The attack on Pearl Harbor, an event that changed the course of world history, took place eighty years ago today.

What makes Pearl Harbor so different from other American fields of battle is that, well, for starters it’s not a field.

But it’s not just to do with the fact that the pivotal center of the Japanese attack eight decades ago was an expanse of water, but also what that water contains.

Water as the covering for a grave lacks that sense of firm finality that earth conveys.

And this sense is heightened by the fact that the most hallowed of the graves in Pearl Harbor, - that of those who died aboard the battleship Arizona – is in shallow water, and that the ship can still be seen in certain conditions.

More than this, the Arizona still leaks oil as this writer witnessed on two visits to Pearl Harbor, one back in the 1990s, the second in 2008.

And the leaking continues into present time at a rate of between two and nine quarts per day depending on conditions.

This, then, is a battle site where the effects of the battle have not subsided with time.

This, too, is also the case of the images and memories from December 7th, 1941, that date destined to live in infamy.

2,403 Americans died that day. More than a thousand others were wounded.

Not a few of the dead were Irish Americans.

Two Irish Americans secured the very opposite of infamy by winning the Congressional Medal of Honor.

They were John William Finn, who survived the attack, and Frank C. Flaherty who did not.

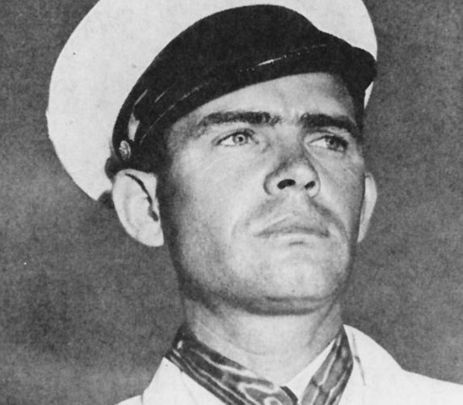

Finn, a chief aviation ordnance man stationed at Naval Air Station Kaneohe Bay, earned his medal by manning a machine gun from an exposed position throughout the attack, despite being repeatedly wounded.

Like just about everyone else on Oahu that day, Finn was rousted from the relatively somnolent duties of a Sunday morning.

Finn didn’t hesitate.

He ran to a mounted gun and began firing at enemy aircraft. Two hours later he had twenty-one shrapnel wounds and a record of heroic action that would earn him the first Medal of Honor for World War II.

Born in 1909, Finn would live to be a hundred. He died in May, 2010.

He was born on July 24, 1909 in Los Angeles. His grandparents on his father’s side were immigrants from County Galway.

His father supported the family as a shipping clerk in a machinery firm and later as a plumber. Young John left school at age eleven to work. In 1926, at the age of seventeen, he enlisted in the Navy.

He looked so young that his mother had to accompany him to the recruiting station to verify his age. Finn’s lack of formal education didn’t hold him back in the Navy and by 1935 he had risen to the rank of chief petty officer. Six years later, in December 1941, he found himself stationed at Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii as Navy aviation chief ordnance officer.

The attack on Pearl Harbor and other military facilities on Oahu commenced a few minutes before 8 a.m. and caught American forces completely by surprise.

The Pacific fleet was a sitting duck and the Japanese pilots took full advantage. Those Americans, who could, eventually fought back. When John Finn reached his base it was too late to launch any Navy pilots (their planes were in flames), so he ran to a mounted .50 caliber machine gun and began firing.

His position was completely exposed and soon came under fire. Despite numerous shrapnel wounds, Finn kept up the fight. “I just kept shooting,” he later said in an interview, “because I wasn’t dead.”

Witnesses later claimed that he shot down at least one Japanese plane.

“I’m not sure I shot a plane down, but I can take credit for shooting at every plane I could bear on.”

Two hours later, Finn was receiving medical treatment for twenty-one shrapnel wounds and learning the dreadful details of the attack.

Eighteen ships, including all eight battleships of the Pacific fleet, were sunk or badly damaged. Over 350 aircraft, most while still on the ground, had been destroyed.

Nine months later, Finn (now an Ensign) received the Medal of Honor aboard the USS Enterprise from Admiral Chester Nimitz.

The official citation bears reading in full: “For extraordinary heroism distinguished service, and devotion above and beyond the call of duty. During the first attack by Japanese airplanes on the Naval Air Station, Kaneohe Bay, on December 7, 1941, Lt. Finn promptly secured and manned a .50-caliber machinegun mounted on an instruction stand in a completely exposed section of the parking ramp, which was under heavy enemy machine gun strafing fire. Although painfully wounded many times, he continued to man this gun and to return the enemy’s fire vigorously and with telling effect throughout the enemy strafing and bombing attacks and with complete disregard for his own personal safety. It was only by specific orders that he was persuaded to leave his post to seek medical attention. Following first aid treatment, although obviously suffering much pain and moving with great difficulty, he returned to the squadron area and actively supervised the rearming of returning planes. His extraordinary heroism and conduct in this action were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.”

Finn remained in the Navy for the duration of the war and stayed on after 1947 in the Navy reserves. He retired in 1956 (at 47 years of age) with the rank of Lieutenant.

He spent the next few decades running a repair shop in San Diego and then a 92-acre ranch 70 miles outside San Diego that he and his wife, Alice, bought in the late 1950s.

Intensely patriotic, and proud of his Irish heritage, he attended World War II memorial services and served for many years as a spokesman for causes such as the campaign to raise funds to secure and preserve the USS Arizona memorial.

While John Finn faced the enemy and survived that day, so long ago and yet so vivid, Frank Flaherty did not live.

And his bravery was not displayed by hands on a machine gun, but rather a flashlight.

There were many acts of extraordinary heroism at Pearl Harbor and they were performed in myriad ways.

Flaherty, who was from Charlotte, Michigan, and an Ensign at the time of the attack, was aboard the USS Oklahoma.

Flaherty’s Medal of Honor reads in part: For extraordinary devotion to duty and extraordinary courage and complete disregard of his own life….when it was seen the USS Oklahoma was going to capsize and the order was given to abandon ship, Ensign Flaherty remained in the turret, holding a flashlight so the remainder of the turret crew could see to escape, thereby sacrificing his own life.”

429 men were entombed in the Oklahoma at Pearl Harbor, including Flaherty, after the great ship rolled over.

The ship was raised for salvage in 1943, and the remains inside were eventually interred in mass graves marked "Unknowns" at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.

In 1943 a destroyer bearing Flaherty's name was commissioned and it served for the duration of the war.

Flaherty's name is inscribed in the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, and a memorial headstone was placed in Maple Hill Cemetery in his Michigan hometown.

Along with all the other heroes of December 7, 1941, he will be especially remembered on this, the 80th anniversary.

* This is a revised version of a story for published in 2016 to mark the 75th anniversary.