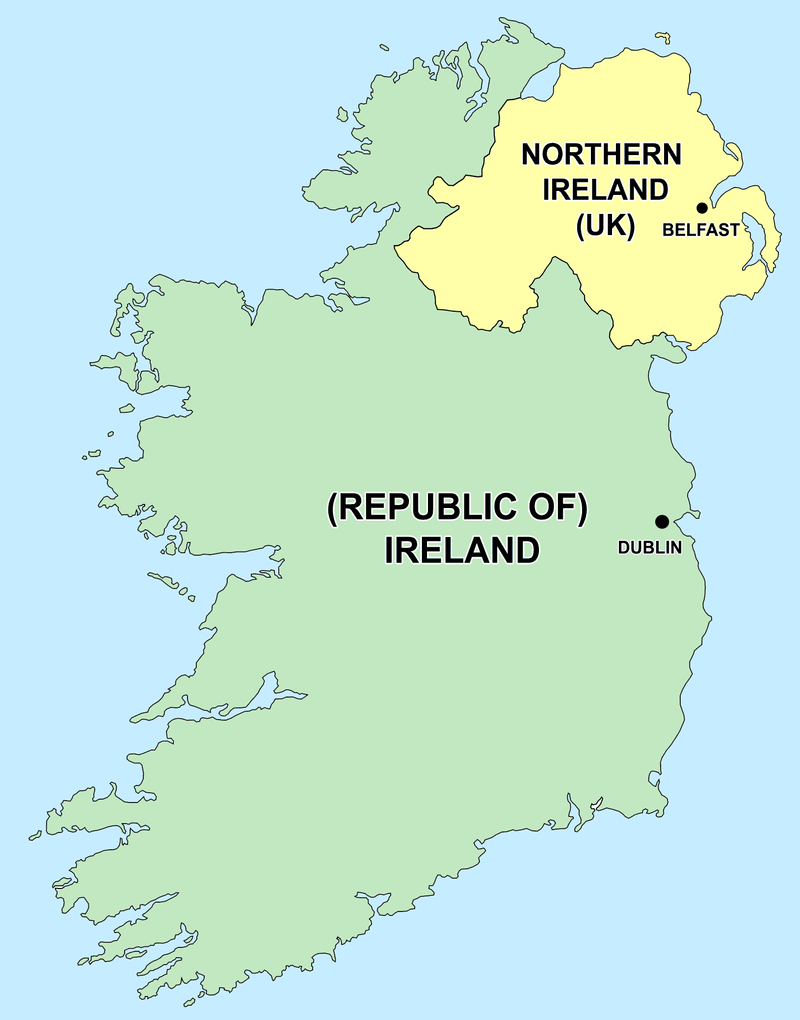

A few months ago, my son-in-law, Jimmy Frawley, who lives in Dublin, brought two of his children, aged 10 and 15, on a weekend trip to Belfast. He wanted them to become acquainted with a part of the island that they had never visited and knew little about.

Jimmy had read positive comments about the tours provided by the Black Taxi service, and, on arrival, he engaged one at the train station to provide a trip around Belfast.

They were lucky to get a talkative and knowledgeable guide who showed the main sites of interest with stops at murals and drawings representing the culture of both traditions in the divided city. His script was balanced and fair. However, towards the end of the hour-long tour he mentioned that his brother and uncle were shot at by Republicans back in the troubled 1980s.

Coming to the end, my son-in-law asked him whether he thought that a United Ireland would happen after the border poll promised in the Good Friday Agreement. He answered by pointing at my grandson’s dental braces and asking what they cost. He didn’t elaborate any further because, of course, such work would be completely free under the British National Health Service.

His point was well-taken. Why would families with a highly-rated, free hospital and doctor service opt for the chaotic system, plagued by waiting lists, currently operating in Dublin? The leaders in the South face a major challenge in introducing Slaintecare, a commendable healthcare policy which has the support of all the political parties, but is replete with knotty implementation issues.

A hundred years ago, during the years of the nationalist revolution and when the country was partitioned, Belfast and surrounding areas were flourishing economically. Shipbuilding in Belfast was in its pomp, and while the linen industry had declined in the 19th century it was rejuvenated during the Great War years with strong demand for material for uniforms and parachute covers.

By comparison, businesses in Dublin and other southern cities had to deal with poor demand with consequent low wages and extensive poverty. Many loyalists in the North ascribed their own economic success to a superior Protestant work ethic compared to the Catholic culture, which they associated with laziness and a propensity for frequenting the public house.

Those are sentiments that are rarely heard today. The economy in the South is booming since the Celtic Tiger arrived in the 1990s with Dublin now viewed as one of the busiest and most industrious cities in Europe. By comparison, economic activity in the North is lethargic with the local coffers in Stormont very dependent on big subsidies from Westminster.

The late historian, Andrew Boyd, wrote in his 1969 book "Holy War in Belfast" about “the fetishes that pass for politics” in a statelet founded on sectarian division. Brexit has accentuated these divisions. In the British referendum in 2016 the people in Northern Ireland, with overwhelming support in the Catholic community, voted strongly for the status quo, to remain in Europe.

However, a majority of unionists responded positively to the Tory clarion call of old-time English nationalism with its glorification of past imperial achievements. In addition, they barely hid their resentment that Germany, a country they defeated in two world wars, had passed them by and is now cock-a-hoop as the economic powerhouse of the European Union. They wanted out of that club which, in their view, London mistakenly joined in 1973.

The Brexit negotiators, following the vote to leave Europe, devised the protocol to avoid a hard border in Ireland which all parties agreed was crucial to prevent a return to the horrors of the Troubles. This arrangement gives Northern Ireland a foot in both Brussels and London, but unionists see the EU customs regulations governing Northern Ireland as a barrier between their territory and the rest of the United Kingdom, setting them apart from the English, Scots and Welsh.

Jeffrey Donaldson, the leader of the hardline Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), is adamant that Northern Ireland must be treated the same as other parts of the UK, but his political predicament was graphically described recently as like “a mouse dodging under the feet of two elephants.”

The likely result of ongoing negotiations between the British Government and the European Union will accommodate changes to the protocol but will not end the core mandate of a customs border on the Irish Sea.

Although somewhat less dominant than in past times, the constitutional issue still remains a focal point of politics in Northern Ireland, and the Brexit imbroglio emphasizes the deep divisions that still permeate the province. Studies show that the result of a border poll would likely be close and hard to predict.

Nationalists, thinking that they are close to their goal of a united Ireland, are in a magnanimous mood as they try to reassure loyalists that their distinct culture, including their allegiance to the Crown, would be respected in any new arrangement. Mary Lou McDonald, the Sinn Fein leader, offered that in a new Ireland she would favor making July 12th, Orangemen’s marching day, a national holiday.

Irish Prime Minister, Micheal Martin, has set up a government group to explore what he calls “an agreed Ireland.” All these laudatory efforts to consult and find common ground tumble on the cold fact that very few loyalists are interested in having the discussion. “Not an inch” still defines the outlook of a clear majority of unionists to any negotiation about the 1920 Act which divided the island.

Lord Ashcroft, a respected pollster, found two years ago that a razor-thin majority (51%) favored unification. That was the first major gauge of popular opinion pointing in that direction. Another Ashcroft poll published last month revealed a clear change in preference which is heartening for unionists. Excluding undecideds, 54% of citizens in the North want to continue under British rule with 46% opting for Irish unity.

Most of the responders explained that if a border poll is held in the near future, it would result in a continuation of the status quo. However, surprisingly, only one in three expect that same result if a referendum takes place in 2031. Ashcroft’s research indicates that seven out of ten voters under the age of twenty-five would vote for Irish unity. The Westminster connection is living on borrowed time.

The constitutional issue remains important to nationalists and unionists, but so does the strong desire of many younger members of both traditions that children should grow up in a community that isn’t shackled by old divisions and grievances.

The European subvention that greatly benefited Northern Ireland has dried up with predictably negative consequences, especially in the agricultural area. However, many businesses in the North have benefited from the easy access to markets in the Republic provided by the new customs arrangements. North/ South trade has increased by close to 40% since the protocol was introduced.

Economic considerations will be to the fore when the promised border poll is held. In this context, the Black Taxi driver identified a major obstacle to Irish unity, the quality of the health services in a united Ireland. The implementation of Slaintecare will be closely watched over the next few years.

Gerry O'Shea blogs at wemustbetalking.com