In the early 2000s, I had dinner with Fr. Daniel Berrigan. Though Berrigan had become a celebrity to some people, I was struck by his humbleness, modesty, and meekness. Berrigan had an aura that is difficult to put into words. It was hard to believe that this meek priest had been arrested hundreds of times and repeatedly sentenced to prison for his protests. J. Edgar Hoover and Cardinal Francis Spellman even considered Berrigan an enemy of the state and of the church respectively; however, he received some of his greatest praise from Pedro Arrupe, S.J., superior general of the Jesuits in Berrigan’s day, who said, “Dan Berrigan is the greatest Jesuit of the [20th] century.” A highly controversial and polarizing figure, Berrigan fervently believed in Christ’s message of non-violence and felt compelled to bear witness against militarism, nuclear arms, racism and injustice. Some labeled him a “Christian anarchist.” Along with his brother Fr. Phillip Berrigan, Daniel became the first priest in U.S. history to be arrested for anti-war activism. Energizing the movement against the Vietnam war in the 1960s, Berrigan forged a tradition of pacifist protest that lasted a generation.

Berrigan was born into an Irish Catholic family in Virginia, Minn., on May 9, 1921. His father was a socialist, farmer, railroad engineer and poet who raised his six sons on a small farm near Syracuse, N.Y. Imbued with a deep Catholic faith from his childhood, Daniel joined the Jesuits straight out of high school at age 18. In 1952, 13 years later he made his final vows, becoming a Catholic priest. He began teaching theology and French at Brooklyn Preparatory High School and then in 1957, he was appointed professor of New Testament Studies at Le Moyne College in Syracuse. That same year he won the prestigious Lamont Prize for his book of poems “Time Without Number.” On sabbatical, Berrigan traveled to France where his world view was transformed by the examples of worker-socialist-priests whose notions of pacifism and civil disobedience profoundly affected him. Berrigan came to the self-realization that his life goal was to help bring Jesus’s teachings into the secular world.

He returned to Europe during the summer of 1963, where profoundly moved by his contact with persecuted Eastern European priests in Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. In Eastern Europe, he saw a dramatically different Catholic Church – one that attacked the status quo and dared to speak truth to power. Berrigan hoped that the American Catholic Church would similarly challenge the status quo. He soon became one of the most outspoken Catholic priests, denouncing civil rights abuses in the South and supporting Dr. Martin Luther King.

In 1964, before it was fashionable, Berrigan and his brother Phil spoke out against America's rapidly increasing intervention in Vietnam. His anti-war stance pitted him against some other Jesuits and particularly some bishops, who denounced their supposedly anti-American activism. Berrigan, along with pacifist David Dellinger, helped draft a "declaration of conscience" urging young men to resist the draft. A year later, he joined Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin, Jr., and others in a coalition of churchmen called Clergy and Laity Concerned about Vietnam. He caused even more controversy when the following year Berrigan, along with Professor Howard Zinn and Tom Hayden, the leader of Students for a Democratic Society, flew to Hanoi, North Vietnam, to receive three prisoners of war who had been released by the government.

In May 1968, Daniel, his brother Philip and seven others walked into the Selective Service office in Catonsville, Md., and coolly emptied the contents of draft files into wire trash baskets, doused them with home-made napalm, and burned them. They then joined hands and prayed, calmly awaiting their arrests. The trial of the Catonsville Nine sparked a media frenzy, highlighting Catholic opposition to the increasingly unpopular war. As The New York Times noted in Berrigan's obituary, his actions helped "shape the tactics of opposition to the Vietnam War.” The Berrigans were convicted in a trial covered nationally and each given two-year sentences.

The Berrigans appealed the decision and, while out on bail, they went on the run. Philip was captured only 11 days later, but Daniel remained in hiding for four months, even making sensational public appearances, while the Federal Bureau of Investigation vainly pursued him. In August 1970, he was finally captured and sent to the Danbury, Connecticut, Correctional Facility, where he wrote several volumes of poetry. On Jan. 25, 1971, Daniel and Phillip’s pictures graced the cover of Time magazine, whose headline read: “Rebel Priests: The Curious Case of the Berrigans.” Daniel later wrote a play entitled “The Catonsville Nine,” which ran off-Broadway and was made into a 1972 film starring Gregory Peck. Many claim that "the radical priest" in Paul Simon's hit song "Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard," refers to Berrigan.

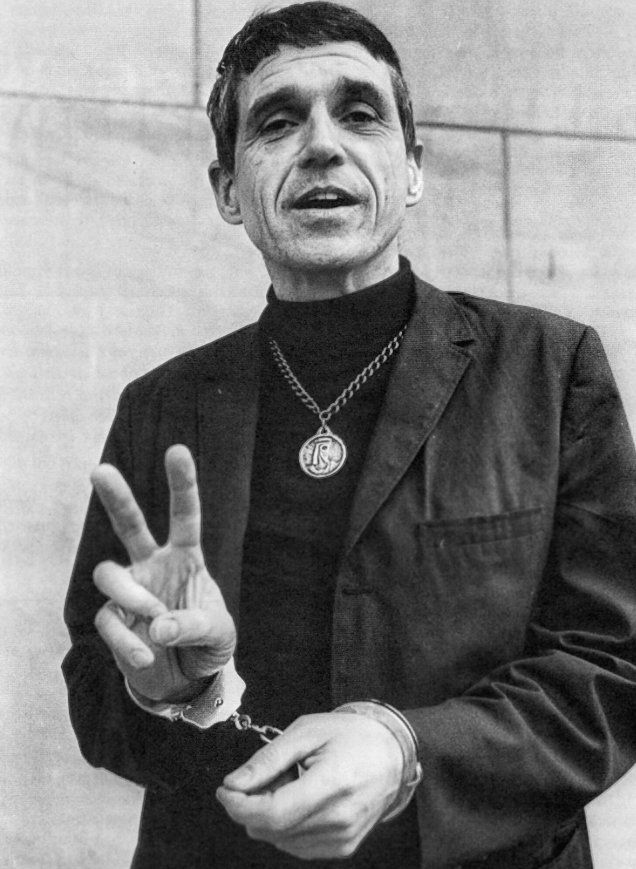

The Rev. Daniel Berrigan S.J. pictured after one of his numerous arrests protesting war.

Berrigan continued his activism throughout the 1970s, consistently denouncing American imperialism and the “war-making sins” of the government. On Sept. 9, 1980, Berrigan, his brother Philip, and six others, known as the Plowshares Eight began the Plowshares movement when they entered the nuclear General Electric nuclear missile plant in King of Prussia, Pa., damaging nuclear warhead nose cones and pouring blood onto documents and files. Arrested and charged with over 10 different felony and misdemeanor counts, Berrigan and the others eventually ended up serving just under two years in prison. Daniel’s legal battle was re-created in Emile De Antonio’s 1982 film “In the King of Prussia,” with Berrigan playing himself and Martin Sheen acting a leading role.

From 1970 to 1995, Berrigan spent a total of nearly seven years in prison for various offenses related to his protests. His brother Phillip left the priesthood, but Daniel always remained true to his vows. Berrigan also wrote or co-authored more than 50 books, including numerous volumes of poetry. In addition, he also penned works on Old Testament prophets including Ezekiel, Isaiah and his namesake, Daniel, whom he portrayed as a rebel who defied wrongful authority. In his later years, Berrigan continued to protest and be arrested but he became increasingly annoyed by the political apathy of Americans and noted wistfully that his arrests did not draw the same level of publicity that they previously had.

Berrigan grew older, but never abandoned his core beliefs. He opposed American intervention in Central America, the war in Iraq and American militarism and imperialism. In the final years of his life, he worked with those suffering from AIDS. In 2016, Daniel Berrigan passed away at age 94.