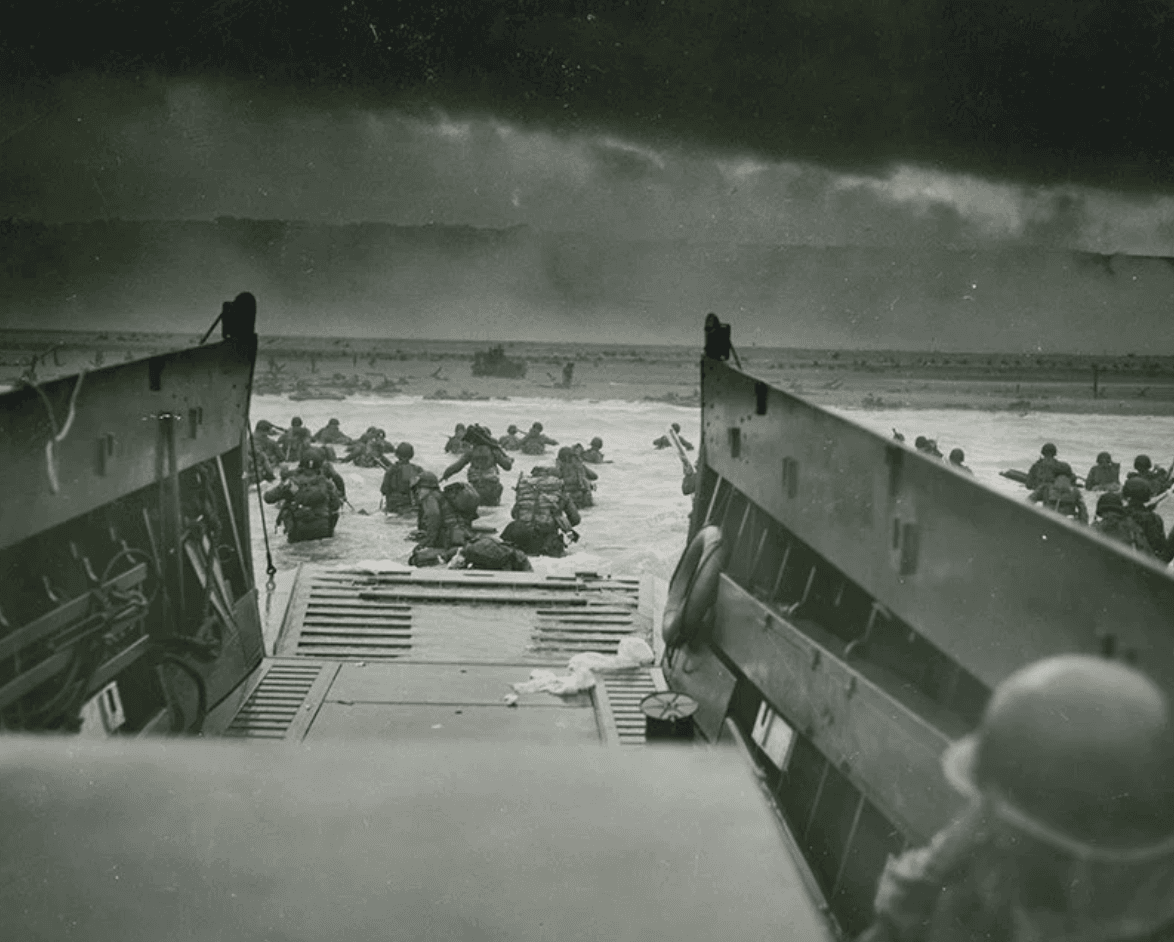

When recalling the great American heroes of the Second World War, few people mention the name Andrew Jackson Higgins, yet without his “Higgins Boat,” the LCVP he designed, America might never have won the war. General Dwight Eisenhower once said, "Andrew Higgins ... is the man who won the war for us. ... If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs [the landing craft, vehicle, personnel], we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different." Even Adolph Hitler recognized Higgins’s achievement in ship production, mockingly calling him the "New Noah."

Few people who knew Higgins in his youth could have predicted that Higgins would become a hero. Born on Aug. 28, 1886 in Columbus, Neb., Andrew was the youngest child of John Higgins and Annie Long (O'Connor) Higgins. His father, a Chicago attorney, prominent Democratic Party member and newspaper reporter, moved to Nebraska to serve as a local judge; tragedy, however, struck the family when Andrew was only 7 when his father was killed after a fall in an accident, leaving his large family in poverty.

Higgins’s mother moved the family to Omaha where Andrew grew up. Forced by age 9 to become an entrepreneur, Andrew started a lawn-cutting service, while also working several newspaper routes. As a boy, he grew fascinated by the Missouri River, whose shallows, snags and driftwood made navigation extremely dangerous for standard ships. Intrigued by the complexities of designing a boat especially for the Missouri, Higgins designed his first shallow-draft boat at age 12 in the family basement.

Later in life he reflected on his boyhood fascination with the river, “If it had not been for the Missouri River at Omaha there would have been no Higgins Industries of New Orleans turning out ships, planes, engines, guns and what have you for the army and navy… Everything else came from that.”

Though Higgins had a bright mind, he failed to graduate from high School. Considered a troublemaker by some, Andrew was expelled from the prestigious Jesuit School Creighton Prep for brawling, and in 1906, not yet 21 years old, he left Nebraska.

Higgins moved south to pursue a career in the lumber and boat business. He married and he and his wife Angele would have six children. Settling in on the Gulf Coast in Mobile, Ala., Higgins hoped to gain experience there in boat building. Working at a variety of jobs in the lumber, shipping and boat building industries, Higgins dreamed someday of starting his own company. He soon began his own businesses, but he was twice wiped out by hurricanes.

Higgins, however, never gave up on his dream. He became manager of a German-owned lumber-importing firm in New Orleans. In 1922, he formed his own firm, the Higgins Lumber and Export Co., importing hardwood from Asia, South America and Africa, while also exporting bald Cypress and pine. His firm acquired a fleet of sailing ships, one of the largest commercials then under American registry. As part of the business, he established a shipyard, which built and repaired cargo ships, tugs and barges. To help him master shipbuilding, he took correspondence courses in naval design through the National University of Sciences in Chicago.

A gifted, visionary shipbuilder, in 1926, he designed his revolutionary Eureka, a shallow-draft ship, especially suited for the bayous and rivers of the Gulf Coast, where oil drillers, trappers and loggers faced debris and submerged obstacles that could damage craft with conventional propellers. His Eureka boat, with a propeller recessed into a semi-tunnel in the hull and "spoonbill" that allowed it to be run onto riverbanks and then to back off with ease, soon became a commercial success. A born tinkerer whose motto was “The hell I can’t,” within a decade, Higgins had improved his design to attain high speed in shallow water and turn nearly in its own length of water.

By 1937, Higgins was producing his Eurekas with a staff of 50 or so workers in a little New Orleans boatyard. The Marine Corps , frustrated by the Navy’s inability to design a suitable landing craft, became interested in Higgins’s boat, and decided to test it against government-built landing crafts. His boat outperformed the government’s model.

Higgins started making landing craft for the Navy just as World War II began. Military planners, however, demanded that he modify his design to include an opening ramp in the bow, and he went back to the drawing board. Within a month, tests of his new ramp-bow Eureka boat showed that it was ideal for amphibious landings. At first, he built a 30-footer, the Landing Craft Personnel (LCP), based on government specifications but he insisted a larger boat would be even better. The Navy finally agreed, and Higgins developed a 36-foot version, the Landing Craft Personnel Large (LCPL), that would become known as “ “the boat that won World War II.” His ship carried up to 36 men from transport ships to the beaches and also could haul a Jeep, small truck or other equipment with fewer troops. Higgins also designed an ingenious protected propeller system that enabled the boats to maneuver in only 10 inches of water.

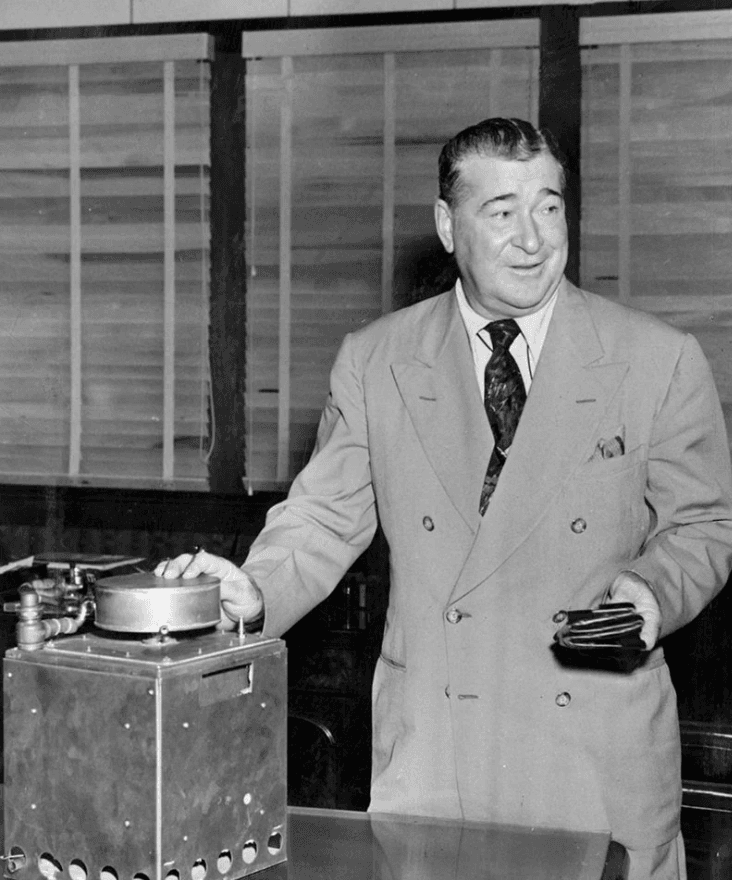

A perfectionist obsessed with good workmanship, Higgins was also uniquely able to rapidly expand his shipyard production to produce not only Higgins Boats, but also other kinds of small naval craft and even aircraft—whatever the war effort needed. By the end of the war his firm became one of the biggest industries in the world, with upwards of eighty thousand workers and government contracts worth nearly $350 million.

Finding qualified labor was hard during the war and Higgins, believing in a diversified workforce for his plants, hired all races and both genders, taboo in the segregated south. Everyone who had the same job was paid the same wage. and together they set home-front production records. Winning the Army-Navy “E”—the government’s highest award for a company—was commonplace for Higgins Industries.

Andrew Jackson Higgins.

His boats first saw combat in Africa in 1942. By 1943, 12,964 American ships, an amazing 93 percent of all U.S. Navy vessels, were designed by Andrew Higgins and his company. Higgins boats played vital roles at D-Day, Iwo Jima and dozens of other amphibious assaults. His company produced over 20,000 boats during the war, but Higgins was even more amazing than his company. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s adviser Raymond Moley wrote in Newsweek in 1943. “But it is Higgins himself who takes your breath away as much as his remarkable products and his fantastic ability to multiply his products at headlong speed. Higgins is an authentic master builder, with the kind of will power, brains, drive and daring that characterized the American empire builders of an earlier generation.”

Recognized as an innovative genius, Higgins held over 30 patents, mostly related to amphibious landing craft and vehicles. Higgins died in 1952 without receiving all the honors he was due. Today, however, Americans are finally starting to realize his immense contributions to Allied victory. Higgins biographer Jerry Strahan said, “ Without Higgins’s uniquely designed craft, there could not have been a mass landing of troops and matériel on European shores or the beaches of the Pacific islands, at least not without a tremendously higher rate of Allied casualties.”

In 1987, the United States Navy named a ship after Higgins and in 2000, a 7-block section of Howard Avenue in the Warehouse District of New Orleans was renamed "Andrew Higgins Street." Today, his statue stands at Utah Beach in Normandy, where victory was achieved, and thousands of lives were saved by this ingenious Irish American.