I recall clearly a conversation with my uncle, Michael O'Shea, shortly after I came to New York in the early seventies. He and his older brother, Paddy, were active in the Irish War of Independence. My query centered on why they had taken the anti-treaty side in December 1921.

He explained that the Volunteer group that they trained with attended mass every Sunday in the village of Ardgroom in West Cork, just over the Kerry border from their home in Lauragh.

After the church service, they proceeded to a designated secluded area about two miles out the road where their leader, Liam O’Dwyer, would announce plans for the coming week.

Towards the end of his instructions on the Sunday after the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in London, on Tuesday, December 6th 1921, he told them that “a crowd in Dublin want us to abandon our oath to the Republic. Needless to say, we will have nothing to do with that. See you on Wednesday. Company dismissed.”

The oath was indeed the central point of contention in the debate that was so intense that it led to an awful civil war. All the members of the Irish Republican Army who had fought the British forces to a standstill over the previous two years, pledged solemn allegiance to the aspirational Irish republic, but the proposed treaty would entail every member of the new Irish parliament taking an oath of fealty to the British monarch.

Many people afterwards believed that the deadly cleavage among former comrades arose because of disagreements about the partitioning of the country. In fact, the Government of Ireland Act setting up the Northern Ireland parliament was signed into law in Westminster a year earlier in December 1920. Partition was only mentioned once during the Treaty debate in the Dail.

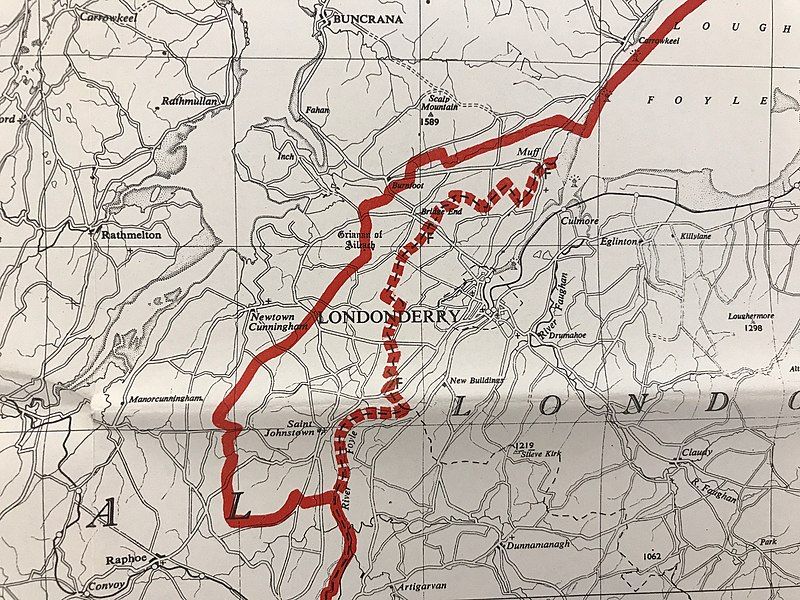

The Boundary Commission promised in the Treaty was the best that nationalists could do. Griffith and Collins believed that this group of three, one from Dublin, one from Belfast plus a British chairman, with terms of reference that included respect for the wishes of local communities, would cede Derry and Tyrone to the southern government, leading eventually to the whole arrangement crumbling.

The civil war intervened with Griffith and Collins going to early graves, resulting in very few changes by the Commission to the partition map. The parties failed to agree even on these minor land adjustments, so they left the original border unchanged. The full text of the Commission report was not made public until 1969.

Also, despite the acrimony in the South, Republicans never favored fighting a war for unification. They knew that any belligerent actions to that end would invite determined opposition from the loyalist Ulster Volunteers whose raison d’etre was never to be ruled by Dublin. Also, fighting fellow-Irishmen would run completely counter to Wolfe Tone, the honored originator of republicanism’s clear message of uniting Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter.

A page of the Treaty as annotated by Arthur Griffith.

The broad terms of the Treaty were known in advance. De Valera, the elected president of the Provisional Dail, had met with the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, five times since the truce between the two armies was agreed on July 11th 1921. They didn’t relate well to each other, but they both wanted peace and the issue of the degree of sovereignty of the new Irish state became the big stumbling block.

The Irish were offered all the freedoms of Dominion Status enjoyed by Canada and other members of the British Commonwealth. Michael Collins pointed out that this level of independence ended British rule in most of Ireland after 750 years of occupation.

He made two other significant points explaining his support for the proposed terms. First, he said that accepting the invitation to negotiate meant that compromises were inevitable. Second, he pointed out that the agreement they reached was not “the ultimate freedom that all nations aspire to but the freedom to achieve it.”

De Valera had argued for “External Association” for the new state. This would mean that for all internal matters Ireland would function as a republic but would cede to British interests in external affairs. It was an ingenious proposal which, he was assured, would satisfy Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack, the two hardline cabinet members voicing strong opposition to the December 6th document.

It did not, however, meet the standard of purists like Mary McSwiney and Liam Mellows for whom any deviation from an All-Ireland republic was unacceptable. More tellingly, the de Valera idea was formally proposed by the negotiators in London on three occasions and firmly rejected by the British side.

Prime Minister Lloyd George’s Liberal Party was the minority group who with the majority Tories formed the governing coalition. Some historians opine that the PM could have lived with Dev’s idea, but the Tories were unalterably opposed, unfortunately, dooming the proposal.

Some historians claim that if the Dail voted on the treaty document before the TDs went home for Christmas, it would have been defeated. However, the people throughout the country wanted peace and that sentiment swayed a number of the parliamentary representatives.

As the negotiations wound down the prime minister issued a warning to the Irish: if you reject this treaty, expect “immediate and terrible war.” Many historians believe he was bluffing, pointing out that a war in Ireland registered as very unpopular, especially in America. His military leaders told the PM that to defeat the IRA, a determined guerilla army, would involve “taking the gloves off” and enforcing an indiscriminate shoot-first policy – effectively, a reign of terror.

Michael Collins did not dismiss his threat. He knew that members of the IRA, especially the flying columns, were tired of rough living and short of arms. He was also wary of the impact of the aerial spying and bombardments that the British had recently started to use.

Some historians claim that if the Dail voted on the treaty document before the TDs went home for Christmas, it would have been defeated. However, the people throughout the country wanted peace and that sentiment swayed a number of the parliamentary representatives. The decision in favor was made on January 7th a hundred years ago by a narrow margin of 64 to 57.

The preference for peace was solidified six months later in the general election in June when pro-treaty candidates easily defeated (681,000 against 486,000) their opponents whose main message was that the Treaty involved a sell-out to the British.

In April, some hardline Republicans occupied a few places in central Dublin and the Four Courts, a major administrative building. In June, the government, under pressure from British leaders, asserted their authority and forcibly captured the Four Courts.

That ignited the Civil War, a horrendous series of small battles conducted with fierce intensity and often with merciless murders and frequent retaliatory cruelty.

Liam Lynch, the Pearse-like, idealistic Cork revolutionary, who was leader of the insurgency, died on April 14th 1923. Frank Aiken took over as chief-of-staff and, prompted by de Valera, ended the civil war before the month of May arrived.

Back to that conversation with my uncle. He remembered that one Cork man named O'Sullivan announced to the group that he was taking the pro-treaty side.

He never saw or heard from that man afterwards, but he often thought of his extraordinary moral courage that day at the rebel gathering near the village of Ardgroom.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com