The Irish have been in Manhattan for a long time and Lower Manhattan is full of places with strong connections to New York Irish history. Let’s take a virtual Irish history walking tour of the area and recall the area’s many Irish connections.

Castle Clinton/ Battery Park

Located at the very tip of Manhattan, Castle Clinton welcomed far more Irish immigrants than celebrated Ellis Island, which later welcomed about 600,000 Irish emigrants. Castle Clinton has not changed much since it was built in 1807, although it was converted in 1824 into a venue for concerts, speeches and grand balls. In 1851, the old fort was again repurposed as an immigration center, the largest one in the United States. An amazing two and a half million Irish immigrants would pass through Castle Clinton in its 40-year history of receiving immigrants. Once landed, Irish immigrants could get aid and advice from the Irish Emigrant Society and other charitable groups inside the structure. There was also a labor exchange that would offer the newly-arrived Irish work. In 1852, 1,000 armed members of New York’s Irish militia’s welcomed the recently escaped Thomas Meager in a public reception in his honor. Meager would go on to earn great fame as the leader of New York’s famous Fighting 69th Regiment during the Civil War.

In 1891, Castle Garden was replaced by Ellis Island. Part of the reason the immigration center there was closed stemmed from the numerous predators waiting outside the former fort for the naïve Irish immigrants who had just passed through Castle Garden. Some unsuspecting Irish newcomers were overcharged for flats or for railroad tickets, while others were tricked into joining criminal gangs. Some Irish farm girls were even tragically lured into a life of forced prostitution by smooth -alking criminals.

Home for Irish Immigrant Girls, 7 State St.

Just across the street from Battery Park is the former home for Irish Girls, one of the most successful charitable institutions the Irish ever set up in New York City. Established through the largess of Irish philanthropist Charlotte Grace O’Brien in 1883, the organization worked closely with American immigration authorities to help newly-arrived Irish women. O'Brien, an Irish immigrant herself, was concerned with the plight of poor Irish women. For a half-century the home met Irish women and offered them shelter for a night or two until relatives could arrive to bring them to their homes. If no relatives could be found, they were placed into respectable homes as domestic servants. An Irish-born staff, many of them Irish speakers, would make sure that these young women did not fall into the clutches of the predators who lurked at the Battery. The home helped over a 100,000 vulnerable young Irish women get a good start in New York City during its nearly 60 years of existence. In April 1912, the survivors of the RMS “Titanic” arrived in New York Harbor. Those from first class were whisked off to the Waldorf Hotel. Those from steerage were sent to the home.

7 State St.

The State Street building is also is a landmark for Catholic Americans. Before O’Brien purchased the mansion in 1870, it had been the home of Richard Bayley, a renowned physician and professor of anatomy at King's College. His daughter, Elizabeth, would grow up to marry William McGee Seton. She was later canonized as the first American-born saint of the Catholic Church.

Fraunces Tavern, 54 Pearl St.

The landmark tavern, which dates to 1719, has strong connections to George Washington and the American revolution, but also many ties to Irish American history. Claiming to be New York’s oldest tavern, the landmark hosted a meeting of the Friendly Brothers of St. Patrick on March 17, 1771. If the famous Irish-born spy who saved George Washington’s life twice Hercules Mulligan was not present at that St. Patrick’s day meeting, then he was surely there for the New York chapter of the Sons of Liberty, which often met there and counted Mulligan among its most important members. The Derry-born Mulligan, a character in the hit musical “Hamilton,” is credited with convincing his boarder Alexander Hamilton of the justness of the colonial’s grievances against British rule. Hamilton would later take part in the most famous night in the pub, Washington’s farewell dinner for his officers there in 1783, which included Irish-born officers.

The Cotton Exchange, India House, 1 Hanover Sq.

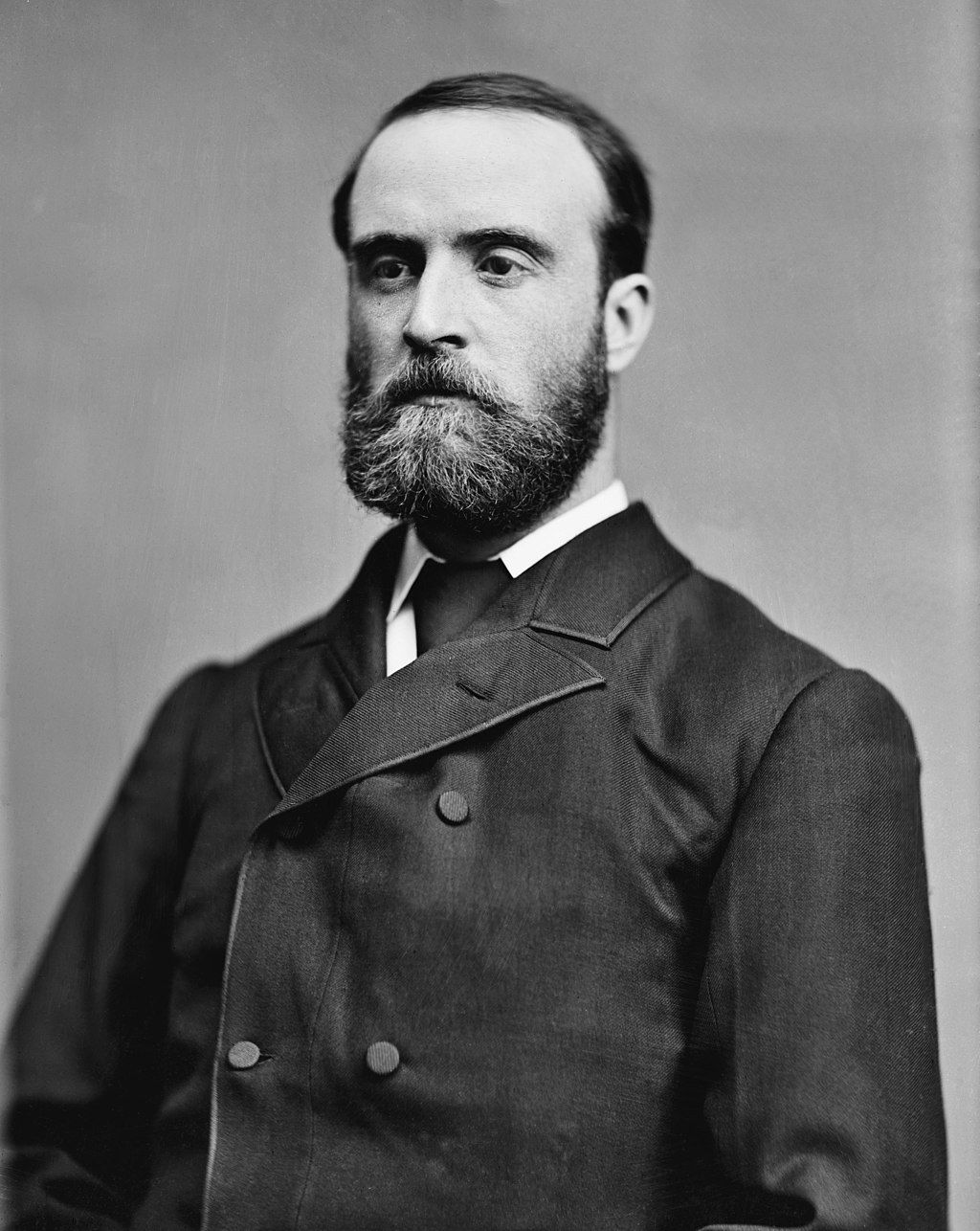

The Cotton Exchange was the home in the 1890s for W.R Grace and Co., a rich import-export firm founded by Cork-born William Russell Grace, who in 1881 would be elected as New York’s first Irish-born and Catholic mayor. A noted philanthropist, Grace founded an institute bearing his name, which until today helps to teach poor women job skills. In 1880, Home Rule advocate and parliamentary leader Charles Stewart Parnell spoke at the Cotton Exchange, asking New York’s rich merchants for donations to help farmers in the west of Ireland threatened with eviction.

Charles Stewart Parnell in a photograph taken by Mathew Brady.

White Star Line, 9 Broadway

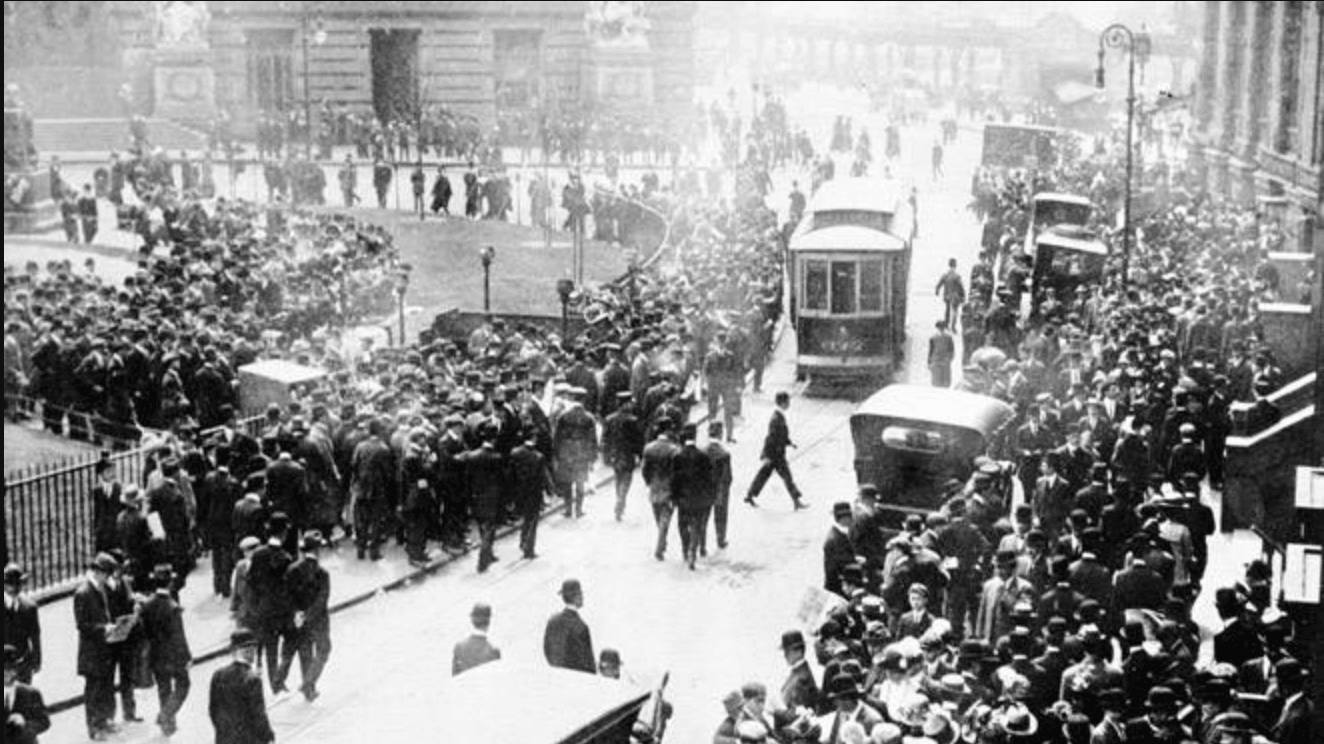

The ships of the White Star line were built in Belfast’s famous Harland and Wolf shipyard including the ill-fated “Titanic,” whose sinking in 1912 caused panic in Irish New York. The White Star Line advertised its ships as “Irish Boats” in Irish weeklies. After news that “Titanic” had hit an iceberg, concerned family and friends gathered on the steps of the building waiting for news of the Irish passengers on the ship.

Panic outside the White Star Line offices after news of the sinking of the “Titanic” reached New York.

Cunard Building, 25 Broadway

Not far from the White Star Line was another steamship company with deep ties to Ireland, the Cunard lines, whose ships sailed out of Cobh, Co. Cork. Still visible on the side of the building is the coat of arms of Queenstown, Cobh’s name when it was under British rule. Six Irish agents booked Irish immigrants passage on Cunard ships. The still visible separate entrances for “First Class” and “Cabin Class” on the Battery Park side of the building remind us of the strict class separation that characterized sailing on the Cunard Lines.

The author would like to credit John Ridge and his article in the New York Irish History Roundtable Journal #30, “Irish Landmarks in Downtown New York.”