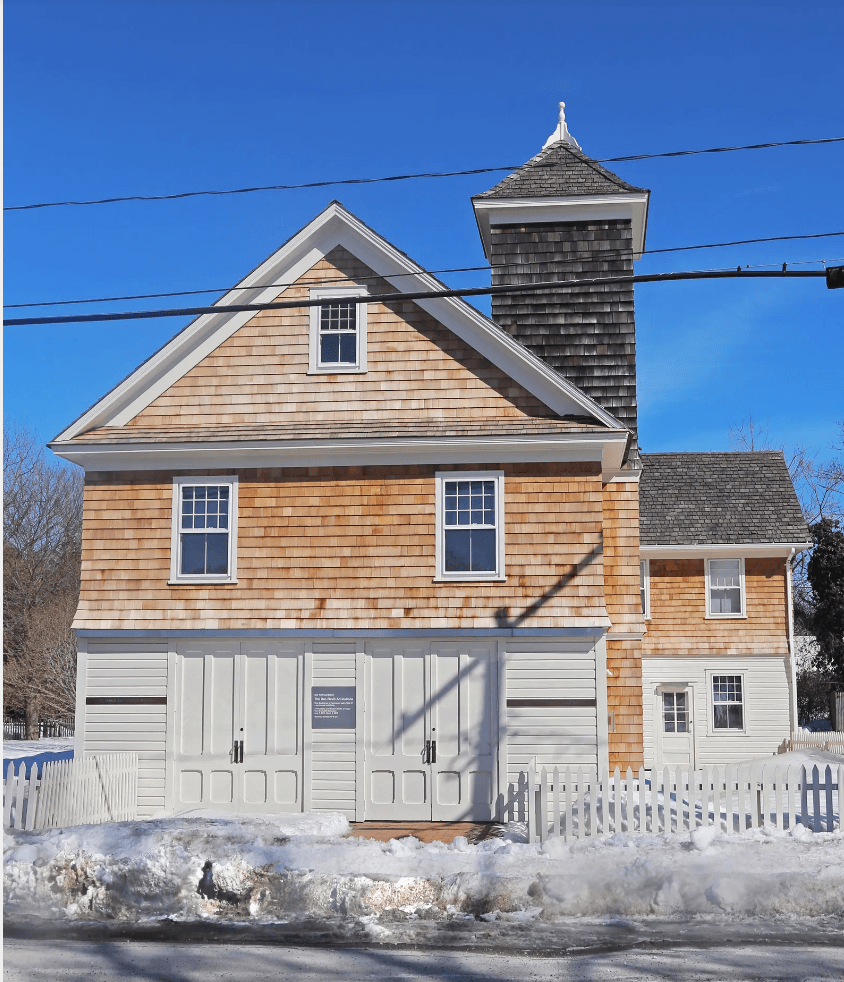

In their rush to reach the sanctuary of the Hamptons, thousands of people ignore the Dia Bridgehampton Art Museum, an unpretentious shingled wood frame building, whose second floor contains nine works of Dan Flavin, an artistic genius and amongst the most important visual artists of the 20th century. Flavin, who lived nearby in the East Hampton hamlet of Wainscott, renovated the building’s interior and transformed it into a museum that would house his world-renowned light installations.

A rotund figure whose cheerful, cherubic looks belied his brilliant and caustic wit; Flavin belonged to a generation of artists who redefined American art. He was perhaps the first artist to use electric light to create works of art and he became celebrated for turning incandescent light into an innate artistic material, like paint or clay. Writing of his work in the Observer in 2006, art critic Laura Cumming gushed, "You wonder how it is possible that so much pleasure could emit from such a dismal source: the cold fluorescent tubes of strip lighting."

Flavin spent many years working menial jobs before he had an artistic epiphany that would transform his life. Dan Flavin Jr. was born in New York City on April 1, 1933. His parents apparently did not encourage their son's early demonstrations of artistic interest. A former altar boy, Flavin recalled being ''curiously fond of the solemn high funeral Mass, which was so consummately rich in candlelight, music, chant, vestments, processions, and incense.” The future artist studied for the priesthood at the Immaculate Conception Preparatory Seminary in Brooklyn between 1947 and 1952 before leaving to join his twin brother, David John Flavin, in the United States Air Force.

Dan Flavin.

He returned to New York after serving in Korea and briefly attended the Hans Hoffman School of Fine Arts and studied art under Albert Urban. He then went on to Columbia University where he studied painting and drawing. Having little success as an artist, he worked in the mailroom of the Guggenheim Museum and as an elevator operator at the Modern Museum of Art before a humble light fixture would change his life and create a new kind of art.

In the spring 1963, Flavin took a standard 8-foot-long yellow fluorescent lighting fixture and mounted it to the wall of his studio at a 45-degree angle, the lowest corner of the unit's housing just touching the floor. He plugged it in and turned it on and it cast a golden light across the wall and into the room. Flavin grasped, as he later wrote, that ''the actual space of a room could be disrupted and played with by careful, thorough composition of the illuminating equipment.'' Flavin grew immediately intrigued, writing of this “buoyant and insistent image which, through brilliance, somewhat betrayed its physical presence with approximate invisibility.” He realized that this humble lighting fixture could serve as a powerful artistic medium.

Before that fateful day, he had used light fittings, mounting small incandescent bulbs and short strip lights to a number of plain, painted boxy structures, which he called icons. They were beautifully crafted, and took him a long time to make. Mounting the strip light on the wall, however, took almost no time or effort at all. From May 1963 until his death on Nov. 29, 1996, Flavin worked exclusively with standard fluorescent lighting units and tubes. Remaining faithful to his discovery, he always worked only with tubes that were commercially available. His color choices were limited to the standard spectrum of colored tubes, as well as the full range of white lighting - warm white and soft white, daylight and cool white. Sometimes he employed the "black light" of ultraviolet tubing. They remained Flavin’s sole artistic material for the next 33 years.

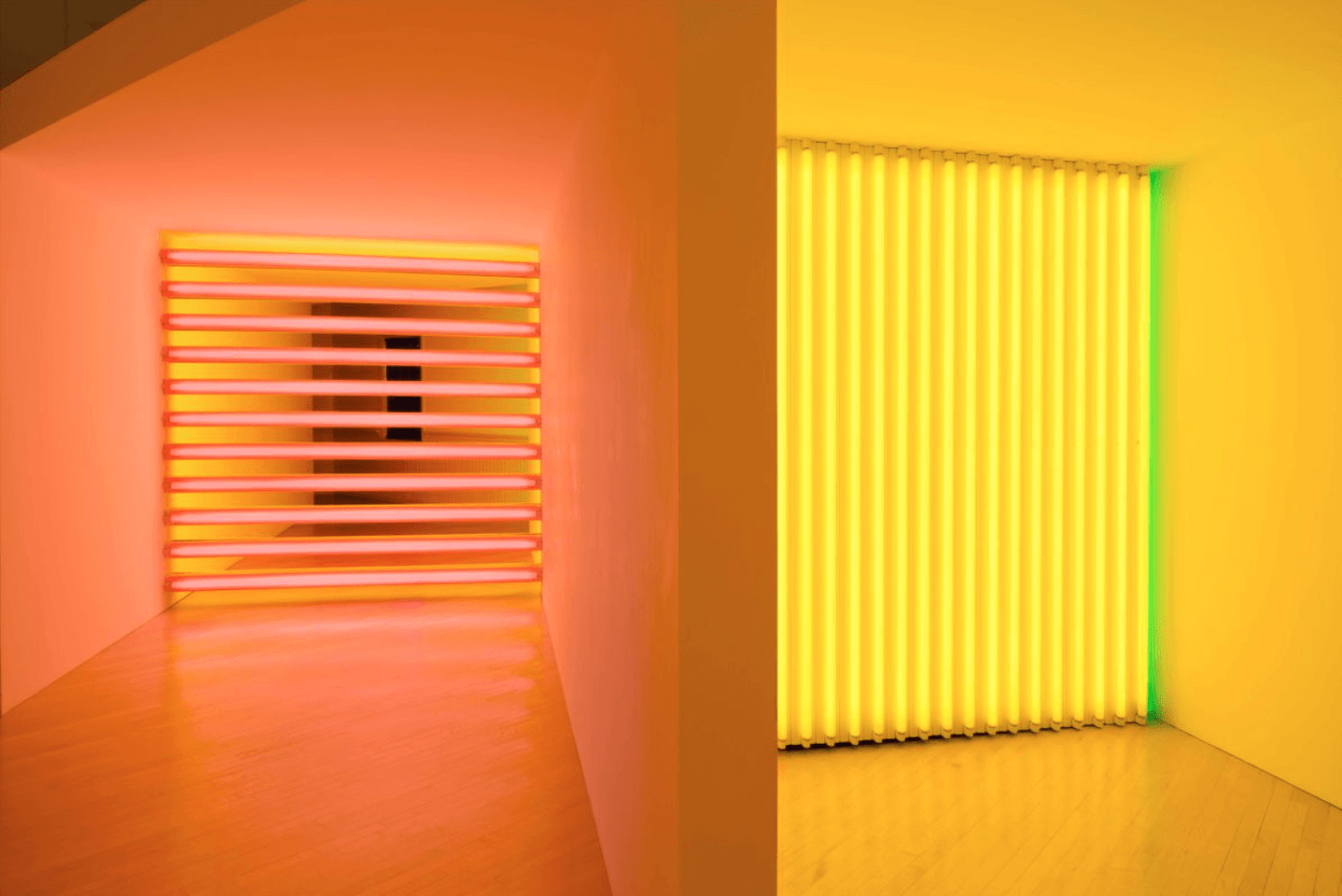

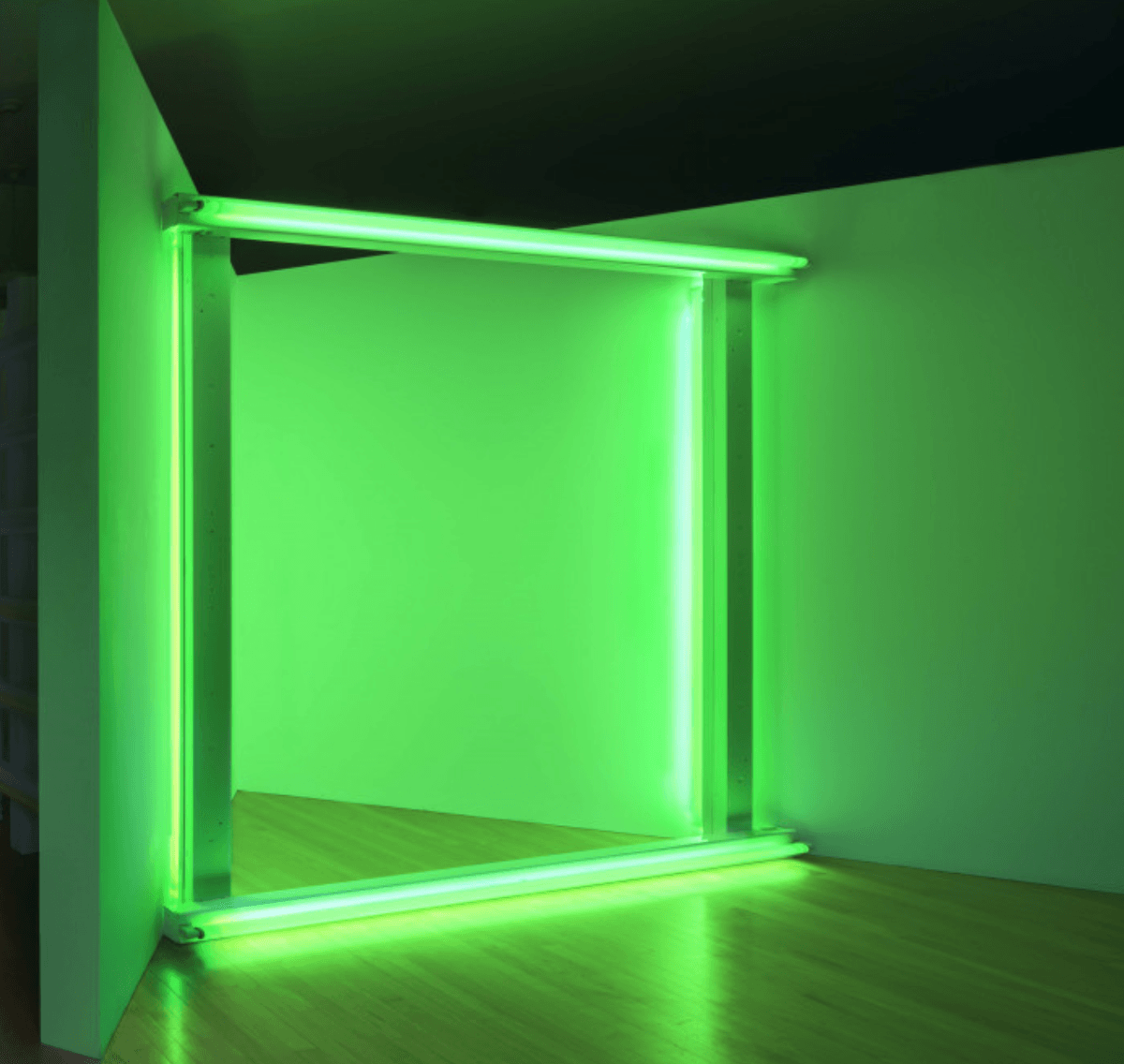

Flavin would use fluorescent tubes to transform art, moving it away from cubism toward a new focus on space itself. He began using the tubes on their own, placing them in fence-like barriers across rooms or doorways, in vertical arrangements along walls and in various crisscrossing or frame like constructions that spanned corners. The light from the tubes created an ecstatic beauty that was simultaneously architecture and painting. This beauty came from a combination of the tubes' intense lines of color, the softer glow of their diffuse, spreading light and the geometric arrangements of the tubes' metal pans. Flavin displayed a genius for configuring lights. His lighting can be pictorial, conceptual, colorist or graphic. They can dissolve or divide space, soften concrete, become their own architecture of walls, doors, and windows. An ultra-bright glowing fence stretching right across the entrance gallery transforms a dour old space into one that undulates while changing all its hues and shadows.

Flavin enjoyed what he considered the paradox of the commonplace: the everyday industrial hardware itself, and the incidental, uncontrollable spread of the light. He liked the shadows cast by the housings against the wall, the mixing and reflections and variety of effects the light performed as it bounced off walls, as the colors mingled, as it played games with the rods and cones of the viewer's eyes.

A difficult and contrary man as well as a complicated artist, he preferred to call exhibitions of his work "expositions", and disliked the word "installation. By 1968, Flavin had developed his sculptures into room-size environments of light. That same year, Flavin filled an entire gallery with ultraviolet light at Documenta 4 in Kassel, Germany. Soon, museums around the United States and all over Europe began staging his creations. Major retrospectives of his work include the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (1969), St. Louis Art Museum (1973), Kunsthalle Basel (1975), and Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1989).

He also executed many commissions for public work, including the lighting of several tracks at Grand Central Terminal in New York in 1976. Dia Bridgehampton, opened in 1983 as the Dan Flavin Art Institute. In 1992, the Guggenheim showcased his site-specific installation, In 1992, he filled the rotunda with multicolored light, taking full advantage of the openness of the Frank Lloyd Wright design. Additional sites for Flavin’s architectural “interventions” include the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, Chianti Foundation in Marfa, Texas, and the church of Santa Maria Annunziata in Chiesa Rossa in Milan, all in 1996.

Flavin passed away prematurely from diabetes. He helped establish a tradition that continues until now, manifesting itself in various forms of installation and environmental art. Art lovers from around the world still make their way to Dia Bridgehampton to gaze in wonder at the creations of a man who transformed hardware into fine art.