Young men registering for military conscription, New York City, June 5, 1917.

By Geoffrey Cobb

I have lived in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, for decades, yet somehow I was oblivious to the fact that McCarren park has a Nulty Square. Knowing that Nulty was an Irish name, I became curious about the person’s identity and uncovered a long forgotten story of two Irish-American heroes and their grieving mother.

I found out pretty quickly that T. Raymond Nulty was a fallen soldier in World War I, but I decided to dig deeper through archived editions of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and slowly I was able to piece the story together. Mary Nulty was a Greenpoint mother of six children, three boys and three girls. Her second son, Thomas Raymond, but called T. Raymond to avoid confusing him with his father. His name appeared three times in the paper.

Young Thomas Nulty was a standout student at Saint Anthony of Padua school in Greenpoint. T. Raymond Nulty’s name comes up reciting a poem in an event at Holy Family Church, receiving honors for an oratory contest and playing a role in the school’s drama club.

When America entered the world war, all three of the Nulty boys enlisted. Thomas Raymond and his brother John joined the famous “Fighting 69th Regiment. The Nulty boys were exactly what regiment organizers William “Wild Bill” Donovan and Fr. Francis Duffy were looking for. Though the “Fighting 69th became legendary for its Civil War heroism, in some circles of the American military the Irish regiment had a dubious reputation for brawling and drinking. Donovan and Duffy decided to create an elite unit and choose the flower of New York Irish American youth- clean cut, athletic and intelligent men from good families. The Regiment would again demonstrate legendary valor in battle, while taking huge casualties and later become the subject of a hit Hollywood film.

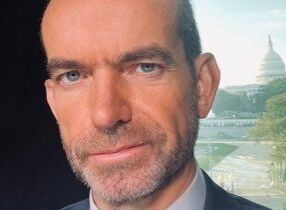

Lt. Col. William “Wild Bill” Donovan on Sept. 6, 1918.

Thomas arrived along with the other members of the 69th in December 1917 and served as a machine gunner. He must have been a good soldier because he was promoted from private to corporal.

In July 1918, the 69th was sent to the Marne to stop the German army from advancing to Paris, which they and other American forces did. On the night of July 26, German forces pulling back from the Marne Salient reached the River Ourcq. There, they formed a line on the River’s far bank, hoping to slow advancing American forces, while their comrades withdrew. Nulty’s 165th Infantry mistakenly believed the Germans to be in full retreat. When the New York soldiers crossed the river on July 28, they learned that the Germans hadn’t retreated and held a strong defensive position. The Germans had blown up two bridges over the Ourcq near Sergy; the stream was swollen with rains to a width of 14 meters and a depth of four, so crossing the river would be challenging. As they crossed the swollen river machine guns opened on the 69th from directly in front and from a farm on the flank as the Ourcq quickly ran red with the blood of the Americans.

The 165th Infantry crossed, fought heroically and established the first foothold on the eastern bank, but Corporal Nulty did not make it, dying on July 28, 1918. The young Irish-American corporal was buried along with tens of thousands of other soldiers in an American military cemetery in France. A soldier was dispatched to the Nulty home to give Mary and the family the grim news from France.

Nulty was one of a 108 young Greenpoint men who paid the ultimate price, but Nulty must have been someone special for those who returned from the war named the local chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars in his honor, but this was not the only grief that Mary Nulty would bear. His brother Edwin, who had served in another regiment, made it home, but he was sent to a veteran’s hospital stateside and died suffering with every breath he drew, a victim of poison gas. He told his mother that he wished he had died like his brother in combat. Only the oldest brother John Nulty remained alive.

Corporal Thomas Raymond Nulty was one of three brothers who enlisted to fight in World War I.

Mary Nulty founded a gold medal at Saint Anthony of Padua in T. Raymond’s name and she became part of a massive local movement to honor the dead with a war memorial, which still stands in McGolrick Park. On May 23, 1923, Mary was one of 97 Gold Star mothers who were present at the unveiling of a beautiful World War I memorial sculpture, a bronze winged victory by German sculptor Carl Augustus Heber. The statue depicts a female allegorical figure, holding aloft a modified laurel, symbol of victory, and in her right hand supporting a large palm frond, symbol of peace. The granite pedestal is inscribed with the names of battle sites in France. Three hundred uniformed veterans sang America as the VFW Chapter named for her son stood at attention dressed in their military uniforms.

Later that year, they dedicated Nulty Square in McCarren Park. Oct. 26, 1923. Mary was asked to pull off the American flag covering a battle scarred 105 millimeter German gun that was unveiled next to a memorial flagpole in front of the Second Battalion of the 69th Regiment. Taps were played and a volley was fired by the Nulty post.

Twelve years later, Mary Nulty was featured in an article about Brooklyn Gold Star mothers who had never been to France to see the graves of their fallen sons, in which she said, “ It’s not nice to think about a son buried somewhere in France.” The article announced that the government would fund the journey to the military cemeteries in France where Mary’s son, and so many other Americans, lay. I hope that traveling to France and praying by her young son’s graveside brought Mary some peace.

Her only surviving son Joe died nine years later at age 43. Sadly, Mary lived long enough to bury the three boys she had sent off to the war to end all wars. Now, I will never walk by Nulty Square and not think about the Nulty family who suffered so much for America.