[This piece was originally published in the Irish Echo on Jan. 16, 2013, against the backdrop of the debate sparked by the Sandy Hook massacre.]

Fifty years ago, America had a president who was greeted rapturously wherever he went in Latin America and Europe. The reaction was the same at home. But he was cut down in broad daylight in Texas by an assassin using a mail-order rifle. They said at the time that the nation had lost its innocence.

Then they said it again when men who’d asked for flight lessons, but weren’t interested in learning how to land, flew planes into the World Trade Center, destroying it and killing thousands.

But nobody said it after Dec. 14 last, when 20 schoolchildren aged 6 and 7 were slaughtered by means of legally held weapons. The main reaction from citizens, apart from numbness and grief, was one of utter frustration and despair at the NRA’s failure to take even a modicum of responsibility for the tragedy.

You could say that in certain ways, some Americans simply refuse to lose their innocence. I heard a guy on the radio after one of the earlier 2012 massacres say that he’d became a convert to gun rights while serving in the Peace Corps in the Philippines, because he saw how the military treated the people. He seemed blissfully unaware that his own government backed strong man Ferdinand Marcos’s wars against Maoist and Islamist insurgencies, or that our Constitution allows for the suppression of rebellion and disorder.

The innocence has been preserved in part because this country never faced serious internal paramilitary or terrorist threats during the 20th century. Many of the county’s closest democratic allies and friends did. Britain, Ireland, Italy, Germany, Spain, India and Israel, to name a few, have thought it prudent, and for perfectly sound political and security reasons, not to allow unfettered access to weapons. And given that in several of the above examples, U.S. officials and business people were targeted by extremist groups, our government was most thankful that gun-control measures were strictly enforced in those democracies (and also in others, too, like France, Japan and Greece).

There are other realities about which some would rather remain innocent (or ignorant). One is that the means to kill quickly and on a mass basis increases over time. The novelist Peter Quinn (“Hour of the Cat” and “The Man who Never Returned”) has made the point in this vein that 19th century racial theories combined with 20th technology made the Holocaust possible.

This is why advocates want gun control. They are not calling for a ban on all weapons, but they do say that ownership must be subject to the strictest regulation. There’s a long tradition of that in the American republic. In new territories in the 19th century, for instance, the enactment of gun strictures was often part of the civilizing process.

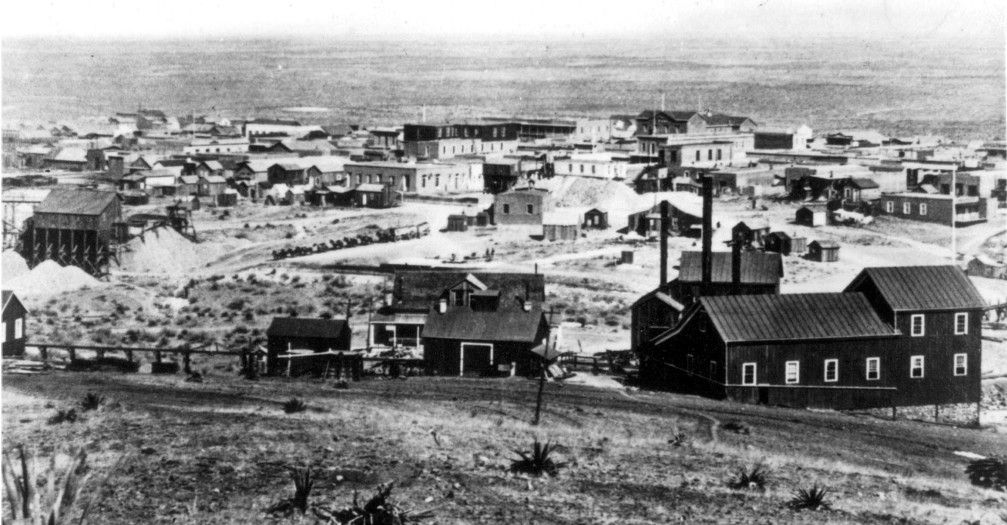

Historian Ross F. Collins has written: “Pioneer publications show Old West leaders repeatedly arguing in favor of gun control. City leaders in the old cattle towns knew from experience what some Americans today don’t want to believe: a town which allows easy access to guns invites trouble.

“What these cow town leaders saw intimately in their day-to-day association with guns is that more guns in more places caused not greater safety, but greater death in an already dangerous wilderness,” according to Collins, “By the 1880s many in the West were fed up with gun violence. Gun control, they contended, was absolutely essential, and the remedy advocated was usually no less than a total ban on pistol-packing.” Collins, the author of “Gun Control and the Old West,” cites editors who paid lip service to the “right to bear arms,” but clearly felt it wasn’t absolute and even mocked it. The editor of Laramie’s Northwest Stock Journal said in 1884: “We see many cowboys fitting up for the spring and summer work. They all seem to think it absolutely necessary to have a revolver. Of all foolish notions this is the most absurd.”

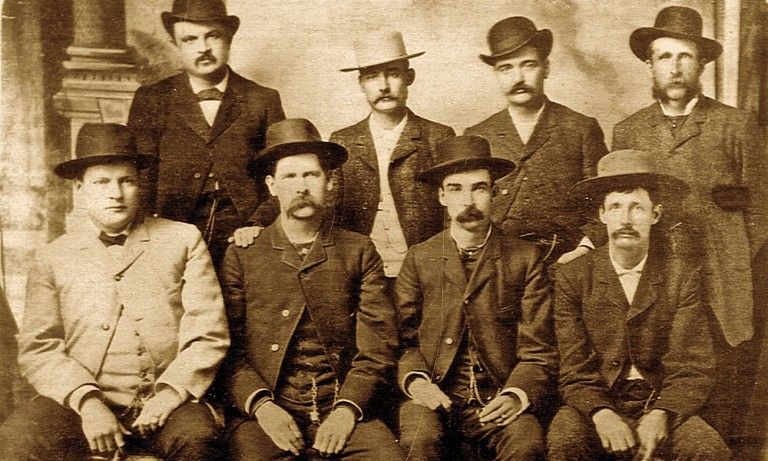

Wyatt Earp, one of the most famous and controversial lawmen in the Old West, was a strong proponent of gun control. That was the pretext when Earp, his two brothers and Doc Holliday confronted the McLaurys and Billy Clanton before the famous Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on Oct. 26, 1881. Tombstone in Arizona Territory had passed an ordinance that required people deposit guns and knives at a livery or a saloon upon entering the town.

Wyatt Earp, 2nd from left in front row, pictured with other members of the Dodge City Police Commission in 1883. Earp believed in the strict enforcement of gun control.

The Second Amendment says: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Gun-rights advocates stress the individualist right to keep and bear arms, whereas the gun-control side look to the collectivist “well-regulated militia.”

The Supreme Court voted along that divide in a landmark 2008 decision, with the conservative majority of five backing the individual right position. Justice Stevens of the minority moderate/liberal group said that his colleagues’ reasoning was “strained and unpersuasive” and argued that the right to possess a firearm exists only in relation to the militia.

Liberals say that for someone who is concerned about the “original meaning” of the Framers’ words, Justice Antonin Scalia has gotten it badly wrong with regard to the Second Amendment. Whatever the case, there has been a noticeable lurch to the right in the court over the past two decades. Back in 1990, the originalist, conservative-leaning former Chief Justice Warren Burger opined: “The Gun Lobby’s interpretation of the Second Amendment is one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word fraud, on the American People by special interest groups that I have ever seen in my lifetime.”

Gun-control advocates also point to the nuanced statements of Founding Fathers like John Adams. In 1787, the man who would become the second president said: “To suppose arms in the hands of citizens, to be used at individual discretion, except in private self-defense, or by partial orders of towns, countries or districts of a state, is to demolish every constitution, and lay the laws prostrate, so that liberty can be enjoyed by no man; it is a dissolution of the government. The fundamental law of the militia is, that it be created, directed and commanded by the laws, and ever for the support of the laws.”

The Founding Fathers were revolutionaries, but they were men of property, too, (and some of them had slaves) and so were careful not to issue an insurrectionist’s license.

When the Militia movement sprung up in the 1990s, scholars — libertarians among them — were quick to say that the Founding Fathers only agreed with the right to revolt if the people acted as a whole, or if there were at least a huge degree of consensus; furthermore it could only be as a last resort against a genuinely tyrannical regime.

Unfortunately those qualifications aren’t generally cited by people like Kevin D. Williamson, a writer with National Review, who said approvingly in a post-Newtown massacre column: “The purpose of having citizens armed with paramilitary weapons is to allow them to engage in paramilitary actions.”

Would he be so casual in his use of language if our policemen and soldiers faced a real domestic threat from the extreme left or right or some other source?

Williamson and his ilk never satisfactorily address an issue I raised in an opinion piece after the Aurora killings in July. Authoritarian rule has often come through an alliance of armed militias in civil society and their facilitators in the armed forces and government generally. This is what happened in Germany. The Freikorps, mainly organized bands of right-wing World War I veterans, helped the Nazis rise to power. The armed, violent Nazi movement itself took on political enemies on the streets and generally fomented chaos before ever making an electoral breakthrough.

History has disproved time and again the notion that arms in the hands of citizens are bulwarks against tyranny. We have indeed seen militias, in Adams’s words, “demolish every constitution and lay the law prostrate.”

The National Review’s Williamson, though, mocked as “soft-headed” fellow conservatives who’ve suggested that the Second Amendment was just about shooting “Bambi and burglars.” Instead, he said, it’s about “our ability to oppose enemies foreign and domestic.”

In the real world, however, and in the absence of well-regulated militias representative of the people as a whole — those from all socio-economic groups, races and creeds — paramilitary weapons have nothing to do with protecting the Constitution and must always be regarded as a threat to society and to democracy.