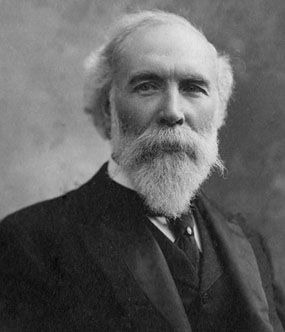

Down’s Hunter changed U.S. education

Today corporal punishment is not a part of most children’s education thanks in part to Irishman Thomas Hunter, but Hunter’s legacy goes even further. Currently, almost half the doctoral candidates in the United States are women, but before Hunter founded the college that would later bear his name, Manhattan’s Hunter College, few women in New York received higher education. Hunter’s many accomplishments include not only becoming the founder of the first free teachers college in the United States, but also the president of the first publicly supported American women’s college.

Hunter’s great success as an educator is even more amazing considering his humble origins. Born in Ardgrass, Co. Down in 1831, into a humble Church of Ireland family with Scottish ancestry, Hunter’s people on both sides of the family were sailors. His father, a sea captain, was a stern disciplinarian who instilled obedience with the rod. His mother passed away when Hunter was only 6 years old. Frequently at sea, Hunter’s father entrusted care of his son to aunts and uncles who scorned education. Thomas, though, became literate thanks to his maternal grandmother who taught him how to read through Bible readings.

Hunter despised the Irish educational system and his total contempt for the cruelty and stupidity of his teachers turned Hunter into an educational reformer determined to teach children humanely.

Hunter’s father remarried after the death of his mother and at age 12, he was sent off to an Episcopal parish school in Dundalk where bullying both by other students and savage beatings by the masters were routine. An extremely bright and sensitive child, Hunter held an innate belief in justice and railed against the many injustices committed in Irish schools. He developed a strong aversion to the brutal masters whom he described who sadistically flogged students. He later recalled that some of them were like demons and others half-idiots, yet despite the indiscriminate cruelty that was a hallmark of his schooling, the barbarities he endured never robbed Hunter of his sense of fairness and justice. Indeed, the brutality he and other boys endured only sharpened his outrage at the savagery of the schoolmasters. After being called impertinent by a teacher for insisting he had answered a question accurately, he defiantly said, "If it be impertinent to ask for justice, then I am impertinent."

Chosen to teach a class of children barely younger than he was, Hunter only used the rod as a last resort, while demonstrating an innate talent to teach. When students realized his aversion to physical punishment, they rebelled, challenging his authority and he reluctantly concluded that corporeal punishment was sometimes necessary. Hunter frequently stood up to bullies and by age sixteen he had grown strong enough both physically and mentally to deter any aggression. Boarding school was not only an education in letters, but more importantly, in the affairs of men, which helped the wily Hunter later in New York.

At age 15, Hunter won a competition to enter a school near Dublin where he proved himself highly proficient in math and drawing. While there, Hunter went to see the famous Daniel O’Connell speak in clear violation of school rules. Hunter claimed that his sympathy for the oppressed began in his boyhood when he heard. A huge throng had appeared to greet the beloved Catholic emancipator and an old woman gushed, “I’ve come down from the mountains and I’ve seen him, - glory be to god. I’ve seen the Liberator afore I die.” He credited O’Connell with awakening his empathy towards suffering people, stating, “I have always had the greatest sympathy for the oppressed races, the Poles, the Hungarians, the Irish and the Negroes.” Arriving in New York, he soon realized that free public education was the great stepping-stone for these downtrodden peoples to move upward.

Hunter’s innate sense of equity sensitized him to the great wrongs committed by British imperialism in Ireland. Despite his Protestant background, Hunter spoke out against these injustices, becoming a fervent patriot. Vociferously reading the writings of Irish Republicans, Hunter became an ardent believer in the Young Ireland movement and an advocate of physical-force Republicanism.

Hunter was hired as a teacher, but soon began to pen caustic anonymous articles for the Nation newspaper in favor of disestablishing the Church of Ireland. When his headmaster discovered his authorship of the articles, Hunter could no longer teach in Ireland and had to emigrate. The head constable of the police privately informed him that Dublin authorities were angered by his last letter in the Nation and were hungry for retribution.

In 1850, Hunter left for New York City. Arriving in New York with little money and no acquaintances, Hunter initially could not find work, but his belief in America’s republican government buoyed him. Hunter stated,” I loved it before I ever saw it. I became a citizen with all my heart and soul.” A man with a cosmopolitan worldview, Hunter was ideally suited to become a New Yorker teacher educating ethnic religious and socially diverse students.

Still bitter about his experiences in Irish schools, Hunter decided to give up teaching and start a new profession, but the only job he could find was teaching drawing. He was hired at Public School # 35 on Thirteenth Street, a school he later made famous. Hunter had an innate of sympathy for children stating, “I liked the boys and they liked me.” Given an art class, he soon proved himself a gifted educator who could control a large class, even though he was just nineteen years old.

Hunter differed from other teachers in one respect. He loathed beating his students, even when they misbehaved. Hunter’s dislike of corporeal punishment was not only considered highly unusual, but it was even regarded by some as a mark against him. The boys in the school, though quickly grew to love him and excelled under his tutelage.

Hunter wanted to become a principal because teaching was poorly paid and not esteemed. By 1857, when a vacancy for the principal of Public School # 35 emerged, Hunter had proven himself to be a superior classroom teacher, but his foreign birth was held against him. Many of the committee members on the principal selection committee were xenophobic Know-Nothings, fiercely opposed to a foreign-born principal. Additionally, many of these Know-Nothings mistakenly believed that Hunter was a Catholic, another mark against him. A man of Republican principles, Hunter believed he should not have to announce his religion to secure a job for which he was eminently qualified. Hunter despised the Know-Nothings and their bigotry, regarding it as un-American, but he knew that these xenophobes could also block his becoming principal.

Extremely affable, Hunter made friends easily and he had a politician’s knack for collecting favors. He soon turned the board in his favor and used political connections to force the Know-Nothings to vote against their prejudices for his candidacy. Shockingly, he was elected unanimously. The following year the Know-Nothings succeeded in removing all the other foreign-born principals, but the wily Hunter survived.

When Hunter became principal, he inherited a rattan cane for corporal punishment, but the cane brought back horrible personal memories. He abolished corporeal punishment at Public School #35, making it the first school not to beat students. His opponents predicted that scholarship and discipline would suffer. Despite predictions of disaster, the level of scholarship remained high and the school became extremely popular. Thanks to Hunter’s example, New York City became one of the first American school systems to abolish corporeal punishment and Hunter’s system of non-violent punishments was eventually adopted throughout the country.

A man of great ambition, Hunter was not content to remain principal. In 1866, he was elected Assistant Superintendent of Schools. Another man might have waited to become Superintendent of Schools, but Hunter moved in a riskier direction, taking a headmaster’s position in a newly formed all female school, while becoming an advocate for the higher education of women, a radical idea in the late 1860s. Until the latter part of 19th century, New York City had no free academy for girls above age 12, but in 1869, the city created the "Normal School" that later became Hunter College became the first publicly financed high school intended exclusively to train women in the art of teaching, but many chauvinists still felt that it was wrong to use public funds to educate women.

Hunter became a powerful advocate for female teachers. The Normal School’s first classes were held on February 14, 1870, with 700 women in its student body. It became the first free college in America possessing the power to grant degrees. Graduates were to be entrusted with the education of the future and were expected to uphold the highest moral and ethical standards. The school only admitted single women at first, believing married women should leave teaching to concentrate on their duties as wives and mothers.

Although he was first only recruited to help establish the new normal school, Hunter eventually became its principal. setting the educational standards, as well as the teaching methods. Hunter believed that the best teachers were well-read and excellent writers, ensuring that the courses taught in the Normal College were rigorous and that the students who entered the school were academically capable. Applicants were carefully screened.

During Hunter’s more than three-decade long tenure as president of the college, the school became known for its impartiality regarding race, religion, ethnicity and social class; its relentless pursuit of higher educational opportunities for women; its selective entry requirements; and its rigorous academics. The school’s population grew, as did its reputation for excellence. Hunter retired his presidency in 1906 and passed away in 1915.

His funeral service at the cathedral of Saint John the Divine filled the huge building. His pallbearers included all the state’s most important educational officials. He was eulogized for his more than six decades of service to public education that profoundly transformed New York. Generations of accomplished women owe their education to his unwavering belief in female education.