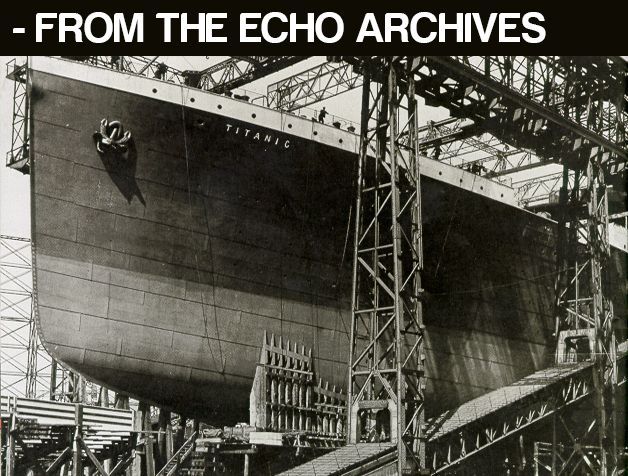

TAKEN FROM THE IRISH ECHO ARCHIVES: APRIL 2012

On a sharp-edged December day, with snow on the hills circling Belfast, I stood close to the edge of the man-made crevasse that is the dry dock where Titanic was born.

It's a sight to take in slowly because as you stare into the cavernous space the emptiness starts to fill in. You see the Titanic in your mind's eye and, almost unconsciously, you raise your eyes to a level at which you imagine the great ship once soared.

We are all spoiled a bit of course. Compared to the floating cities that are the world's biggest cruise ships today, RMS Titanic was modest in size. 1912, despite all its gilded finery, was indeed a more modest time, at least in engineering terms. But make no mistake, to have seen the Titanic with your own eyes would have transfixed even the most jaundiced with wonder.

It was the Jumbo Jet of its day, a Saturn 5 rocket, an empress of the waters. And she was doomed from her first moment of life. But not doomed to obscurity. Titanic, as we all know, looms larger today than she ever did in her short existence. She is a vessel that inhabits the big screen, the printed page, the boundless mind, and to a degree that exceeds any other ship that ever floated.

In a sense, Titanic really has proven unsinkable. Millions around the world only have to spare her a moment's thought and there she is in all her four-funneled glory. Of course, the imagination is always sharpened by the advantage that is primary location. You can stand in Belfast's Titanic Quarter and an array of buildings, exhibits, and that great empty dry dock, will draw you deep and deeper into the story.

The White Star Line's brightest star parted the waters in only four ports: Belfast, Southampton, Cherbourg and Queenstown, now Cobh. She was supposed to put in at Liverpool, her port of registration, on the way from Belfast to Southampton, but this plan was cast aside at the last minute. New York awaited, and time was precious, not to mention money. Of course, New York would always wait.

There has been, inevitably, a degree of competition surrounding the 100th anniversary of the Titanic's sinking, just as there was competition between shipping lines in a time when transatlantic flights were still more than two decades in the future

So who wins, who has the edge in the great Titanic memory stakes? Southampton would be the port most synonymous with Titanic had the ship survived its maiden voyage and notched up years of service on the Atlantic run. Cherbourg would have been most closely associated with the ship by passengers from continental European countries, while New York would be a large part of the ship's legacy as it was the primary destination for passengers from Europe, Britain and Ireland.

Belfast's part in the story would likely have faded into the background had the ship's story run a normal course. The same would have been the case for Queenstown, later Cobh. And Addergoole in County Mayo would have been off the map altogether, though some in the village might have harbored memories of family members having once sailed to America on a ship named, well, didn't its name begin with a T?

Ah, but Titanic's true life story turned this bland scenario fully on its head.

So Belfast lays strongest claim to ownership of the Titanic story. Cobh ranks too, and two, in terms of poignancy, as it has possession of those last photographic images and also took on the last batch of passengers, 113 of them, nervous, hopeful, expectant, unsuspecting Irish men, women and children.

And Addergoole stands out because of proportions: it's tiny size against the ship's towering dimensions, and the disproportionate toll that the sinking exerted on the village and its surrounding hinterland.

It might well have been Addergoole that was represented in the classic 1958 movie "A Night to Remember," which includes a scene of Irish villagers heading off on what would have been the greatest adventure of their lives, and for some of them, the last.

Irish characters, not to mention music, were to the fore in James Cameron's 1998 eponymous blockbuster, while Hiberno-Anglo tensions that were bubbling up fast in 1912 loomed large in the Titanic mini-series which aired on one of the main networks over the recent anniversary weekend.

Those historical tensions, or at least an aspect of them, can be traced back to the building of the ship in Belfast by a workforce that was mostly devoid of Catholics.

The bows of the Titanic visitor building.

The Titanic was a ship with as many social, political and economic metaphors on board than it had lifeboats. But today, those metaphors play second fiddle to Titanic as a story with an endless allure, and the ability to lure people to its port of origin, Belfast, and its now up-and- running Titanic Quarter, once part of the Harland and Wolff shipyard.

It remains to be seen of course just how much influence Titanic will bring to bear on the economic fortunes of Belfast, and indeed the rest of Northern Ireland. But there's little doubt that the ship's legacy could turn out to be a cloud with a very bright silver lining.

As is always the case, marketing will be pivotal. In the case of the Titanic Quarter, that marketing fits in with the broader plan to sell people the idea of visiting the island of Ireland, the island's northern counties, their main cities Belfast and Derry, which will have its own moment in the sun next year as the UK's City of Culture.

In specific terms, Titanic has created not just a quarter in a single city, but a triangle on a singular island, one that is anchored on the shores of Belfast Lough, in the rolling hills around Addergoole, and in the sheltered waters of Cobh, gateway to the ending that was the beginning of the great Titanic tale, an epic that has only grown with the passing of the years.

No matter what way you cut it, Titanic's mighty bow wave is still out there.