For 75 years, America’s most powerful politicians have come to New York City for the Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner. Presidents Obama, Clinton and Trump have all been keynote speakers at the A-list charity event, but Smith’s remarkable biography and achievements as governor today are largely forgotten. Smith, though, deserves a special place in the pantheon of great Irish-American New Yorkers.

Part of what makes Smith such an extraordinary success is the humbleness of his birth. Born in 1873 in a tenement flat in one of the poorest areas of Manhattan, the infamous fourth ward, Smith, always took pride in growing up there and chose to live in the neighborhood, even after he became New York’s governor. The grandchild of immigrants from Westmeath and Cavan on his mother’s side, Smith always considered himself to be of Irish descent, though he was also part German and part Italian. Smith, who spoke with his distinctive New York City accent, embodied the Irish-American working-class New Yorker.

The future governor knew poverty and hardship from an early age. His father, who owned a small trucking company, died when Al was just 13, so he dropped out of school to work to support his mother and sister. Smith’s mother, who had a deep influence on her son, always insisted that Al have fun whatever he was doing in life, whether running for president or working in the fish market, a lesson Al never forgot. Despite the poverty of his youth, Smith showed vivacity, humor and concern for others, traits that made him a natural politician. His “well-timed humor” won him many a political debate and both Republicans and Democrats recalled that when his speaking time was up and the gavel came down, that Smith would laugh with “boyish surprise” and continue to speak as the members laughed and shook their heads. His onetime friend and political ally Franklin Roosevelt dubbed Smith, “the happy warrior,” a moniker that fit the gregarious and witty son of the fourth ward.

Never attending high school or college, Smith always claimed he learned about people by studying them at his first job at the Fulton Fish Market. Years later, when he was a state assemblyman, a group of his fellow legislators, discussing their elite social and educational backgrounds, inquired about his academic pedigree: Smith answered, “FFM.” Greatly confusing his fellow lawmakers. Then Smith replied: “Fulton Fish Market!” It was that “degree” that made Alfred E. Smith the man that he was, a man who grew to understand the workings of human nature and made him a “man of the people” and identified with the working-class and the immigrants who arrived in the United States with hope in their hearts.

Smith also acted on Vaudeville stages where he developed the oratorical skills that would later make him a successful politician. He got his start in politics, campaigning for the Tammany machine, which rewarded him with a job as a process-server for the Commissioner of Jurors, when he was 21. Eight years later, Tammany successfully ran him for the State Assembly. When Smith arrived in Albany, he was intellectually overwhelmed by the demands of being a lawmaker, but Smith resolved to understand how the legislative process worked. He began to peruse the bills on his desk, and also read up on them until late in the night at the New York State Library, soon becoming one of Albany’s most knowledgeable lawmakers. The head of the Citizens Union, a good-government group not in the habit of praising Tammany men, declared that Smith "displayed a practical knowledge of the workings of state government not rivaled by anyone else."

Though Smith started as a Tammany Hall machine politician, he helped change the machine into a force for bettering the lives of the urban poor and the working class. He soon befriended another Tammany Hall politician Robert Wagner, who would become Smith’s ally in reform efforts. When the Democrats gained control of the state legislature in 1911, Smith became majority leader and chairman of the all-important Ways and Means Committee. Smith and Wagner began to emerge as champions of progressive legislation to help New York’s poor and vulnerable. When the terrible Triangle Shirtwaist Factory of fire of March 1911 claimed the lives of 146 young immigrant women, Wagner and Smith headed a Factory Inspection Commission that investigated hundreds of factories and led to thirty-eight new laws regulating labor. Smith combined compassion for the working poor with an uncommon skill for crafting and passing legislation and in the process, he transformed Tammany's reputation from mere corruption to a force to help protect the state’s workers.

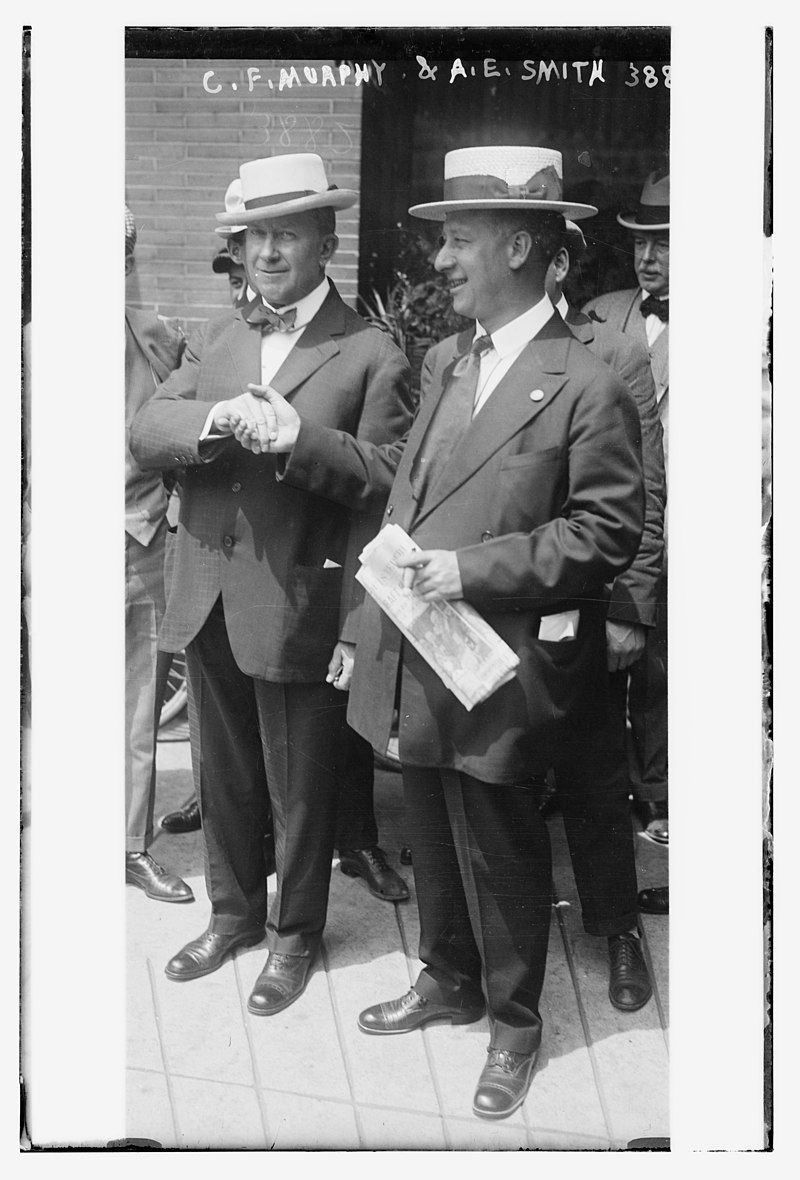

By 1915, Tammany boss Charles Francis Murphy began to groom Smith for higher office. In 1917, he was elected president of the city’s Board of Aldermen. The following year, Smith narrowly defeated a powerful Republican incumbent to become the state’s first Irish Catholic governor, with wild celebrations breaking out in Irish neighborhoods across the state. He served from Jan. 1, 1919, through Dec. 31, 1920. After losing in the Republican landslide of 1920, he was reelected three times, and served from Jan. 1, 1923 through Dec. 31, 1928. In his combined eight years in office Smith proved to be one of the most effective governors in state history, pushing through scores of reform bills making New York a model for progressive government. His reforms included equal pay for women teachers; tenement reform; state funding for education increased from $9 million to $82 million; strengthening worker’s compensation; expanding civil service; streamlining state government, combining 129 agencies into 20; adoption of cabinet government; and creating a massive state parks program.

By 1924, there was a movement to nominate Smith to be the Democratic Presidential nominee, but this era was the height of the Ku Klux Klan, and many Democrats were also Klan members and avowed anti-Catholics. After more than 100 ballots, Smith lost the nomination. Four years later, he was even more popular and when the convention gathered in the summer of 1928, there was no denying him the nomination.

In 1928,Smith became the first Catholic ever nominated by a major party to be president, but he still faced huge obstacles. The Klan had millions of adherents across the country and many Protestants were horrified not only by Smith’s religion, but also by his working-class New York accent. Jovial by nature, Smith was stunned by the vicious editorials and speeches made by anti-Catholic demagogues. In the spring of 1927, the prestigious Atlantic Monthly published “An Open Letter to the Honorable Alfred E. Smith.” Written by Charles C. Marshall, an eminent lawyer and member of the Episcopal Church, which drew upon 19th-century papal encyclicals condemning separation of church and state and freedom of religion, it suggested it was impossible for a faithful Catholic to adhere to the Constitution and uphold the oath of office as President. On the campaign trail outside the big cities, Smith was sometimes greeted by throngs of admirers, but also by burning crosses and crowds of hostile bigots.

On election day, the Democrat was crushed. Hoover garnered 58 percent of the popular vote (and 444 electoral votes) to Smith’s 41 percent (87). Even his home state of New York went for Hoover, leaving Smith victorious in only Massachusetts and six Southern states that after the Civil War still couldn’t bring themselves to vote for a Republican. To run for President, Smith had had to give up the governorship. On the day Smith lost the Presidency, Franklin Roosevelt had won the gubernatorial race. Smith had acted as FDR's patron but had always had a hard time taking him seriously; Roosevelt seemed to Smith clever and charming, but also ditsy and insubstantial. Out of office, Smith seems to have envisioned an arrangement under which Smith would maintain power in Albany while Roosevelt served as a figurehead. Roosevelt balked at this idea, leading to bitterness between the two men.

After losing the presidential race Smith needed a job, so he created for himself the post of president of the Empire State Building Corporation. With great fanfare, Smith announced, on Aug. 29, 1929, plans for the construction of the world's tallest building. Two months later, though, following the stock market crash, Smith lost his personal savings and the Empire State Building proved to be a white elephant. During its first year, it had a vacancy rate of 75 percent, and hovered on the brink of foreclosure.

In 1932, he decided to run against Roosevelt for the Democratic Presidential nomination and lost. F.D.R. had been in office only a few months before Smith began attacking the New Deal. It was too theoretical, he wrote in a magazine column—the effort of a "man who has been sitting in the library, writing books and lecturing to students." It concentrated too much power in Washington. It wouldn't work. Smith declared. His attacks on Roosevelt and his New Deal alienated many Democrats.

Smith died in 1944, but few Democrats mourned his passing because of the enmity he showed President Roosevelt, and New Yorker’s extraordinary legislative achievements were also hardly spoken of. In Smith's honor, however, the Diocese of New York established a foundation to benefit the Catholic Charities, and, ever since, one of the key political events in New York has been the foundation's annual fund-raiser, the Al Smith dinner, held each fall during the election season. Democratic Presidential nominee John F. Kennedy, speaking at the dinner in 1960, best eulogized Smith stating, "The bitter memory of 1928 will fade, and all that will remain will be the figure of Al Smith, large against the horizon."