland. (It was located on the site of the old Hamman Hotel, where Cathal Brugha, de Valera and others reported for duty at the beginning of the Civil War.)

Ruairí left the IRA and joined Sean MacBride’s Clann na Poblactha, and would remain a member for 15 years. At age 31, he ran for the party in the 1948 general election, but was defeated. A few years after his mother’s death in 1959, he joined Fianna Fáil. Although he adhered firmly to his republican ideals, he was a political moderate, and was appointed by leader Jack Lynch as Northern Ireland spokesman when the party was in opposition in the 1970s.

Dissatisfied with the cliched and hagiographical accounts of his father’s life, Ruairí Brugha wanted to get a fuller picture and sought out people who knew him, including General Richard Mulcahy, who'd worked with him during the War of Independence and was his successor as Minister of Defense after the Treaty split. His efforts have proved enormously valuable to Ó Corráin and Hanley in their research for this fascinating and impressive portrait.

The authors leave the last tribute to the co-founder of the Gaelic League and the Irish Volunteers and member of the Free State government Eoin MacNeill, who said in 1922, “Cathal Brugha, in all that I ever knew of him, was an honest, honorable, brave and unselfish man. I have no doubt at all that he was a man who acknowledged the law in his conscience to be supreme in everything, and who with that in mind gave his wholehearted allegiance to Ireland, setting his duty to Ireland above life and the claims and ties and affections that he found in life. What more can be said for any of us?”

Daithí Ó Corráin

Date of birth: 1977

Place of birth: Kerry

Spouse: Ailís

Children: a little boy, 5, and a little girl, 2

Residence: Dublin

Published works: “Rendering to God and Caesar: the Irish churches and the two states in Ireland, 1949-73” (Manchester UP, 2006); “The dead of the Irish Revolution” (Yale UP, 2020) [co-author Eunan O’Halpin]; “Cathal Brugha: An indomitable spirit” (Four Courts Press, 2022) [co-author Gerard Hanley]; series editor (with Mary Ann Lyons) of the landmark Four Courts Press series of county histories of the Irish Revolution. Volumes on Sligo, Tyrone, Waterford, Monaghan, Limerick, Louth, Derry, Leitrim, Kildare, Roscommon, Antrim, and Donegal have been published. All 32 counties will be covered.

What is your writing routine? Are there ideal conditions?

I would love to discover ideal writing conditions! This book was written during the least favorable circumstances during the awfulness of the Covid pandemic. Maintaining a writing routine was difficult. I wrote mostly late at night when the house was quiet, my young children were asleep, and the kitchen table was free of toys. During the height of the pandemic the wonderful librarians in Dublin City University helped enormously. I cannot thank them or the team at Four Courts Press (my publishers) enough.

What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

Three general pieces of advice have stayed with me throughout my career. The first is simply not to give up – writing is rarely easy or straightforward, and sometimes staring at a blank screen or page is part of the process. The second is Seán Ó Faoláin’s truism that the art of writing is re-writing. Lastly, write something every day, even if only a few lines because it keeps you focused and builds momentum.

Name three books that are memorable in terms of your reading pleasure.

This is such a difficult question and I’d like to list 20. But here goes: Patrick Kavanagh, “Tarry Flynn”; William Styron, “Sophie’s Choice”; W. Somerset Maugham, “Of Human Bondage.”

What book are you currently reading?

“All the Light We Cannot See” by Anthony Doerr and it is unputdownable.

Is there a book you wish you had written?

As a historian of 20th-century Ireland, I remain in awe of Michael Laffan, “The resurrection of Ireland: the Sinn Féin party, 1916-1923,” and Charles Townshend, “Easter 1916: the Irish rebellion.”

Name a book that you were pleasantly surprised by.

“The Good Soldier” by Ford Maddox Ford.