Though few people today remember his name, millions of people around the world know Thomas Crawford’s most celebrated creation, his massive statue “Freedom,” which stands atop the dome of the American Capitol building in Washington D.C., arguably the most famous statue ever created by an American. They also know his iconic frieze that graces the capitol. In the pre-Civil War period, no sculptor contributed more than Crawford to the development of American sculpture, even allowing for his early death.

Though many biographies say that the sculptor was born in New York City in 1814, other sources contradict this claim, stating Crawford was actually born in Donegal, and only arrived in the nation’s largest city as a 7-year-old. Two questions arise? Did Crawford hide his Irish birth and if so, why would he conceal the land of his birth?

Crawford was the son of Donegal Protestants, Mary Gibson and Aaron Crawford, who, it’s claimed, later emigrated to the United States with their son. In his 1879 work “Ballyshannon: Its History and Antiquities,” author Hugh Allingham said that that town, not New York City, was Crawford’s true birthplace. The author cited as evidence statements by the sculptor’s Donegal relatives attesting to his Irish birth and also a published admission by Crawford’s mother, the former Mary Gibson.

The New York that Crawford grew up in during the 1820s was far different than the cosmopolitan, multi-religious and muti-ethnic city it is today. During the sculptor’s youth New York had only about 5,000 foreign born residents out of a population of 123,000. A contemporary of the infamous anti-immigrant brute Bill “The Butcher” Poole immortalized in the film “Gangs of New York” by Daniel Day Lewis, Crawford might have wanted to conceal his Irish birth to be accepted by his fellow New Yorkers.

Sources reveal little about his birth and early years, but we do know that even as a young child Crawford showed an obsession with art that would remain a defining trait for the rest of his relatively short life. From age 9 to 14, he was so preoccupied with sketching and making watercolors that his schoolwork suffered. When it came time to choose a career, he refused to enter more conventional jobs and instead opted to become a woodcarver. He soon mastered all the subtleties of woodcarving and then moved on to marble. He found a job with one of the few American stonecutting firms, the New York firm of Frazee and Launitz. Crawford apprenticed under Robert Launitz in New York, a Latvian-born sculptor who had trained in Rome under Bertel Thorwaldsen, a Danish master sculptor and an artist who would later have a massive influence upon Crawford. Both John Frazee and Robert Launitz fostered Crawford’s natural ability and inspired the classical sculpting style he would later become known for.

Today, New York is one of the world’s art capitals, so it is hard for present-day New Yorkers to imagine how artistically stifling New York City was for an aspiring sculptor in the days of Crawford’s youth. In his mid-teens, Crawford began to take art lessons at the American Academy of Fine Arts on Barclay Street in Manhattan, but the creative environment was extremely limited. There were no nudes to study anatomy from. The city had very few sculptures and those deemed prurient were kept under lock and key. There were not even photographs of the great works of antiquity or the Renaissance. It was almost impossible for a sculptor to transfer his clay creations to marble.

Crawford, though, was both fearless and extremely ambitious. Hoping to escape the severe limitations of New York City’s artistic milieu, the young apprentice decided to travel to the best place in the world to study sculpture, the Eternal City, Rome. Traveling abroad was a highly unusual move. Could Crawford’s decision to leave America have been influenced by his parents who also chose to leave the land of their birth for better opportunities?

Crawford left New York for Rome in 1835 at age 21 with a letter of introduction from Launitz to his mentor in Rome, Bertel Thorwaldsen. His trip to Rome was risky, even dangerous. He had very little formal training as a stonecutter. He knew no one in Rome, had little money and spoke no Italian, but Crawford always had great self-confidence and self-assurance.

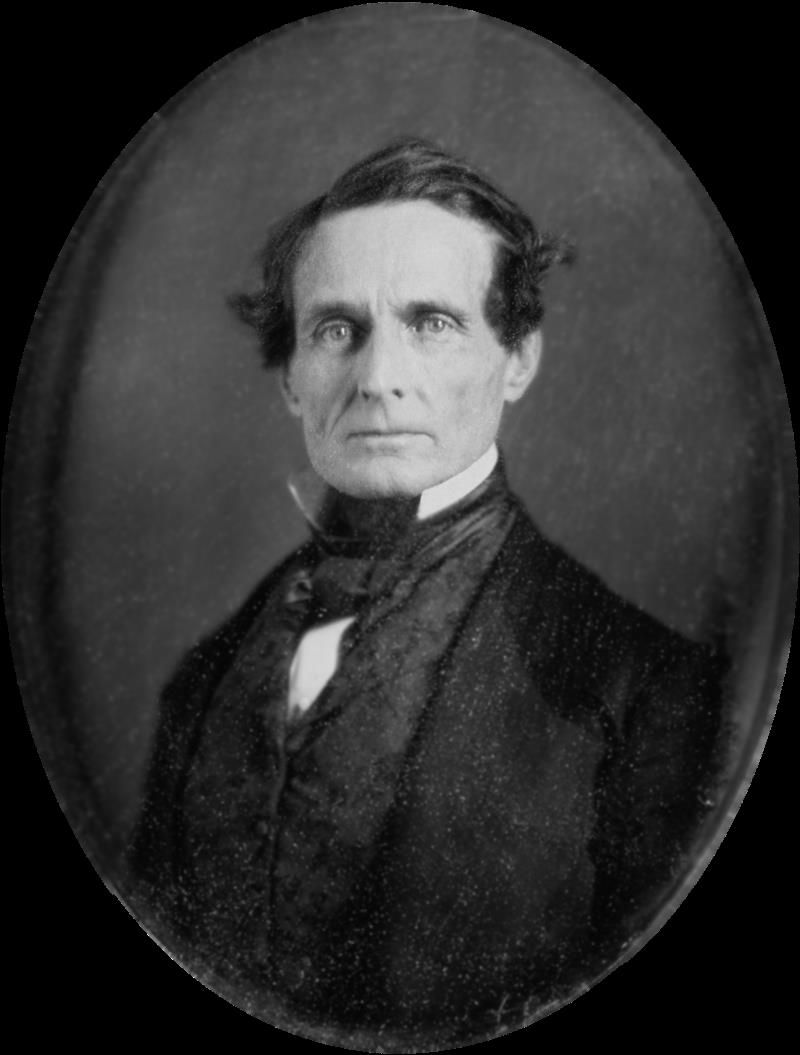

Thomas Crawford.

Thorwaldsen accepted him into his studio and began to train him. The Danish master also became a friend and mentor. Under his guidance, Crawford devoted himself to the study both of the antique and of living models Throughout his career, Crawford’s sculptures were heavily influenced by Thorwaldsen’s neoclassical sculptural techniques.

Though he had found work and a teacher, Crawford lived the life of the starving artist. The sums he received for his creations barely sufficed to pay his bills and purchase necessary materials; but he was glad to work for any pay at all, believing that he could only reach excellence by incessant labor. Crawford even opened a studio in Rome and is credited with being the first American sculptor to settle there. Word of his unique talents spread and his studio quickly became a magnet for Americans visiting Rome.

America had no great sculptor at this time and important Americans championed him as the first. Harvard-trained lawyer and future U.S. Senator Charles Sumner became an advocate for Crawford. They bought his work, in part, because they wanted to support an American artist. Had Crawford revealed his Irish birth he probably would have lost many of these early commissions that sustained him.

Crawford married into one of the richest and most prestigious New York families when he wed Louisa Ward, the stunning daughter of a well-to-do Wall Street lawyer. Her sister Julia was a poet and would later pen the famous verse “The Battle Hymn of The Republic.” They met in 1844 and quickly fell in love, much to the chagrin of her family who were not pleased that she was marrying a man of such limited financial means. Crawford would not have been eager to reveal his humble, immigrant background to his powerful in-laws.

In 1839, Crawford created a piece that would set him on the road to recognition and well-paid commissions. Entitled “Orpheus,” it became Crawford’s first major neoclassical conception. A full-length ideal work, it received rave reviews. Sumner, who saw it in Rome, was so struck with its beauty that on his return to Boston he solicited subscriptions to raise money for Crawford to copy it in marble. Sumner then acquired it for the Boston Athenaeum.

So successful was “Orpheus” in its combination of lofty theme and purity of revived classical aesthetic that Crawford was honored by a small sculpture exhibition at the Athenaeum, the first one-man exhibition of the work of an American sculptor.

When visiting the United States in 1849, Crawford read a newspaper article about a competition sponsored by the Virginia General Assembly for an equestrian statue of George Washington surrounded by other prominent figures from Virginia history. He had been dreaming of such a statue for years. He quickly prepared his model, which was unanimously chosen by the selection committee. He wrote to his wife after receiving word that he had won the commission, “The sun shines at last, dear Lou! I have beat them all, and the monument is mine. I have at last been permitted to realize all my artistic dreams and have received a work that any artist might be proud to have the honor of executing.”

He immediately returned to Rome and designed a star of five rays, each one of these to include a statue of historic Virginians, including Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson. At the center of the star rose an imposing equestrian statue of George Washington. His creation was hailed as one of the finest American sculptures ever executed.

In 1853, Crawford, now a famous sculptor, received his greatest commissions, the bronze doors to the United States Senate and House of Representatives, the frieze adorning the capitol building and the massive statue that would stand atop the capitol dome. The engineer in charge of the project wanted classical, symbolic sculptures for the pediments similar to the Parthenon in Athens and Crawford designed such a marble classical pediment, depicting scenes from early American history, called “The Progress of Civilization.” The three-dimensional figures he created show an amazing attention to detail. The two huge bronze doors he created are reminiscent of the doors of the Florence Baptistry created by Renaissance master Lorenzo Ghiberti.

Crawford’s greatest design, “Freedom” was also his most controversial. A massive bronze standing figure almost 20 feet tall and weighing approximately 15,000 pounds, it stands atop the Capitol, but it also generated fierce protests by slave owners. Originally, the plans for the figure atop the dome called for a statue representing the goddess of liberty, but Crawford instead proposed an allegorical figure of “Freedom Triumphant in War and Peace.”

Crawford’s design was accepted in 1854 and during that same year he sculpted the plaster model for the statue in his Roman studio. U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who a few years later would become President of the Confederacy, headed the Capitol building project and held a veto over the statue’s form. According to David Hackett Fischer in his book “Liberty and Freedom,” Crawford’s statue was quite close to Davis’s ideas, except above the crown where New York abolitionist Crawford had added a liberty cap, the old Roman symbol of an emancipated slave. This made the slave-owning Davis explode with rage, and he angrily demanded its removal. Crawford instead substituted a military helmet, with an American eagle head and crest of feathers. Even Davis had to admit the unique beauty of Crawford’s elegant design. No other artist had done as much to grace the Capitol, but tragically Crawford would not live to see his designs realized.

Jefferson Davis in a daguerreotype from 1853, when he was U.S. Secretary of War.

In 1856, at the height of his artistic powers, and fame, Crawford’s sight began to deteriorate rapidly. He sought medical treatment in Paris, and physicians discovered cancer of the eye and cancer of the brain. Desperate, Crawford agreed to undergo an untested medical treatment that destroyed the eye and orbital contents. He died five months later in London on October 10, 1857, at age 44, never seeing any of his Capitol sculptures mounted. His body was returned to the United States, and buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. His statues in Richmond, which he also never saw, were also unveiled after his death.

Though his life was cut short, Crawford left America a huge artistic legacy. He spent less than 20 years in active studio labor, yet in that short span he designed and saw into completion more than 60 works, many of them gigantic. He left more than 60 other works in clay and plaster. If he had lived his three score and 10, he might have become an American Donatello or Thorwaldsen. He might have also revealed that the great American sculptor was actually an immigrant from Donegal, but perhaps he brought this secret to his grave.