A commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Death of James McNally Wilson, one of the Catalpa Six, is set for this Saturday, November 6 at 1 p.m. in Saint Mary’s Cemetery, 103 Pine Street, Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

The commemoration will be followed by a celebration of the lives of Catalpa escapees James Wilson, Michael Harrington and Thomas Hassett at 2 p.m. in the nearby Galway Bay Pub.

Memorial pins are available for $15 or two for $25. For these and all other information Contact George McLaughlin at (401)688-2463 or fenianmca@gmail.com. Donations to www.fenianmca.org.

Checks should be made out to George McLaughlin accompanied by an on check memo of "Fenian Memorial Committee." Mail to: FMCA, P.O. Box 10416, Cranston, RI 02910.

All proceeds will go to the Fenian Memorial Committee for the purchase and erection of grave markers for Michael Harrington and Thomas Hassett in Calvary Cemetery, Queens, New York.

By way of background to Saturday’s gathering here is the remainder of the release from the organizers.

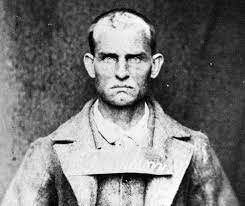

“What a death is staring us in the face,” wrote James Wilson in 1873, “the death of a felon in a British dungeon, and a grave amongst Britain’s ruffians. I am not ashamed to speak the truth, that it is a disgrace to have us in prison today.

“A little money judiciously expended would release every man that is now in West Australia. Think that we have been …in this living tomb since our first arrest, and that it is impossible for mind or body to withstand the continual strain that is upon us. One or the other must give way.” Fenian James Wilson, was imprisoned with other Irish political prisoners half a world away from the Irish-American recipients of his letter, in the dreaded Fremantle penal colony in Western Australia.

To underline this message Wilson added, “Remember this is a voice from the tomb. For is this not a living tomb? In the tomb it is only a man’s body that is good for worms, but in this living tomb the canker worm of care enters the very soul.”

Wilson’s powerful words moved Irish-Americans and they resolved to help him. In Ireland in the early 1860s Wilson had joined the 5th Dragoon (British Army) Guards. But in secret he also became a Fenian, taking an oath to be obedient to his leaders and to do his utmost to secure a democratic independent Irish Republic. To that end he deserted with fellow Fenian Martin Hogan in November 1865 after they had secretly enrolled many other Irish soldiers in the organization. But then, as so often in Irish history, local informers gave away the details of renewed Fenian activities to the British forces, and Wilson was quickly arrested.

Wilson and many comrades were court-martialed in Dublin on February 10, 1866, where they found guilty of mutinous conduct and received a sentence of death, which was later commuted to life imprisonment in the Australian Fremantle prison. It was, in a real sense, a kind of death in life.

After surveillance aid from members of the Clann na Gael and secret communications from the Irish born prison priest, Fr. Patrick McCabe, help finally arrived in the shape of the Catalpa, an American whaling ship hired by another Fenian, John Devoy, from secret donations made by Irish independence organizations across the United States. Amazingly, informers did not foil the daring rescue plan and the ship reached Australia without major mishap. The rescuers rowed to shore to collect the six waiting Irish convicts who had left their posts while working outside the secured area. Their Irish rescuers were waiting with wagons and weapons. But like all good rescue dramas, complications clouded their flight. When the freed prisoners began to row back to the Catalpa a sudden unexpected storm meant they could not reach the ship for another day, by which time the alarm had been raised and British police ships launched.

The British commandeered a gunboat, the Georgette, which they pulled alongside the Catalpa, requesting that the prisoners be handed over. Captain Anthony, the ship’s celebrated American captain, defiantly refused this request and raised the American flag, warning his pursuers that the Catalpa was in international waters and could not be boarded. If they fired on the Catalpa they would be firing on the United States.

Although enraged by this parry the Georgette’s British captain, reluctantly conceded. Eventually, the Georgette was forced to give up the chase, although all on board were convinced they had seen the missing men. Shortly after, as John Devoy, Fenian and organizer of the rescue predicted, the Catalpa rescue bolstered Irish resistance across the globe and spurred the fight for Irish independence, which was partially won in 1922.

None of the Catalpa Six ever returned to Ireland. All remained until their deaths, in America, including the two old comrades, James McNally Wilson who lived out his life in Central Falls and Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where he is buried, and Martin Hogan, who spent the remainder of his life in Chicago, Illinois and is buried there. Thomas Darragh and Robert Cranston, are both buried in Philadelphia. Father Patrick McCabe, who was instrumental in the Catalpa escape and eventually fled Australia for Minnesota, is buried there. Through the efforts of the Fenian Memorial Committee of America, memorial stones or grave markers have been erected for all these men. Two others are buried in Calvary Cemetery in New York: Thomas Hassett and Michael Harrington are still without tombstones. In James McNally Wilson’s name, we hope to raise sufficient funds to honor these brave men with their long overdue tombstones.