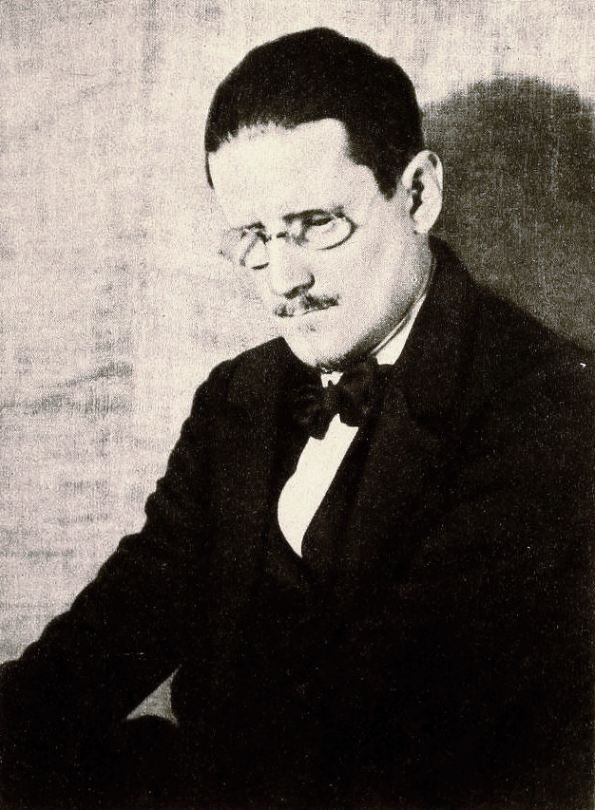

In the first weeks of 2022, some leading publications were on top of the centennial of James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” which was published on Feb. 2, 1922.

“Love, soppy as it may seem, is the novel’s great subject,” author and academic Merve Emre commented in an admiring New Yorker essay. Meanwhile, novelist Anne Enright wrote in the New York Review of Books, “Joyce has been in our brains, playing in the place where meaning is made, and this can feel disturbing or delightful.”

Many fans, though, have been waiting for Bloomsday 2022 to celebrate 100 years of “Ulysses.” And so as June 16 approached we asked nine people to describe their personal relationship to the novel.

DELIGHTFUL FEVER DREAM / RACHAEL GILKEY

2002. I first approached it with my hand held. A classroom. Guidance, dissection, discussion. A chapter a week. I loved it, but I lost something.

2003. In Galway, I sidled by Nora Barnacle’s childhood home. In Paris, I stepped amongst the shelves of Shakespeare and Company and saluted Sylvia Beach.

2007. I tackled it again, but this time submersion. Between Christmas and New Year’s I read a hard cover copy printed the year I was born. And it was a delightful fever dream. Yes I skipped the parts that bogged me down, yes, I did, yes.

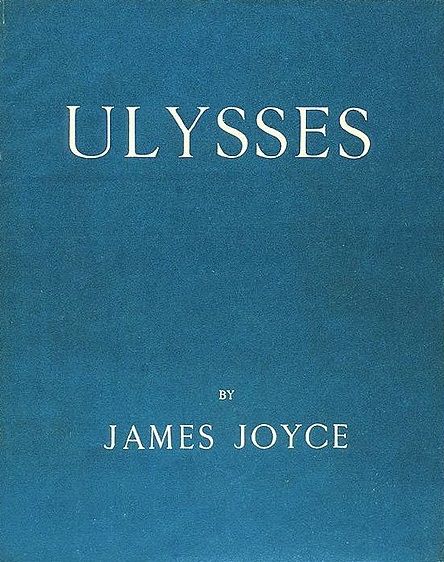

2008. Bought a copy with the iconic blue cover. Why do I own three copies? One to mark up, one to admire, one to lend out.

2009-2022. Bloomsday on Broadway! Hearing the words spoken aloud and gaining a new access point. Begins a new tradition that grows to include other Bloomsday celebrations in New York, ones I get to collaborate on and ones I get to just enjoy, that begin in the early morning and end at midnight, traveling a figurative map of Dublin overlaid on my own beloved City. I read “Ulysses” again and again, in full, in segments, to edit texts for Bloomsday celebrations, or just to dig deeper. It’s possible I know it, better, now. But it’s also possible to not try to know it. And still love it.

Rachael Gilkey is Irish Arts Center’s director of programming and education.

Rachael Gilkey [Photo: Rich Gilligan]

TOO UNSENSE TO BE OBSEEN / PETER QUINN

all in all it's among the great iron knees of the litterature of the modern rage that the singletoast homohymn to the common man should get booed and booted for elitist uninteeligiblty, a rap first rapped by Gotham mouthpiece the Mighty Quinn when he told magistraight’s court JJ's tome was too unsense to be obseen, when instyd it is the most elophant put down of the fauxknee fascist hiccups of blud and sooil, a cerebralation of the liffy dignitree and densitree of the shit and shinola of the extraordinarily ordinary me(and you)anderings through sheets and streets shared by paddy jew and molly too beneath the Doublean dark and blazes’ boiling sun, musta odor of jakes and gorgonzola, thick cobblestone, tombstone, library tome, hamlette and peenellopee, where lies in state the state’s lies and praying mantestes, and prelated prelates obfuse the obvious and Gerleen insired fireworks in a man’s pants squirts the ineffable inelucability of our cumings and goings, all in all, skinny and plump, stately and unsightly, shriveled and unshrivenable, she and he, no better or liviawurst than you and me as we make our way beneath the purabella sky to day’s end and the merciful yea of bed’s warm and welcoming spread, yes.

Peter Quinn’s “Cross Bronx: A Writing Life” will be published on Sept. 6.

The 1st edition.

LAW LESSONS / JAMES RODGERS

Although I studied “Ulysses” in high school and college I did not attempt to read the entire novel until well into adulthood. I read the first 50 pages. Then I put it on a bookshelf in our apartment hallway. Every day for 10 years I passed that book and reminded myself to read it. Eventually, the sense of failure became too strong and I picked it up again. When I finished the novel I wrote, “Finished reading Ulysses on April 2, 2005 at 9:56 pm. Yes, I did, Yes!” And then I signed my name.

“Ulysses” has many themes, styles, and is driven by an outline from a classic. But distilled it has two strings to be followed—the story of Leopold Bloom’s day and evening where he circumnavigates Dublin meeting a montage of friends and characters as he slowly heads for home and his Molly, and then the periods of dream sequences, streams of consciousness, literary sidebars, and a plethora of metaphysical transformations that take the reader into a web of bewilderment.

The second time around I found myself using a method gained from reading thousands of law cases. In many decisions judges go off tangent departing from the main issues and pontificating with legal reasoning that seems to have no bearing on the case. Lawyers learn by the time they finish law school that the key is to keep reading as the judge will eventually return to the issues and make the decision. The off tangent portion, while often seeming incongruous, is where the judicial gems can be found. So too is how one must read “Ulysses.” Rather than attempt to figure how the second string of the story fits in it is best to just read on, absorbing and enjoying the literary genius of Joyce as he will always return to Leopold Bloom in the flesh who will, late at night, return home to 7 Eccles Street where Molly lies upstairs contemplating her life in full erotic “bloom,” rendering her thoughts and passions a singular literary masterpiece worthy of its own stand alone dramatic performance.

To writers of fiction and students of creative writing the value of “Ulysses” is immeasurable. Besides illustrating to the reader an almost unlimited array of literary styles, which are instructive on their own, writers can be released from the shackles of formalistic methods of writing and begin not to copy Joyce but to find one’s own style and own voice free of the barriers that exist in writing conventional prose. Simply put, “Ulysses” gives the writer the confidence to shoot the literary moon. So trust Joyce, who will be peering over your shoulder saying, “Yes, you can, Yes!”

James Rodgers practices maritime law in New York City and is author of the novel “Long Night’s End.”

BLOOMSDAY BLISS / AIDAN CONNOLLY

Richard Murphy, professor of English at Providence College, introduced me to Ulysses in my junior or senior year, in a dazzling and challenging modern literature course that also offered an introduction to Virginia Woolf’s “The Waves.” With Dr. Murphy’s engaged, though wholly unpretentious guiding hand, both these works were revelations to me, inspiring a passion for form-challenging narratives of all kinds, and a belief that when our emotions are engaged, we humans have an incredible capacity for adapting to new languages of art.

I’d return to “Ulysses” just a few years later when I was invited by my future friend and mentor Isaiah Sheffer to be one of the readers in Bloomsday on Broadway 2001 at Symphony Space. Isaiah was a visionary in rendering the novel — for all its esoterica and peculiarity — accessible to audiences of all stripes, through the relentless mining of laughs to be found in the text, delivered by his ever-eclectic ensemble of actors, writers, and assorted Upper West Side characters (the latter of which was clearly my primary qualification!) I was invited to be a small part of a large ensemble (including, if memory serves, everyone from Barbara Feldon to Stephen Colbert), for a segment called “What They Ate and Drank,” featuring a selection of the more consumptive segments of the novel, curated and directed by an inimitable and relentlessly delightful fellow by the name of Malachy McCourt.

Little did we know that night that in a matter of weeks the world would change so profoundly and unalterably. But for that night: laughter and bliss.

Aidan Connolly is the executive director of Irish Arts Center.

Bloomsday Breakfast, Bryant Park, 2011.

EMULATING BLOOM / GEORGE FOY

My grandfather's stately, plump, 1934 Random House edition of “Ulysses” (freshly freed from the censor's ban) came from the stairhead of my 20-year-old consciousness, bearing a bowl of linguistic lather on which notions of artistic freedom and narrative agility lay crossed; in other words, to this nascent writer, Joyce's novel became forever an exhortation to scrap rules in favor of getting across the guts and steam of whatever character drives fiction, and I suppose it was that sense of liberty powering my excitement when I first dipped into the peregrinations of Leopold; more so when, celebrating Bloomsday in Dublin years later, I emulated Bloom by getting royally drunk on Burgundy wine, accompanied by Gorgonzola cheese sandwiches, with wife and toddler at Davy Byrne’s pub on Duke Street. The spell was still on me recently when, visiting Trieste to research the poet Rilke for a novel, I became fascinated with Joyce's years scraping a living in that city which so curiously resembles Dublin–both being built in an arc upon a bay, one facing east, the other west, with a uterine canal in the center: both built around invaders' castles ... after drinking coffee in the Stella Polare café, where Joyce got thrown out after a reading of “Dubliners,” I made a pilgrimage to the house on Via Donato Bramante where he wrote the first words of “Ulysses”; a house, I noticed, whose windows looked out upon the dark, fake-Gothic tower of the Trieste National Observatory, which I was certain in my own mind had informed his choice of the Martello tower that started it all and my heart was going like mad as I saw it and yes I thought, yes, I will write that for the Echo, Yes ...

George Foy teaches creative writing at NYU and is author of “Finding North: How Navigation Makes Us Human,” among other books.

George Foy.

BLASPHEMING THE BLASPHEMER / KEVIN HOLOHAN

“Oh God! Here it comes! Here’s where I gave up the last time!”

The steps on the National Library. All that smart banter. Can’t follow it. Can’t stand it. Just flick past it!

Oh God! What’s this now? More allusive banter about Parnell?!? Can’t follow it. Can’t stand it. Can’t be arsed!

[Hurls book to floor. Exit.]

And so it went. Each time a little further into the book. Each time a new stodgy bit to be blipped over or struggled through. Until, in the end, end of a long day, finally I realized, if that is not too strong a word, that Stephen Daedalus and his friends were mostly annoying, self-important little bolloxes, all glibness and ostentatious learning, best avoided or ignored. Mr. Joyce may have enjoyed writing them but that did not mean I had to enjoy reading them or, in fact, read them at all. The understanding that I much preferred the company of Leopold Bloom in his wanderings and could take or leave the ruminations of Mr Joyce or his mini-me Stephen was my way to enjoy Ulysses - well, about half of it.

As for the other half, maybe on some re-reading (and there probably will be another) I may find Stephen a little less annoying. Still, much more apt to turn to “Dubliners” to get a good Joyce fix. Frankly, though, life is too short and getting shorter, so, when it comes to books that endure and grow, trusted companions along the trajectory of life, I will probably always return to Mr. Beckett’s “I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now…” or Sr. Cervantes’ “En un lugar de la Mancha...” over Mr. Joyce’s “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan….” They are, admittedly, much more challenging to commemorate with a pub crawl, but, there you have it!

Kevin Holohan grew up in Dublin, where his novel “The Brothers’ Lot” is set.

Poets Patrick Kavanagh and Anthony Cronin at Monkstown Church on Bloomsday 1954.

FOR THE RECORD / ELIZABETH O’REILLY

Bloomsday celebrations always bring me back to the book, and to my 22 CD boxed set of Ulysses. For me they go hand in hand. Jim Norton reads the bulk of the book, and I was a big fan of his prior to this purchase, but Marcela Riordan reads Molly's soliloquy and it is truly immersive. I just listened to Molly's soliloquy and my preference is to read along as I listen. Listening takes care of punctuation cues. It's great to read, but the auditory component really adds to the experience. The CD sleeves also show how sections are broken down, so it's easy to take a break or to re-listen to something in particular. As often happens I'm out of town for Bloomsday. I used to love to go to Symphony Space in Manhattan for Bloomsday, but there's something intimate about reading and listening to Molly somewhere quiet, on my own. It is hilarious, poignant and sensual in equal measure.

Artist Elizabeth O’Reilly, who is originally from West Cork, lives in Brooklyn.

Jim Norton in 2001. [Photo by RollingNews.ie]

DEFENDING THE NOVEL / STEPHEN BUTLER

My individual history with “Ulysses” begins in the summer of 1993, when I purchased, at the Shannon Duty Free, a bargain book housing “Dubliners,” “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” and “Ulysses,” all in the one volume. For the next few years, I struggled through all three texts, but struggled most mightily of course, with the Blue Book of Eccles. I'm fairly certain I had the Cliffs Notes on “Ulysses” borrowed from the Maspeth Library for the better part of two years. In my senior year of high school at Cathedral Prep my AP English teacher, Brian Payne allowed me to compose my first, forgettable work on the subject. Later, when I was a graduate student at CCNY, I took a wonderful seminar on the novel with the late and much lamented Bill Herman. As a PhD candidate at Drew I wrote a piece defending the novel against a savage attack by a literary critic (and Drew alumnus) named Dale Peck. Over the last decade and a half I have presented conference papers on the pirating of “Ulysses” by the notable American pornographer Samuel Roth, and on the role of American Irish Catholics such as John Quinn, Martin Conboy and Martin Manton in the three obscenity trials surrounding “Ulysses.” I covered the reception of Joyce in general, and “Ulysses” in particular, in my book “Irish Writers in the Irish American Press.”

But this listing of the scholarly work I've done with the novel obscures to a large extent the greatness of “Ulysses.” Yes, Joyce self-consciously set out "to keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what [he] meant." But he also set-out to write an epic of ordinary everyday life in a contemporary city. While the novel begins with the dense theological and philosophical ruminations of Stephen Dedalus, the patron saint of would-be young artists rebelling against faith and family and homeland, the bulk of the book is actually about a much more accessible character, a husband and father whose profound concerns are much more mundane: family, politics, religion, work, birth, death, love, loss, marriage, sex, memories. The day celebrating the novel is called Bloomsday because Leopold Bloom is the fully formed human character at the center of the book. And of course his wife Molly is the fully formed human character whose sleepy monologue ends the book.

After almost 30 years since I first laid eyes on Joyce’s words, here’s my advice. Forget the professors and the Cliffs Notes. Take “Ulysses” down off the shelf and turn to a random page in the middle of the book and take pleasure in reading something deeply insightful about being a human: “Glowing wine on his palate lingered swallowed. Crushing in the winepress grapes of Burgundy. Sun's heat it is. Seems to a secret touch telling me memory. Touched his sense moistened remembered. Hidden under wild ferns on Howth below us bay sleeping: sky. No sound. The sky. The bay purple by the Lion's head. Green by Drumleck. Yellowgreen towards Sutton. Fields of undersea, the lines faint brown in grass, buried cities. Pillowed on my coat she had her hair, earwigs in the heather scrub my hand under her nape, you'll toss me all. O wonder!” (8: 897-904)

Stephen Butler is Clinical Associate Professor of the Expository Writing Program at NYU.

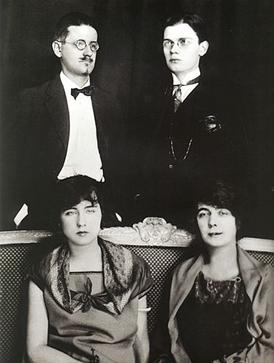

James Joyce and Nora Barnacle with their children, Lucia and Giorgio in 1924.

CRITICAL SUPPORT / JANE APPLEGATE

We all know “Ulysses” tells the tale of Molly Bloom, her husband and her lover…and we know James Joyce openly loved and appreciated the women in his life. I had not read the ground-breaking novel in school. I started reading it while doing research for a television series I’m developing about famous men and the women who contributed to their success. The pilot, “Remarkable Women: The Tale Behind Ulysses,” will screen in Dublin on Bloomsday.

Our film describes the six women who supported the writing and publication of “Ulysses”: Nora Barnacle Joyce was his muse and mother of his children; Sylvia Beach published early editions of the novel, with help and guidance from Adrienne Monnier; Harriet Shaw Weaver, a British heiress and activist provided the Joyce family with more than €1.5 million in today’s money; two American publishers, Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson, were convicted of obscenity in a New York Court for publishing extracts of the novel in The Little Review.

Jane Applegate is a film producer.