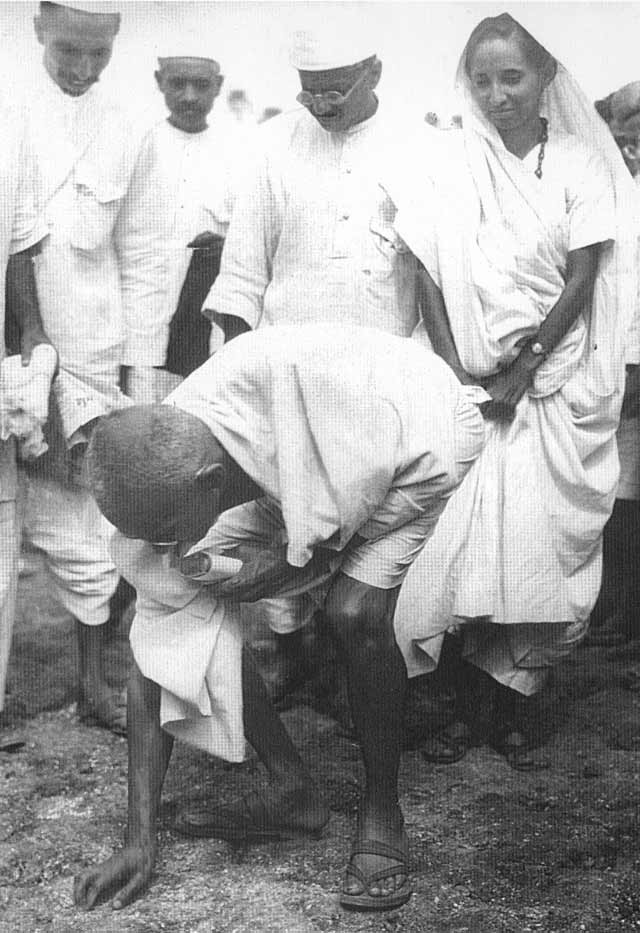

Mahatma Gandhi was a Hindu, and he was a nationalist. It would’ve been wrong, however, to describe him as a Hindu nationalist. Indeed, that was the label given to the extremist who assassinated the leader in 1948.

Its U.S. equivalent, Christian nationalism/nationalist, has similarly been identified with extremism, but these days is being embraced by high-profile right-wingers. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene is one. “I am being attacked by the godless left because I said I’m a proud Christian nationalist,” she tweeted recently.

Americans generally, though, have tended to be somewhat uncomfortable with the identification of a particular religion or denomination with the nation.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene.

The County Tyrone-born Archbishop John Hughes, the first head of the Catholic Church in New York, said "It is... out of place, and altogether untrue, to assert or assume that this is a Protestant country or a Catholic country. It is neither. It is a land of religious freedom and equality.”

Of course, cynics might say that Dagger John would have taken a different stance if Catholics were the majority. The bishops in independent Ireland in the next century really liked the idea of Catholicism being the state religion, just as it was in Spain under General Franco, whom they enthusiastically backed from afar.

They had to be content with Eamon De Valera’s Constitution of 1937, which recognized the “special position” of the Catholic Church. In Dev’s neat solution all religions were created equal, but one religion was more equal than the others.

America has tended to insist more than Europe on the separation of church and state as a matter of principle and agreement. Lately, however, this has not been the case, especially on the more conservative side of the aisle. Rep. Taylor Greene’s colleague Rep. Lauren Boebert said she’s “tired of this junk about the separation of church and state.”

Given that she has spoken of the possibility of mandatory “biblical citizenship training,” and has claimed “the church is supposed to direct the government,” Molly Olmstead predicted in Slate in recent days that it can’t be too long before Boebert explicitly labels herself a Christian nationalist, and that some others would likely follow her.

Olmstead’s piece reported that what was once taboo is now acceptable in certain circles. In the aftermath of Jan. 6, 2022, Al Mohler, the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, called Christian nationalism “idolatrous” and, Olmstead said, “pushed back on the idea that evangelical Christianity was linked to what had happened at the Capitol.”

He said in mid-January 2021, “Nationalism is always a clear and present danger” and linking “American evangelical Christianity” to that was an “accusation.”

By the summer of 2022, Mohler had done something of a U-turn. Olmstead summarized the change, “Speaking on his podcast on June 15, the theologian said: ‘We have the left routinely speaking of me and of others as Christian nationalists, as if we’re supposed to be running from that.’ He added: ‘I’m not about to run from that.’”

But what is Christian nationalism? The Slate writer said, “Christian nationalism is an academic term that encompasses different degrees of intensity. It includes more harmless, everyday God-and-country white evangelicals who believe politicians and courts should eliminate barriers separating church and state—perhaps by allowing for prayer in schools or other public spaces—as well as those with a ‘dominionist’ perspective, compelled to bring the nation’s institutions under control of people who will enforce God’s law.

“It also includes violent extremists willing to tear down democratic processes to bring about their vision of a white Christian nation,” she added. “And while the vast majority of people who could be categorized as Christian nationalists fall into the first two camps, experts worry that the idea of a self-identified label could bring different kinds of Christian nationalists more closely together.”

Olmstead consulted several experts who’ve been following the trend, but one in particular rang some alarm bells and is among those who employ the term “Christo-fascist” to cover certain categories of Christian nationalist.

Olmstead writes, “Phil Gorski, a Yale professor who studies white Christian nationalism, said he thought ‘Christo-fascism’ could apply both to the white nationalist groups that have begun strategically using Christian language as a cover to make their racist aims more palatable, as well as to the extreme Christian nationalists who openly embrace the idea of using violence to achieve their ends.

“‘That’s the most worrisome development I see,’ Gorski said. ‘More overlap in some cases with militia groups, more of this gun fetishism.’

“Right now, there’s some debate as to whether ‘Christo-fascism’ more accurately describes the danger posed by this increasingly emboldened segment of the Christian right—or if, conversely, it lets self-identifying Christian nationalists (and other evangelical Christians) off the hook for tacitly supporting extremism.”

The Olmstead piece ended with “‘A hallmark of fascism is this idea of regeneration through violence,’ Gorski said. ‘And that’s something they’re always talking around the edges of.’”