"Eoin Ua Cathail was a fabulist and a memoirist who wrote stories in Irish about the American West and Midwest. He was a master of detail and chronicler of the impossible, the outlandish, and the improbable. His own life provided the inspiration for his work, and he claimed that his stories were true, but I am very sure that none of these stories happened as he tells them, and most of them probably never happened at all."

So writes Professor Richard White of Stanford University in the foreword to Patrick J. Mahoney's "Recovering an Irish Voice from the American Frontier: The Prose Writings of Eoin Ua Cathail."

In those writings, White says, the Irish prosper in the U.S. not through the generosity of Americans "but through their courage, wit, generosity, cunning, and loyalty to each other."

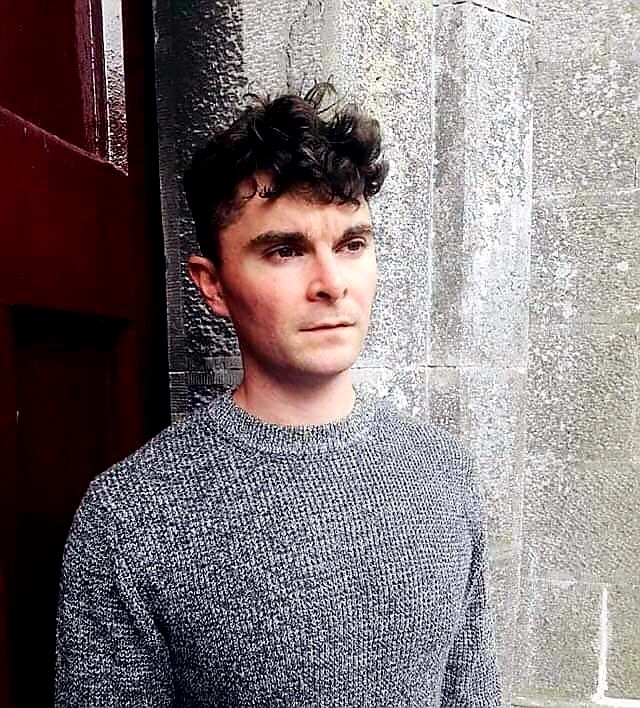

The Echo asked Mahoney, who is Casperan Fellow in History and Culture at Drew University and a Fulbright Scholar at the National University of Ireland Galway, some questions about Ua Cathail and the process of doing the book.

What sparked your interest in Eoin Ua Cathail?

I initially became interested in the story of Eoin Ua Cathail after seeing a reference to his poetry by the late scholar Kenneth Nielsen. In discussing U.S-based Irish language writers, Nielsen passingly mentioned one who had attempted to blend the themes of Irish mythology and American dime novels in Ossianic style verse. I immediately knew I had to learn more about this mysterious Gaelic poet of the plains. I saw that some of his papers were held in the archives at the National University of Ireland Galway, so I started there.

In the end, I was drawn in by the complex and often problematic views expressed within his prose works, rather than his poetry. From unabashed support for Native American displacement and later American imperialism to wistful reflections about the effects of deforestation and industry, Ua Cathail’s writings offer fascinating insights into the 19th-century Irish-American experience.

How do his writings differ from other contemporary works?

Well for one, he was writing almost exclusively in Irish. Despite the droves of Irish speakers who relocated to the United States during the mid to late 19th century, very few left accounts in their native tongue. One of the few exceptions was Micí Mac Gabhann, who travelled from Donegal to the American West to make his fortune around the turn of the twentieth century. His memoir, "Rotha Mór an tSaoil" (translated as the "Hard Road to Klondike" in 1962) describes his journey from Ireland to the gold fields of the Klondike and just about everywhere in between.

That being said, his writings differ from Ua Cathail’s in a number of important ways. Mac Gabhann’s recollections weren’t actually written down in standard fashion. He recited his stories to his son-in-law, the renowned folklorist, Seán Ó hEochaidh, who then put them to paper. Meanwhile, Ua Cathail physically wrote his own manuscripts and sent them to various individuals who he thought might be interested (most notably Gaelic League founder and later first president of Ireland, Douglas Hyde). Moreover, while Mac Gabhann delivered fairly straight-forward reflections of his time in the U.S., Ua Cathail was experimenting with different literary forms to craft semi-autobiographical tales equally rooted in the experiences and folk traditions of the New and Old Worlds.

How were you able to tackle the original Irish?

Ua Cathail’s Irish is quite unique. He grew up in an area of West Limerick where the language was already in steep decline by the mid-19th century. By his own account, he only came to really appreciate its importance after he emigrated in 1863. It was amidst the multilingual landscape of the United States that he honed his command of Irish, learning along the way from fellow immigrants.

Linguistically, the modern reader will immediately notice a number of peculiarities in his stories, ranging from outdated spellings and dialect-specific terms and phrasing, to instances where Ua Cathail creatively adapted the language to suit his surroundings. This is not an uncommon trait amongst Irish language writers of the time, as they were writing before any sort of standardization. To keep things consistent as I worked my way through the stories, I made a running list of what I quickly began to call “Ua Cathail-isms”. This helped me to decipher and map out which anomalies he used regularly throughout and then keep them as they were as I began editing the text.

My own background with the language was obviously a major factor in taking on and being able to manage the project as well. Believe it or not I learned my Irish from a former “blanket man” (who had participated in the protest for prisoners’ rights in the H-Blocks between 1976–81). During my college years, he gave me a job as a painter and provided me daily lessons in the language. I’ve since gone on to do a higher diploma in Irish at the Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge in Galway, which allowed me to broaden my knowledge of the other dialects and fine-tune my grammar.

What was your translation approach?

In carrying out the translation, my guiding aim was to stay as true to the original as possible while also presenting an accessible and appealing text for English language readers. As part of this process, I read a considerable amount of "Frontier" memoirs and Dime Novel literature published around the same time as Ua Cathail’s works. This allowed me to develop a familiarity with the sort of phrasing and word choices that his English language contemporaries used to describe the same subjects, landscapes and situations.

The collection is published with facing Irish-English pages, so some of my linguistic decisions will be fairly obvious to bilingual readers. For example, my rendering of "naomhóg" as "canoe" instead of its more traditional Munster usage as a "curragh," or "tuaghanna" as "tomahawks" instead of "axes." There were also a number of more subtle decisions that I made to improve the flow and readability of the stories from their original manuscript forms.

What was your favorite part of the project?

I have to say I really enjoyed just constantly learning more about Ua Cathail and trying to decipher how closely his life experiences resembled what he depicted in his stories. Like Buffalo Bill Cody and other folk heroes of the American West, Ua Cathail seamlessly blended fact and fiction in his recollections – peppering the banality of everyday life with incredible feats, daring escapes and exaggerated claims. While as a historian this could be frustrating at times, I think I succeeded in providing readers with a good picture of the man, the character, and more importantly, where the two converge.

What was your most interesting discovery?

I think the most interesting discovery came whilst going through a private letter that Ua Cathail wrote to one of his nieces, the well-known actress and playwright, Florence Johns. At one point in which he broached the topic of organized religion, I immediately noticed that the language and phrasing was out of place with his usual flow and authorial voice. After what seemed like an eternity of sifting through databases to see if he had borrowed it from somewhere, I found the passage printed verbatim in the text of a popular adventure writer and historian, James W. Buel. I ended up reading a number of Buel’s other works written around that time, and in doing so, noted a few other instances that seemingly inspired the plots of Ua Cathail’s Irish language stories.

How did the pandemic impact your ability to get the book done?

When the pandemic first struck, I feared that the whole project might go by the wayside as access to both the National Library of Ireland and the Galway archives suddenly ground to a halt. Luckily, I had already transcribed a majority of the stories by that stage. While I still ran into a few logistical problems in the months to come, the pandemic was actually a blessing in disguise. Being so isolated during the first few months, I had a lot more time to devote to finishing the translation and carrying out the necessary background research. I was also probably more apt than ever to reach out and connect with different people about the project. I was so heartened by the help and advice I received from so many during that time, and looking back, it really made the final product all the more special.