When Donegal man Patrick O’Donnell said a final goodbye to his wife Maggie in Philadelphia in May 1883 little could he have thought that within a very short period of time he would be the center of a major international media story of murder mystery, courtroom drama and political intrigue which would draw the attention of millions, including the U.S. president, Britain’s Queen Victoria and the French writer Victor Hugo.

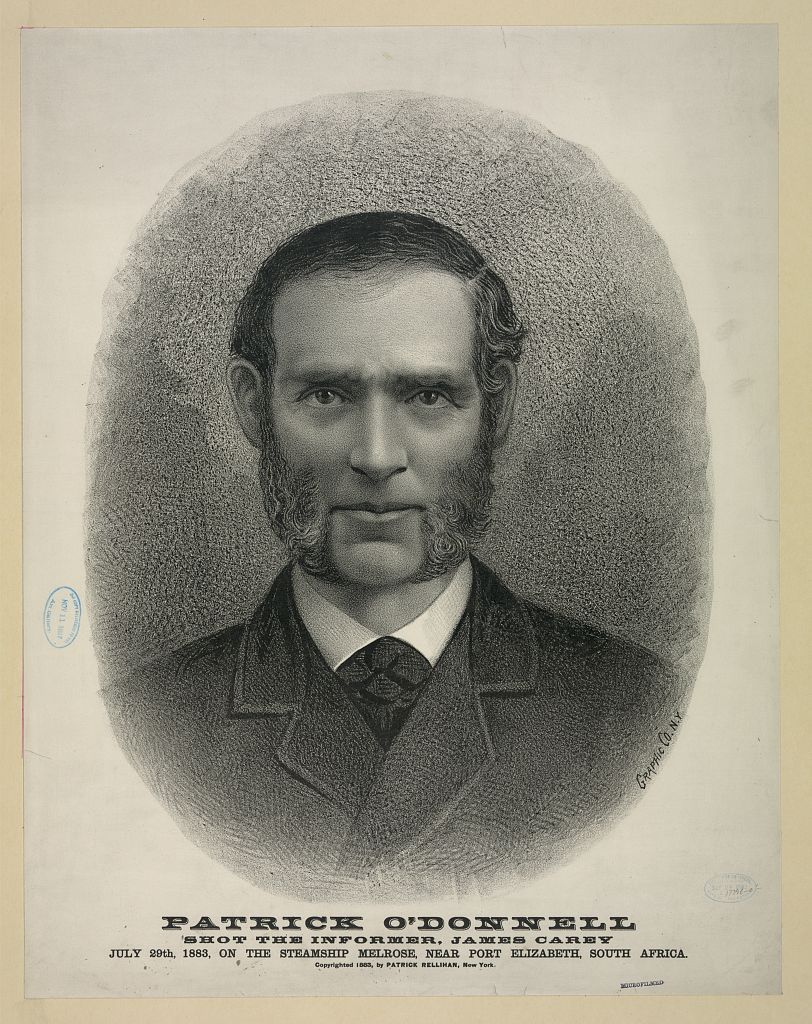

The quiet-spoken, six-foot tall O’Donnell was born 45 years earlier in Gweedore, a Gaeltacht or Irish-speaking area in the north-west of Ireland and although fluent in both Irish and English, he was illiterate in both languages, never having had the benefit of any kind of formal education.

He had spent four periods of time totaling over 20 years in the U.S. but had confided to friends that he believed that America was “played out” and, attracted by recent news of the riches available there, he was set on making his fortune in the diamond mines of South Africa.

In reality, he was walking from a failed marriage and the back-breaking toil of an impoverished laborer into an extraordinary adventure that would see his name etched in Irish history and immortalized for generations in ballads and on monuments in his native land.

A short break to visit his relatives in Donegal and the boat from Derry to Liverpool were the first steps on his journey to the new world and a new life. But Patrick O’Donnell was not alone on this trip. He was accompanied by a young woman, more than 20 years his junior, whom he met in Derry as he arranged his foreign travel. Susan Gallagher was also from Gweedore but was unhappy in her work “in service” to a noblewoman in Derry when O’Donnell proposed to her that she should accompany him on his journey to Cape Town and that they would marry at the first available opportunity, an unorthodox suggestion since he was already wed. She readily agreed and the couple travelled as Mr and Mrs O’Donnell.

During the three week, 7,200 nautical mile journey on board the “SS Kinfauns Castle” the O’Donnells became very friendly with another Irish couple Maggie and James Power who, with their seven children, were also heading off to a new life, in Durban on the Indian Ocean coast of South Africa. The two men became so friendly that Power convinced O’Donnell to abandon his plan to seek his fortune in the diamond mines but instead to continue the journey with him to Durban. Susan and Patrick O’Donnell eventually capitulated and having arrived in Cape Town agreed to leave again with the Power family on the “SS Melrose” to Durban.

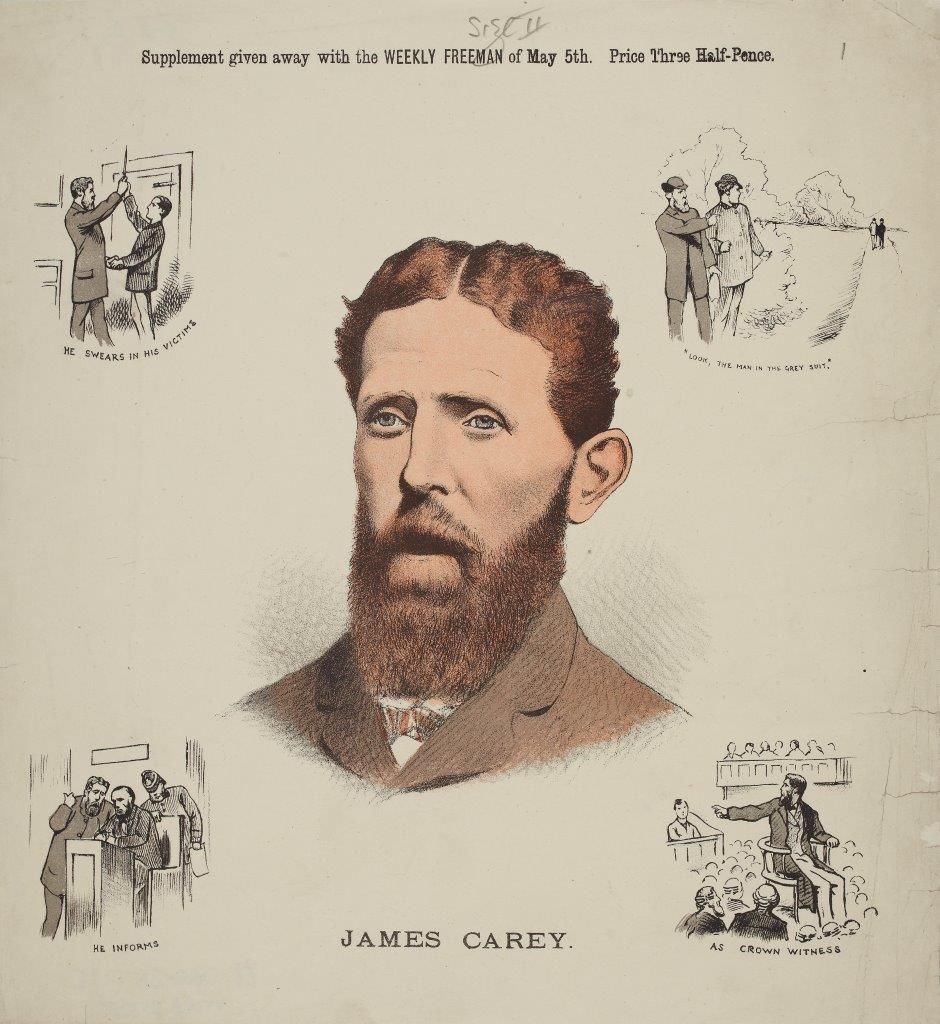

James Carey was a leading member of the Invincibles, but he turned informer on his comrades.

Before their departure, when James Power became involved in a squabble in Cape Town pub, a sharp-eyed barman recalled something familiar about him. He retrieved an old Irish newspaper and clearly identified James Power from a sketch there as being none other than James Carey, the most infamous informer in Irish history.

Carey had led the Fenian assassin squad known as the Invincibles who viciously stabbed and killed two of the most prominent members of Irish society at the time, the most senior civil servant in the country, Thomas Burke, and the chief secretary, Lord Cavendish. The killing, which became known as the Phoenix Park murders, sent shockwaves through the establishment and unleashed a wave of terror and fear in both royal and political circles.

But worse was to come. When James Carey was arrested he became an informer against his colleagues and gave evidence which saw five of them hang and 10 more imprisoned. This act of treachery earned him the hatred and loathing of most of the Irish population but his reward from the authorities was to be send off with his family to a new life in South Africa.

When Patrick O’Donnell was shown the newspaper sketch of James Carey as he stood on the quayside in Cape Town about to board the steamship for Durban he too immediately recognized the image as that of his “new best friend” of recent weeks, James Power. He was shocked to the core and exclaimed “I’ll shoot him!”

This was precisely what he did the very next day when he confronted Carey and accused him of being the treacherous informer despised throughout the length and breadth of Ireland. The altercation between the two men, in front of witnesses, lasted only a matter of minutes in the ship’s saloon. O’Donnell claimed that he shot Carey in self-defense as he believed his own life was in mortal danger from the former Invincibles’ leader. O’Donnell fired three shots in all from a pistol he had become accustomed to carry during his time in some of the wilder parts of the U.S. in the period around the American Civil War.

Patrick O’Donnell was immediately brought ashore in nearby Port Elizabeth where he was charged with murder. The British authorities ordered his extradition to the UK as they feared that the local colonial government might not be minded to convict a man for killing an informer.

A memorial to Patrick O’Donnell in Gweedore, Co. Donegal.

O’Donnell’s eventual trial in the Old Bailey in London was a sensational affair which attracted worldwide media attention. His conviction was secured after a short trial. Since he had been granted American citizenship during his years there the U.S. president sought to have his hanging postponed in hope of a successful appeal. The French luminary Victor Hugo telegraphed Queen Victoria to plead for his life, but to no avail.

His execution by a British hangman made Patrick O’Donnell a national hero in Ireland commemorated in numerous ballads and on large Celtic crosses in his native Gweedore and in Dublin.

In researching Patrick O’Donnell’s case for my new book and feature-length drama documentary — both entitled “The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell” — I came across what can only be described as shocking new evidence which clearly suggest that his conviction was a miscarriage of justice. A file form the British Home Office (equivalent of the U.S. Justice Department) sealed from public view for over 100 years reveals that Mr Justice Denman, who heard the case, withheld crucial information from O’Donnell’s defense team, the press and the court in general.

He withheld the information that the jury believed the shooting of Carey was “without malice aforethought.” A killing without malice would have equated to manslaughter punishable then by a short prison sentence as opposed to the mandatory hanging which accompanied conviction for murder with malice aforethought.

For Patrick O’Donnell the judges’ deception was a matter of life or death.

[Seán Ó Cuirreáin, a former journalist and broadcaster, is author of “The Queen v Patrick O’Donnell,” published by Four Courts Press, and executive producer of the drama-documentary of the same title for the Irish TV service TG4. The book is now available via the usual booksellers or directly from the publishers and the film is scheduled for transmission in early 2022.]